Recent Arrow box sets

Arrow has been going all-out lately, issuing a number of well-produced box sets for genre fans’ summer viewing. In the space of a month, they’ve released Years of Lead, a collection of five Italian thrillers from the mid-’70s; Vengeance Trails, four spaghetti westerns from the late ’60s; and The Daimajin Trilogy, three Japanese fantasies from 1966. I binged them all in a couple of weeks, and although they’re an uneven bunch, there’s not a dud in the lot. I had previously seen two of the thrillers, one of the westerns, and all of the Daimajin movies (I have the three-disk ADV DVD set from 2002), but all of them gain from the new transfers and the context provided by Arrow.

*

Years of Lead:

Five Classic Italian Crime Thrillers 1973-1977

Italian genres tended to erupt suddenly, flourish briefly, and taper off as other, newer genres emerged. The peplum adventures of the 1950s continued into the ’60s, but around the turn of the decade period Gothic horrors gained ascendance. They in turn were overtaken by spaghetti westerns, which flourished in the second half of the ’60s while the industry was priming itself for the explosion of gialli in the early ’70s. Within a few short years, those perverse thrillers were overshadowed by the poliziotteschi. While the giallo focused on individual psychological derangement, often with an unwilling private individual drawn into investigating a series of brutal murders, the poliziotteschi were rooted in larger issues of social conflict, often with cops going rogue to fight organized criminals and political terrorists on their own terms. If the giallo owed a lot to Psycho (1960), the poliziottescho owed perhaps more to Dirty Harry (1971).

As with any such sets, the genre connections among the movies in Years of Lead are fairly loose. Only two of the five films are outright police action stories, while the others are closer to psychological studies of anti-social criminals, with the police remaining somewhat tangential. The former are Massimo Dallamano’s Colt 38 Special Squad (1976) and Stelvio Massi’s Highway Racer (1977), the latter Vittorio Salerno’s No, the Case is Happily Resolved (1973) and Savage Three (1975) and Mario Imperoli’s Like Rabid Dogs (1976).

Colt 38 Special Squad (Massimo Dallamano, 1976)

Dallamano was a top cinematographer before turning to directing – he shot Sergio Leone’s first two Dollars movies (1964-65), but was replaced by Tonino Delli Colli for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), so he went off to direct his own western, Bandidos (1967). His filmography is as unpredictable as that of any Italian genre filmmaker of the period, with horror, eroticism, and gialli mingled together. While themes and narrative concerns are all over the place, what remains consistent, not surprisingly, is Dallamano’s grasp on visual storytelling.

Having tackled the giallo (What Have You Done to Solange? [1972]) and blended the giallo with the poliziottescho (What Have They Done to Your Daughters? [1974]), Dallamano closed his directing career with a fast-paced, violent poliziottescho in 1976. Colt 38 Special Squad has some echoes of the second Dirty Harry movie, Magnum Force (1973), but here the motorcycle-riding killer cops are sanctioned by their bosses as the last line of defence against criminal/political violence.

After a shootout in which Inspector Vanni (Marcel Bozzuffi) kills his brother, the psychotic criminal known as the Black Angel (Ivan Rassimov) murders Vanni’s wife in front of their young son. Vanni’s boss gives the inspector permission to create an elite squad who will use the bad guys’ own tactics against them. In a series of escalating incidents, the squad itself begins to slip out if Vanni’s control, while the Black Angel embarks on a campaign of planting bombs around Turin ostensibly to blackmail the authorities, but more to satisfy his own violent appetite for chaos and provoke a confrontation with Vanni. The bombs and their bloody aftermath echo events actually occurring in Italy at the time, with various right and left political factions setting off explosions and committing assassinations.

Colt 38 Special Squad is a fast, well-constructed thriller in which both sides are drawn into a pathology of violence while ordinary citizens are caught in the middle.

Highway Racer (Stelvio Massi, 1977)

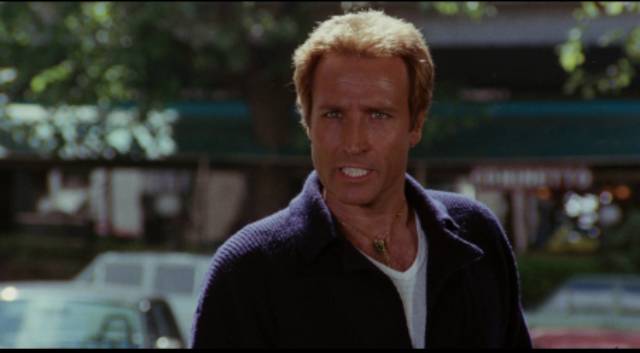

Stelvio Massi’s Highway Racer is a more superficial movie, existing mainly to provide the pretext for a series of high-speed chases and crashes. Like Dallamano, Massi began as a cinematographer and eventually switched to directing. During the second half of the ’70s, he more or less specialized in poliziotteschi, making movies with such genre stalwarts as Tomas Milian and Luc Merenda before settling down for a string of films starring Maurizio Merli, who for several years seemed to be De Niro to Stelvi’s Scorsese. Highway Racer was the first of these and somewhat perversely Massi had Merli shave off his big signature moustache for the role of hotshot Marco Palma – apparently in an attempt to make the thirty-seven year old Merli look younger to justify the character’s inexperience and naivete.

Palma likes to drive and is frustrated by the fact that the bad guys all have souped-up cars while the police are stuck with off-the-line Fiats. After a chase goes bad and Palma’s partner is killed, he swears that he’d have got the criminals if only he had a car like the one his boss Tagliaferri (Giancarlo Sbragia) had once driven. Tagliaferri knows the dangers of too much power under the hood, but he also recognizes Palma’s potential. When it becomes clear that a recent spate of bank robberies are the work of his old nemesis Dossena (Angelo Infanti), he dusts off his decommissioned Ferrari and hands Palma the keys. The younger cop goes undercover to get in with the gang and from then on there’s a whole lot of fast driving and highway mayhem courtesy of the unbeatable master of car stunts Remy Julienne, who along with his team performs some hair-raisingly dangerous feats – and how on earth did they get permission to crash a car down the Spanish Steps, a protected architectural monument in Rome?

Although there are various character conflicts and old scores to be settled, the reason Highway Racer exists is to offer the sheer spectacle of high-speed car action, and it delivers more than your money’s-worth of that, even if Merli’s lack of moustache is disconcerting.

in Vittorio Salerno’s No, the Case is Happily Resolved (1973)

No, the Case is Happily Resolved (Vittorio Salerno, 1973)

While this pair by Dallamano and Massi are focused on action, the other three movies in the set are more concerned with the personal psychology of violent criminals and the impact of their actions. It may be more a matter of personal taste, but the two films directed by Vittorio Salerno seem to me the best in the set. This is perhaps surprising because these are the only two films Salerno made as solo director; they were bracketed by two more which he co-directed with writer Ernesto Gastaldi. He also contributed to the scripts of a number of thrillers and spaghetti westerns, but despite living to 2016, his film career was confined to 1965-75. A pity, because in these two movies, he shows himself to be a superb filmmaker.

I’ve previously written here about No, the Case is Happily Resolved and will simply reiterate that it’s a remarkably assured thriller about an ordinary working class guy who witnesses a brutal murder and makes a series of bad decisions which end up seeing him become the suspect because the real killer, a respected professor, skilfully manipulates the legal system to trap him. The script is tightly structured, with everything hinging on the intersection between a rigidly stratified society and the psychological state of the working man shaped by that society. There’s a satirical element, but Salerno embeds it deep within a compelling story.

However, Arrow has made a puzzling decision with their edition which means that their disk will definitely not displace the excellent 2016 Camera Obscura edition from my collection. The film originally had a very bleak ending which suggested that truth and justice had no place in a society predicated on entrenched class interests. The producers didn’t like it and pressed Salerno to deliver something more upbeat. In a distant echo of F.W. Murnau’s Der Letzte Mann (1924, aka The Last Laugh), Salerno did as he was asked, but made the “happy ending” absurd enough to remain unconvincing, particularly in light of the relentless realism of everything which had preceded it. Camera Obscura retained the original ending and added this revision as an extra; Arrow reverses this, with the compromised ending tacked on to the feature and the original ending only available as an extra. This seems inexplicable to me – at the least they could have offered the film branched to allow the viewer to choose which version to see, but with only the one compromised option available, I won’t be watching their disk again because the producer’s ending damages the film too much.

in Vittorio Salerno’s Savage Three (1975)

Savage Three (Vittorio Salerno, 1975)

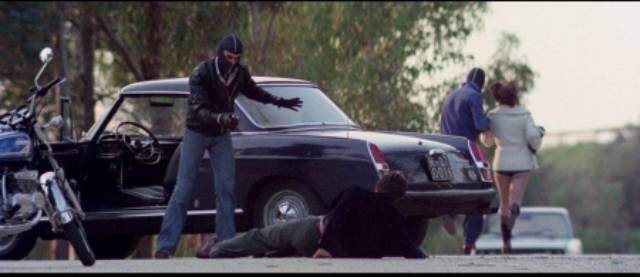

There are striking similarities between Salerno’s Savage Three and Mario Imperoli’s Like Rabid Dogs. Both feature trios of privileged young adults who relieve their boredom with increasingly extreme acts of antisocial violence. However, Salerno’s film continues with his analysis of class and the fracturing of Italian society in the ’70s, while Imperoli’s is more exploitative, aiming to shock rather than provoke deeper thought. Savage Three deals with three friends who have a secure middle-class existence with well-paying jobs; but that security offers them nothing beyond material comfort. The leader of the group, Ovidio Mainardi (Joe Dallesandro, giving one of his finest performances), works for a company which does data analysis with huge computers, the mechanized processing of information becoming a metaphor for the limited options available to him. Meanwhile at home, his wife Alba (Martine Brochard), a doctor, holds him in contempt while she openly has an affair with her boss in order to gain a promotion.

After watching caged mice in the company research lab turn on each other when their living space is reduced, he and his two friends, Giacomo (Gianfranco De Grassi) and Pepe (Guido De Carli), provoke a riot at a football match, just to watch the crowd turn on itself. The success of this little experiment sets them on a course of more personal acts of violence, committing increasingly sadistic murders. Among a group receiving computer training at the company is Commissario Santaga (Enrico Maria Salerno, the director’s brother, who also appeared as a newspaperman in No, the Case is Happily Resolved), who becomes increasingly interested in Ovidio, who is unable to prevent his slide into nihilistic despair at his own actions. The violence is occasionally shocking and graphic, but it’s always at the service of Salerno’s socio-political and psychological themes.

Like Rabid Dogs (Mario Imperoli, 1976)

Shock is the chief aim of Mario Imperoli in Like Rabid Dogs, with decadent, wealthy student Tony Ardenghi (Cesare Barro) leading his fellow students Rico (Luis La Torre) and Silvia (Annarita Grapputo) on a crime spree which begins with a robbery at a football stadium during which Tony kills a guard. This has little to do with a need for money, but much to do with the need for thrills to relieve their boredom. But unlike Savage Three’s roots in a nihilistic contempt for society, what energizes these students is a sadistic sexual energy – the addition of a woman to the mix generates tension between the two men which is increasingly released through acts of violence, acts which Silvia enthusiastically takes part in. Salerno approaches the violence in his film with a degree of detachment which is absent here, pushing Like Rabid Dogs closer to something like Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972).

On the trail of the trio is Commissioner Paolo Muzi (Jean-Pierre Sabagh), who for some reason quickly attaches his suspicions to Tony, partly it seems because he despises the social privilege enjoyed by Tony’s wealthy father, Enrico Ardenghi (Paolo Carlini). In his pursuit of the thrill-seekers, he exploits policewoman Germana (Paola Santori), whom he puts in harm’s way – after she’s almost raped by Tony, Muzi is aroused and all-but forces himself on her. This conflation of violence and sex infuses all the crimes committed by Tony and his friends, giving the film a queasy atmosphere.

Apart from a movie called Canne Mozze, which appears to be a kind of remake of Like Rabid Dogs made the following year, Imperoli’s only other credits are five erotic dramas made between 1973 and 1977.

All five movies in the set get excellent transfers and substantial extras in the form of lengthy interviews with key cast and crew members. There’s also a twenty-minute overview of the genre by critic Will Webb.

*

in Massimo Dallamano’s Bandidos (1967)

Vengeance Trails: Four Classic Westerns

It’s been a while since I dipped into the spaghetti western pool, other than watching a Mill Creek Blu-ray double-feature a couple of years back of Giorgio Ferroni’s Fort Yuma Gold (1966) and Paolo Bianchini’s Gatling Gun (1968), which were diverting enough but hardly stand-outs in a crowded field. That is definitely not the case with Arrow’s excellent four-disk set, Vengeance Trails, which showcases movies which for the most part diverge from the genre-defining style exemplified by Sergio Leone’s four key features. Although there are glimpses of arid landscapes in this set, forests and grassy plains and mountains predominate, with much action taking place in bustling towns. And to some degree, mythic qualities give way to a more human scale of individual psychology. Two of the films even edge into horror territory – not surprisingly, these were directed by Lucio Fulci and Antonio Margheriti.

Massacre Time (Lucio Fulci, 1966)

Fulci’s Massacre Time (1966) opens the set, representing a surprising yet prescient turn in his career. Best known at the time for comedies, particularly a series of movies starring the comic pair of Franco Franchi and Ciccio Ingrassia, the darkness and violence of this western point towards the gialli and horror films for which Fulci would become famous in the ’70s and ’80s.

Prospector Tom Corbett (Franco Nero, fresh from Sergio Corbucci’s iconic Django) gets a message calling him home to Laramie Town, where he finds the family estate in ruins, occupied by the henchmen of local big shot Scott (Giuseppe Addobatti), while his brother Jeff (George Hilton) has become a bitter alcoholic wasting away in a humble adobe shack with their childhood nursemaid Mercedes (Rina Franchetti). Jeff is hostile and Mercedes urges Tom to leave immediately. When he goes to visit Carradine (John Bartha), the man who sent the message summoning him, the entire family is slaughtered by gunmen who leave Tom himself untouched.

With Jeff’s help – despite being a drunk, he’s a deadly gunfighter – Tom heads for Scott’s ranch. There’s an elegant garden party going on and Tom’s intrusion is particularly unwelcome to Scott’s psychotic son Junior (Nino Castelnuovo), who amuses the guests by savagely beating Tom with a bullwhip until Scott steps in to stop it. Junior would obviously have liked to kill Tom – we’ve previously seen him shoot down an unarmed farmer, and in the film’s opening sequence he amused himself and his friends by using a pack of dogs to hunt down and kill another man. When Junior’s henchmen ride by and kill Mercedes, Jeff finally sets aside his animosity and joins Tom in his mission to destroy Junior and his father. As the climax approaches, Tom finally learns some disturbing truths about his own identity, the roots of Jeff’s hatred, and the real reason he was summoned home, and by whom.

Fulci handles the trappings of the genre well and stages the violent action with skill, greatly aided by an excellent cast. Franco Nero and George Hilton anchor the film as the conflicted brothers and Castelnuovo is chilling as their insane nemesis. It seems odd that Fulci would have returned immediately to more Franco and Ciccio comedies, making only two more westerns a decade later with The Four of the Apocalypse (1975) and Silver Saddle (1978), by which time he was firmly established as an accomplished director of gialli and about to launch into his horror phase.

in Maurizio Lucidi’s My Name is Pecos (1966)

My Name is Pecos (Maurizio Lucidi, 1966)

Maurizio Lucidi’s My Name is Pecos (1966) is the most conventional of the movies in the set, though it has the distinction of making a Mexican peasant-turned-gunfighter its hero. Pecos (Robert Woods) returns to the town of Houston seeking revenge on the outlaw Joe Clane (Pier Paolo Capponi), who murdered his entire family. Clane is in the midst of dealing with problems of his own, the loot from a robbery having disappeared with Steve (Peter Carsten), a treacherous member of his own gang. Pecos edges into this conflict, aided by his near-invisibility as a Mexican.

It’s refreshing to have the typical racial dynamics upended, adding to the satisfaction of seeing the laconic Pecos gradually destroying Clane’s gang. But perhaps the most interesting character is Morton (Umberto Raho), the venal town undertaker who stirs things up in order to amplify conflict and killing for his own profit.

Bandidos (Massimo Dallamano, 1967)

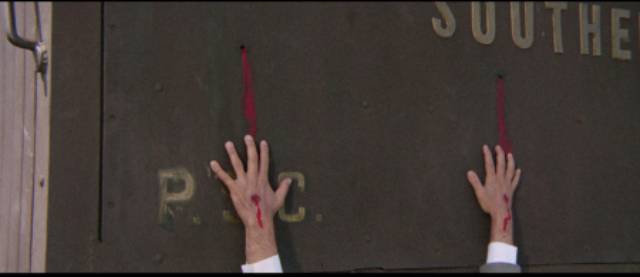

Massimo Dallamano’s Bandidos (1967) is far more ambitious, with the former cinematographer excelling at visual storytelling as well as giving psychological depth to an interesting collection of characters. All the key players are introduced in a spectacular opening sequence in which the gang of outlaw Billy Kane (Venantino Venantini) attacks a train and, during the robbery, kills almost everyone on board. One man survives because the train’s guard throws him off just before the attack for not having a ticket. The other survivor is sharpshooter Richard Martin (Enrico Maria Salerno), who has been looking for Kane to settle an old score. Martin, who trained Kane as a gunfighter for his sharpshooter show, feels responsible for what his protege has done since deciding that robbery is more profitable than show-biz.

When Kane finds Martin on the train, he doesn’t kill him; instead he shoots his former master in both hands, leaving him crippled and unable ever to hold a gun again. Having performed this act of symbolic castration on his metaphorical father, he concludes the violent scene by betraying the Mexican gang of Vigonza (Chris Huerta), which assisted on the raid. Dallamano cements a tone of tragedy by ending this opening sequence with a slow, sombre tracking shot along the length of the train, showing the scale of the massacre for which Martin bears some indirect responsibility.

Some years later, we find Martin plying his seedy sideshow trade in a small town, his new protege Ricky Shot barely beginning his performance when an irritated audience member pulls his gun and kills him. Outraged, Martin follows the man and his companions into the saloon and, despite his crippled hands, starts a fight. Unbidden, another man in the bar joins in. This man (Terry Jenkins) asks Martin to take him on as a replacement for the dead partner, taking the name Ricky Shot as much to maintain the existing signage as to conceal his own identity as the man we saw thrown off the train, who was later convicted for murder as a suspected participant in the robbery. Having escaped from prison, he’s on the track of Kane’s gang, hoping that he can find just one man who will clear his name by swearing that he wasn’t involved.

Dallamano’s elegant visual style and the excellent cast are well-served by a script which grounds its tragedy on a well-observed human scale. Bandidos is the story of a father with two sons, one of whom has brutally betrayed him, the other assuming the role of avenger of his father’s honour. The various layers of conflict – Kane’s henchman Kramer (Marco Guglielmi) turns against his boss, aligning with the previously betrayed Vigonza, who himself wants revenge – all serve the central narrative of Martin’s quest to atone by bringing down the son who turned to the darkside. The film is sombre, but not without humour, and Salerno gives one of his finest performances as a decent man tormented by the unforeseen consequences of his actions.

And God Said to Cain (Antonio Margheriti, 1970)

While Dallamano maintains a degree of realism, narratively and psychologically, Antonio Margheriti (under his usual pseudonym Anthony Dawson) plunges the western into all-out Gothic horror territory in And God Said to Cain (1970). If Massacre Time pointed towards Fulci’s future horrors, Margheriti’s western draws on his earlier signature horror movies – The Virgin of Nuremberg (1963), Castle of Blood (1964), The Long Hair of Death (1965) – to create a dense nightmare story of violent revenge full of supernatural intimations.

After ten brutal years in prison, former Confederate officer Gary Hamilton (Klaus Kinski) is pardoned and immediately heads back home to deal with the people who betrayed him – Acombar (Peter Carsten), who stole a shipment of gold at the end of the Civil War and framed Hamilton for the robbery, and Maria (Marcella Michelangeli), Hamilton’s lover who could have provided an alibi for him but instead threw in with Acombar. Catching a ride on a stagecoach, Hamilton encounters Acombar’s son Dick (Antonio Cantafora), an officer cadet heading home from West Point. Getting off at a remote desert waystation, Hamilton tells him to let his father know that Gary Hamilton is back and will see him at sundown.

When Dick passes on the message, he is puzzled by the fearful look which passes between his father and Maria, but no one is willing to enlighten him. Meanwhile at the waystation, Hamilton gets a horse and a rifle from an old acquaintance who warns him that a big storm is coming. That storm, with a threatening tornado, is an embodiment of Hamilton’s vengeful rage, providing cover for his mission and hindering the efforts of Acombar’s henchmen to stop him.

After this introductory section, culminating with Hamilton’s arrival in town at sunset like a spectre conjured by the windstorm, the rest of the film takes place in a single night with the wind blowing incessantly, the air full of dust and straw, the noise and darkness concealing Hamilton’s movements as he relentlessly decimates Acombar’s men. Beneath the town are mine tunnels and old caves which Hamilton knows intimately, enabling him to move about the town unseen, emerging to strike and immediately disappear again. He takes on the character of a ghost, a supernatural avenger grimmer and more determined than Clint Eastwood’s nameless drifter in High Plains Drifter (1973).

Margheriti orchestrates the action superbly, escalating the levels of violence as Acombar becomes increasingly unhinged. When Dick eventually learns what his father did, he sides with dad rather than the man his father wronged, his own eventual fate an ironic coda to this family loyalty. Maria too pays for her betrayal, and the final showdown between Hamilton and Acombar takes place in a room of mirrors, for a climactic nod to Orson Welles and The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

Not only is And God Said to Cain one of Margheriti’s finest movies, it also provided Kinski with his sole lead role as a hero – albeit an obsessed and murderous hero – and even dubbed with an American accent his performance is impressive, controlled, and nuanced. Usually cast as villains, as Hamilton he reveals a potential which for some reason was never again exploited.

If My Name is Pecos seems rather ordinary, the other three movies in Vengeance Trails reveal the range of styles and tones possible within the genre. It’s much richer than its original reputation allowed – back when these movies were new, although popular with audiences, many critics (particularly in the States) looked down on them. They were seen as a bastardization of a venerable American genre. But in hindsight, with the distance between history and narrative myth in that genre so clearly apparent, this alternate interpretation of Western mythology seems just as valid, and the work of these European filmmakers just as worthwhile as that of Ford, Hawks, Mann, Boetticher and other masters of the genre.

In line with other recent Arrow releases, this set is beautifully produced, with 2K transfers from the original camera negatives, a commentary for each movie, and numerous interview featurettes with key cast and crew members, as well as critic Fabio Melelli. There’s also a substantial 50-page booklet with critical essays on the genre and each of the films by genre authority Howard Hughes.

*

The Daimajin Trilogy

Meanwhile, heading around the world and further back in time, Arrow has given the deluxe treatment to Daiei’s mid-’60s experiment in genre blending. Made rapidly and released between April and December 1966, the three Daimajin movies attempted to introduce giant monster action into the familiar samurai genre. Although the series didn’t really take off and never received a lot of love from fans, production values are consistently good and the effects work is some of the best achieved by the studio which nonetheless had much more commercial success with their giant flying turtle Gamera.

The three films, Daimajin, Return of Daimajin and Wrath of Daimajin, adhere to a fairly rigid formula – established order is upturned by violent and greedy forces which proceed to oppress and exploit the population; when things have reached an intolerable point, someone prays to the mountain god Majin and a great stone statue comes to life to stomp the bad guys (inflicting a fair amount of collateral damage in the process) and order in restored. The basic narrative structure is borrowed from Daiei’s Zatoichi series – and in fact it would take very little effort to replace Majin with the blind swordsman himself – and on that level the stories are quite effective; but audiences primed for kaiju mayhem found themselves frustrated because the god only shows up for the final fifteen or twenty minutes, giving the fantasy action a tacked-on feeling.

As a saviour, Majin leaves something to be desired. Unmoved by an hour or so of brutal oppression, he only wakes up when an innocent offers to sacrifice their own life in order to save the common people (a noblewoman in each of the first two films, a young boy in the third). And then he stomps around, rather careless of who gets hurt as he deals with the bad guys. But despite the conceptual weaknesses, Daiei’s effects department conjures up some spectacular imagery, blending live-action, miniatures and composites inserting the giant into full-scale sets almost seamlessly (there are occasional matte lines, but nothing egregious). All three films are a visual treat, with the third movie’s mountain snowscapes particularly evocative.

The trilogy was efficiently directed by three veterans of the Zatoichi series – Kenji Misumi, Kimiyoshi Yasuda, and Kazuo Mori – who root the fantasy in a recognizable cinematic universe. It’s a pity that writer Tetsuro Yoshida essentially recycled the same script for each episode. Although not overcoming these weaknesses, Akira Ifukube’s scores add a sense of majestic, epic scale which reminded me at times more of James Bernard’s music for Hammer’s Gothic horrors than Ifukube’s own kaiju themes for Toho’s Godzilla movies.

All three films look fine, particularly when compared to the old DVD edition, with each film getting a commentary, an overall introduction to the series by Kim Newman and an overview of the effects by Ed Godziszewski, an interview with Professor Yoneo Ota about the production of the trilogy, a storyboard comparison for the second film, and a feature-length interview with cinematographer Fujio Morita about his career at Daiei and his work on the trilogy. The three disks come in slim cases inside a beautifully designed box which matches the packaging on Arrow’s complete Gamera set. Plus there’s a 100-page book of essays and artwork. While the trilogy remains a minor diversion, Arrow’s release is a major addition to any fan’s collection.

*

TECHNICAL NOTE: I discovered something odd, and interesting, from the Savage Three and Bandidos disks. The labelling indicates that the sets are coded for Region B, so I had my player set accordingly, and before these two movies there are text notes indicating that certain shots had been censored on the advice of the British Board of Film Classification – specifically, the shots of the mice tearing each other apart in Savage Three and a couple of horse falls during the attack on the train in Bandidos. Rather than re-editing these sequences, Arrow simply blacked out the shots, which is extremely distracting. When I mentioned this in passing to a friend who also had the Years of Lead set, he was puzzled because he hadn’t noticed anything. So I switched my player back to Region A and discovered that the disks would still play – and that those shots were actually there, but had somehow been filtered out by the region coding, an aspect of Blu-ray technology I hadn’t previously been aware of. The shots of the mice are definitely unpleasant, but the horse falls appear no worse than anything in any standard Hollywood western (in fact, one of the horses can be seen starting to stand up immediately after the fall). It’s not that I actually want to see animal violence, but Arrow’s method of dealing with this for the English market is irritatingly crude; that they found a technical way of concealing the offending shots while making them visible for other markets is intriguing.

Comments