Getting serious

I occasionally get self-conscious about devoting a lot of my writing to what could be considered trashy, disposable movies. There’s a lot of genre and exploitation here on the blog. Although once or twice a month that’s offset thanks to the review copies I receive from Criterion which force me to write about something more serious, I have a bad habit of avoiding comment on movies which require a bit more thought – while I do enjoy watching and talking about these genre movies, I also spend time watching more cinematically demanding films which I ought to mention. My only excuse for continually putting them off is laziness. Although this post is not going to do them the justice they deserve, I will at least acknowledge a few of them this week … belatedly, as I watched most if them a couple of months ago.

*

Maigret

Already I’m fudging slightly by starting with a couple of genre films, though they are classy ones with subtitles. In the late 1950s Jean Delannoy adapted a couple of Georges Simenon’s novels with the great Jean Gabin playing Inspector Maigret. (Gabin made a third Maigret movie a few years later, though that was directed Gilles Grangier, a prolific director whose work I’m unfamiliar with.) Since I’ve been immersed in Maigret’s world for the past year, having watched all fifty-four feature-length episodes of the French television series starring Bruno Cremer and so far read twenty-seven of the novels and a collection of stories, I naturally had to buy Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray releases of Delannoy’s movies, Maigret Sets a Trap (1958) and Maigret and the St. Fiacre Case (1959).

There are two things which appeal to me about Simenon’s work. The first is the character of Maigret himself, a dogged, frequently grumpy and uncommunicative investigator who patiently waits for his cases to reveal themselves to him (often while sitting in cafes drinking copious amounts of beer and white wine). The second is the sense of place, the physical and social textures illuminated by the often pathetic and sordid details of the crimes he investigates. In Maigret Sets a Trap, someone is killing women on the streets of Montmartre and the Inspector makes a big deal of signalling to the press that the killer has been caught, although he hasn’t. He hopes that the publicity will provoke another attack and sends a number of policewomen into the streets as bait. As in quite a few of the stories, Maigret’s pursuit of a solution trumps any other concerns (it happens quite frequently that people die in the course of an investigation, at times as a direct result of Maigret’s decisions) and one of the decoys is attacked, though in this case she survives and manages to identify a suspect. With the man in custody, another murder occurs, complicating things.

The appeal of Maigret and the St. Fiacre Case is that it takes the Inspector back to his childhood home, a large estate where his father was manager for many years. The noble family is in decline, the old Countess selling off possessions in part to support her wastrel son’s life in the city. There are rumours that she is in a relationship with her secretary, a much younger man. Maigret is brought back because of an anonymous note sent to the police predicting a crime in the village church during first mass. It’s all a bit vague, and he sleeps in that morning, arriving late at the church to find the Countess dead of a sudden heart attack. He doesn’t believe it was natural causes and begins to dig into the family’s secrets as the community prepares for the funeral which essentially marks the end of the local aristocracy. While the son and the secretary seem to be the most likely suspects, the solution turns out to be rooted not only in greed but also class resentment.

Both films are shot in atmospheric black-and-white by Louis Page, the location work adding to their appeal with incidental glimpses of a France poised between a moribund past and the waves of change which would alter the social and political landscape in the next decade. Gabin anchors the mysteries with the weight of a presence rooted in three decades at the centre of French cinema, and the casts of both films are filled with excellent character actors. It’s a pity that Kino didn’t include any supplements as there would be a lot to say not only about these specific productions, but also about Simenon and his most famous creation.

*

Bacurau

(Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles, 2019)

I’m a bit ambivalent about Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles’s Bacurau (2019), a movie which blends genres in ways which I didn’t find entirely satisfying. This blend of western and post-apocalyptic dystopia set a few years in the future in a remote area of Brazil seems like a long way from Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds (2012), a brilliant, complex dissection of the social and psychological tolls inflicted on ordinary Brazilian lives by a corrupt economic system. But the long opening section of Bacurau reflects similar concerns, just displaced from an urban centre to a remote rural area.

A woman travels back to her village, where an elder lies dying. There are intimations of danger – out here lawlessness rules, with water controlled by private operators supported by corrupt politicians. A local bandit hero is hiding out nearby. The people of the village are fiercely independent and largely self-sufficient despite the political and criminal forces which apply constant pressure on the community. This is a carefully observed portrait of ordinary people resisting however they can the forces of multinational capitalism and its corrupt local servants.

Slowly, strange things begin to happen. A class at the local school discovers that the village has disappeared from Google Earth; cell phone reception fails; and a family living in a nearby farm are viciously murdered. Focus suddenly shifts away from the village to a group of heavily-armed people set up in an isolated compound with sophisticated surveillance and communications equipment. In charge is a German-accented man who has little patience for the petty conflicts running through the group, mostly young white men and women. Are these people mercenaries tasked with dealing with the local cartel? While we wait to find out what’s actually going on, we get to enjoy seeing none other than Udo Kier as their leader, Michael.

Up to this point, I was totally engaged; a small population dealing with their own personal conflicts being confronted by the larger forces of a global system which not only doesn’t care about their lives but even sees them as a nuisance getting in the way of corporate interests … this was shaping up to be a timely thriller. But then it shifts and, although the filmmaking remains polished and effective, I found myself losing interest. Something new was introduced into what was effectively a contemporary western. The bad guys threatening the townspeople turn out to be murder tourists, bored Americans and Europeans who have paid a large sum for the privilege of playing “the most dangerous game”. They are here to hunt and kill the inhabitants of a village which has already been digitally erased. In effect, Bacurau is high-class variation on Hostel.

There is generic satisfaction in watching the villagers use their native ingenuity to defend themselves from these hunters, but the overriding metaphor – for me anyway – is cheapened by shifting focus from the global economic system to a bunch of individual assholes looking for entertainment in others’ suffering. This shift is further confused by Michael, who once the attack on the village is underway, starts to kill his own customers rather than the villagers … something which is never clearly explained, other than by his obvious distaste for these scumbags.

There is much to like about Bacurau. The cast is excellent, particularly Barbara Colen, Thomas Aquino and Silvero Pereira as the default leaders of the defence, Sonia Braga as the local doctor, and of course Udo Kier. The landscapes provide a stunning backdrop to the violence; the ubiquitous presence of technology in this remote peasant community provides a disconcerting glimpse of how past, present and future are intertwined in startling ways even in this isolated place. Mendonça Filho and Dornelles capture the tension between the villagers’ languid pace of life and the abrupt eruptions of violence and there are sequences which build effective narrative suspense. Nonetheless, that shift from a clear-eyed political and economic analysis of global forces to a personalized depiction of Northern privilege shitting on the rest of the world somehow seems to minimize those larger issues.

Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray sports an excellent image and provides extensive features about the genesis and making of the film, including a feature-length documentary which shows the directors working with a largely non-professional local cast to create a convincing depiction of the community. There’s also a commentary by the directors, a discussion by the directors and Braga after a screening in New York, an interview with the two directors and a short film by Dornelles.

*

Ladybug Ladybug (Frank Perry, 1964)

Frank Perry was an interesting filmmaker whose career went in odd directions. His early work, beginning with David and Lisa (1963) and, arguably, peaking with his third feature, The Swimmer (1968), which was taken away from him and reworked by the producers with the “help” of an uncredited Sydney Pollack, was marked by something which has always been an uneasy fit with the Hollywood mainstream – a pronounced earnestness which sometimes makes you feel that Perry (and wife Eleanor Perry who wrote the scripts for his first six features) is revealing himself with a raw, unfiltered honesty which can be uncomfortable to watch. He did eventually move towards the mainstream, but with mixed results: Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970), ‘Doc’ (1971), Play It As It Lays (1972), Man on a Swing (1974), culminating in an excess of camp melodrama with Mommie Dearest (1981) and Monsignor (1982), movies which seem worlds away from his early attempts at stark realism.

Following the success of his debut feature, David and Lisa, a romance between mentally troubled teenagers which pretty much defines “sensitive”, the Perrys made a much less well-known movie which deals with children struggling to function in a world which threatens to destroy them. Made in the shadow of the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Ladybug Ladybug (1963) focuses on the staff and children at a small rural school as they deal with a Civil Defence alert which may or may not be real. If real, they have about an hour before the missiles strike. In the end, whether or not the alert is real seems almost irrelevant – the fear of nuclear destruction is enough in itself to cripple these children.

An ordinary morning at school is interrupted by an alarm which rings in the principal’s office. It’s not the usual time for a test, but the staff are unable to reach the local Civil Defence authorities to confirm the alert. They have no choice but to treat it as real and decide to send the kids home to face possible disaster with their families. While the adults do their best not to pass on their panic to the kids, their very deflections provoke anxiety. The bulk of the film follows one teacher as she walks a group of kids home along peaceful country lanes. The young cast give convincing performances as they try to digest this unexpected break in normal routine and try to understand what it all might mean, panic gradually seeping in despite the sunshine and peacefulness of the day.

We learn from those left at the school that the alarm was due to a system failure, but that news doesn’t get to the kids right away and they have to deal with the reactions of their parents as they arrive home – from anger that the kids appear to be playing hooky to overwhelming fear of their own, with desperate praying for deliverance. Several kids seal themselves in a bomb shelter, one girl taking charge and immediately becoming a pushy martinet in the absence of her parents, who are still at work. In trying to behave like adults themselves, the older kids attempt to do what they’ve been taught in previous drills, but with little real grasp of what it all means.

With internalized fear impossible to alleviate, the final moments of the film descend into self-destructive despair. Although it doesn’t depict an actual attack, Ladybug Ladybug evokes the horror of living with the threat of nuclear war; in its way it’s almost as devastating as Peter Watkins’s The War Game (1965), though it depicts the psychological rather than physical consequences of living with nuclear weapons. This is a far more devastating film than Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach (1959), but inevitably received much less notice because of its small-scale and absence on big-name stars; it deserves to be better known.

The excellent cast of adults, including William Daniels, Nancy Marchand and Estelle Parsons, and the non-professional kids help to give Perry’s unfussy naturalism an almost documentary quality which adds to the deepening sense of horror. Leonard Hirschfield’s cinematography is served well by Kino Lorber’s 2K transfer, with a film-like texture, subtle contrast and a lot of fine detail. The only extras are a commentary by Richard Harland Smith and a brief trailer.

*

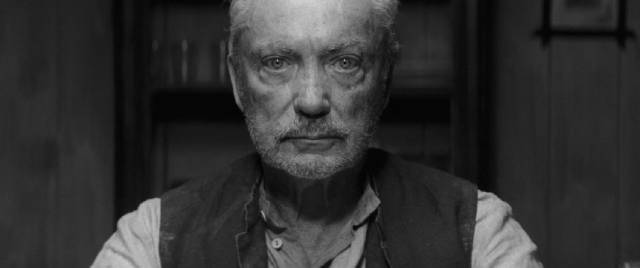

The Painted Bird (Václav Marhoul, 2019)

Technical perfection is not a guarantee of artistic success. Every frame of Václav Marhoul’s The Painted Bird (2019), photographed in exquisite black-and-white by Vladimir Smutny, is a riveting image in and of itself, regardless of the ugliness it depicts. I’m not sure whether I might have felt differently about the film if I hadn’t recently seen the restored version of Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985), a masterpiece with which it shares a great deal. Both are picaresque journeys through nightmare landscapes as seen by a young boy exposed to an inescapable series of horrors. The setting of both is Eastern Europe during the Second World War; in both many of the horrors aren’t directly rooted in the war, but rather are a reflection of the dark side of human nature which has been amplified by the war but exists apart from it. And both films are anchored by the remarkable performance of a boy without prior acting experience – Aleksey Kravchenko in Klimov’s film, Petr Kotlar in Marhoul’s.

And yet the impact of the two films is different, and I’m not entirely sure why. It may be that Klimov’s phantasmagoric nightmare remains rooted in the specificity of its time and place, enabling a deep emotional connection with Flyora, while Marhoul tries to transform its horrors into a kind of universal allegory of the monstrousness of human beings. This is signalled by an initial uncertainty about the period in which the film is set; the villages which dot the landscape and the people who inhabit them might well exist in Medieval times, harsh and primitive and steeped in superstition. As the film opens, a boy runs through woods, pursued by other boys who eventually catch him, beat him, and then set fire to his pet ferret. One can only hope that was faked somehow, because it looks all too real as the burning animal runs shrieking in circles before dying. This visceral horror establishes a base note on which everything that follows rests.

Some time passes before the disorienting image of a German fighter passing high overhead abruptly pins the narrative to a specific time, although the people and places Joska encounters continue to bridge centuries between a distant past and a seemingly hopeless present. Joska lives with an old woman on a small farm, but she soon dies and he accidentally sets fire to the house, a double event which forces him to begin his aimless journey. He’s purchased by a village witch who convinces everyone he’s possessed; he stays with a violent miller who’s convinced that his younger wife is having sex with his hired man – the miller erupts during dinner and gouges the younger man’s eyes out with a spoon (for added effect, the house cats make off with the eyeballs).

Joska encounters a helpful priest, who takes him to live with a respected citizen who turns out to be a pedophile who rapes the boy – though Joska gets his revenge by trapping the man in a pit with hungry rats. And so the boy is used and abused by the people who populate this timeless landscape, but strangely finds some degree of kindness from soldiers in both the German army – a middle-aged private ordered to kill him, who instead lets him go – and the Red Army – a sniper who helps him before slaughtering men, women and children in a nearby village. These small acts of kindness are too few and far between to offset the sheer awfulness of the human species. The film is a catalogue of horrors which numbs the viewer into a state of nihilistic detachment.

Marhoul’s determination to generalize these events and people includes his use of a kind of Slavic Esperanto, a language combining elements of many languages which de-specify the location, and his casting of familiar western actors in key roles. Suddenly encountering Harvey Keitel as the priest, Julian Sands as the pedophile, Barry Pepper as the Russian sniper, Stellan Skarsgard as the German soldier who lets Joska escape, and Udo Kier as the miller threatens to tear apart the allegorical fabric being carefully woven around the unfamiliar, largely amateur Eastern European cast.

At almost three hours, The Painted Bird is an endurance test. Come and See, itself an incredibly harsh film, immerses us in its protagonist’s experience, illuminating the horrors of war; but Marhoul’s film keeps us at a chilly distance, observers of the horrors being inflicted on Joska rather than empathetic participants. What I came away with was little more than a feeling that human beings are irredeemable monsters and the world a terrible place to live. The enormous effort expended by Marhoul and his cast and crew seems to have brought them to a dead end, their craft aestheticizing the horrors rather than enlarging our understanding of the terrible things we are capable of doing to one another.

The film was adapted from a problematic source, Jerzy Kosinski’s 1965 novel. Kosinski was a controversial figure, a best-selling author followed throughout his career by accusations of dishonesty and plagiarism. When the book was first published it was believed to be autobiographical, but was eventually acknowledged to be purely fictional … with large chunks lifted from other Polish books generally unknown in the West. Does any of this have any bearing on Marhoul’s adaptation? Perhaps only in that, without a basis in the author’s own lived experience, the relentless catalogue of horrific abuses inflicted on Joska takes on an element of sadistic exploitation.

Eureka’s Blu-ray presents a stunning image scanned from the 35mm negative. Also included is a 125-minute documentary about Marhoul’s eleven-year effort to make the film, itself a fascinating account of struggle and determination.

*

First Cow (Kelly Reichardt, 2020)

Specificity of time and place is a powerful element in Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow (2020), a beautifully observed tale of friendship and modest ambition set in 1820s Oregon. Reichardt is a subtle director of quiet moments and the landscapes in which ordinary lives unfold. Here the desert expanses of Meek’s Cutoff (2010) give way to northwestern forests, and the particular experiences of women (Wendy and Lucy, Meek’s Cutoff, Certain Women) to those of two men whose natures are antithetical to the arrogance and aggression of those who surround them in a small pioneer community.

The pair are immediately established as outsiders. Cookie (John Magaro) is foraging for mushrooms in the woods when he encounters a naked Chinese man who tells him that he’s hiding from men who want to kill him. Cookie hides King Lu (Orion Lee), while suffering the abuse of the men he’s travelling with who are not happy with his inability to provide them with substantial meals. Having helped King Lu escape his pursuers, Cookie runs away from his own party and eventually meets the other man again when he arrives at a bustling settlement. Both struggling to survive, they share a shack and get to know each other.

The first scene at the hut establishes the main difference between this and the typical homesteading western; King Lu has invited Cookie in for a drink. When he goes out to chop some wood, Cookie takes a broom and sweeps out the shack; he also picks some flowers to brighten it up. This note of domesticity lays the groundwork for the two men’s friendship and the unusual way they find to support themselves in the community – a way which makes them perhaps the gentlest outlaws in the entire western genre.

Cookie was a baker back east and he longs to be able to make some cakes again. When the Chief Factor of the trading post (Toby Jones) imports the first cow in the region, the pair begin to steal milk at night. The fried cakes Cookie makes become an immediate hit with the rough men of the settlement, necessitating increasing theft to meet the demand. When the Factor hears about the cakes, he samples them and commissions Cookie to make a special cake for an upcoming gathering.

First Cow is about the civilizing effects of cooking, but also about the roots of American capitalism in theft and expropriation. Cookie and King Lu build a successful and profitable business rooted in Cookie’s talent and the theft of resources. The irony is that what they steal belongs to the local big shot rather than the land and the native population that the community as a whole is exploiting. Although the pair bring great pleasure to the settlement, and to the Factor himself, they do it by violating an inviolable rule – such theft must be directed downwards, not up towards the self-appointed masters.

While First Cow is suffused with a sweetness in contrast to the grubby hardships of life on the frontier, the risks taken by Cookie and King Lu increase and their success becomes overshadowed by the mounting possibility of violent consequences. The Factor is puzzled by the inability of his cow to produce substantial quantities of milk, a mystery solved when his servants discover that someone is stealing the milk at night. Once discovered, it’s only a matter of time before Cookie and King Lu will be caught, yet the desire for making just a bit more profit keeps them in the community longer than is safe.

The influence of Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971) seems obvious, both films allegorizing Westward expansion and the rise of rapacious capitalism as the deep source of American identity. The big difference is that Reichardt focuses on male friendship in this isolated setting rather than the conventions of heterosexual movie romance, providing a glimpse of an alternative to the rigidly defined roles enforced by violence which are essential to the traditional western.

The Lionsgate/A24 Blu-ray has a wonderfully textured image. Shot digitally, it’s been given a convincing film-grain quality, framed at 1.37:1, adding the impression that this is a film from an earlier era. The production design and costumes are beautifully detailed; the sense of authenticity makes it seem that we’re watching something somehow recorded back in the 19th Century. There’s a visceral quality which adds emotional weight to the engaging characters, making First Cow one of Reichardt’s finest films.

The only extra is a featurette (26:59) in which Reichardt and co-writer (and author of the source novel) Jon Raymond talk about the process of adaptation, and members of the cast and crew discuss the production.

Comments