Stanley Kwan’s Rouge (1987):

Criterion Blu-ray review

Ghosts have haunted Chinese cinema for a long time, and the 1980s were a particularly fertile period. However, while the main trends in popular movies at the time focused on horror or comedy, or a blend of both, often in the context of period martial arts action, Stanley Kwan’s Rouge (1987) uses a ghost story as the starting point for a meditation on the changing history of Hong Kong as the colony faced the uncertainty of its coming return to China after a century-and-a-half of British control.

Based on a novel by Lee Pik-Wah (Lillian Lee), whose work was adapted by other filmmakers into films as varied as Clara Law’s The Reincarnation of Golden Lotus (1989) and Temptation of a Monk (1993) and Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (also 1993), Rouge is a tragic romance which plays out in two very different Hong Kongs – the 1930s, when traditions rooted in radical class divides produced both glamour and injustice, and the 1980s, when social roles had radically changed and the city was facing an unknown fate with the coming shift from western to Chinese rule.

In the past, which opens the film, Fleur (Anita Mui) is a courtesan in a high-class brothel, much in demand. Chan Cheng-Pang (Leslie Cheung) is the only son of a wealthy, middle-class family; he becomes infatuated with Fleur after watching her perform a romantic song while dressed as a man, and begins a determined courtship. With his desire so obviously on display, Fleur plays with him, stringing him along, teasing and withholding, as his gestures become grander and more public. Well and truly hooked, Chan wants to marry Fleur, but this is socially impossible. When Fleur is presented to his mother (Sin Hung Tam), the older woman’s disdain is expressed in the form of polite condescension which Fleur can only suffer in humiliating silence.

As Chan spends more time slipping into an opium-induced haze at the brothel, Fleur comes to accept the impossibility of their romance ever coming to anything and the only solution seems to be a suicide pact – they can be together in death…

With a disorientingly abrupt cut we’re suddenly thrust into modern-day Hong Kong, the colourful fantasy of the past transformed into an urban space of towering buildings and roads full of traffic. At a newspaper office, Yuen-Ting (Alex Man) gives his long-time girlfriend, reporter Ah Chor (Emily Chu), the practical gift of new shoes to replace the ones she’s worn out in pursuit of stories. She has no time to stop and chat as she has a lead on some scandal behind-the-scenes at a beauty pageant. Just after she leaves, a woman dressed in a colourful cheongsam appears in the office and tells Yuen-Ting that she wants to place a personal ad in the hope of finding a missing person.

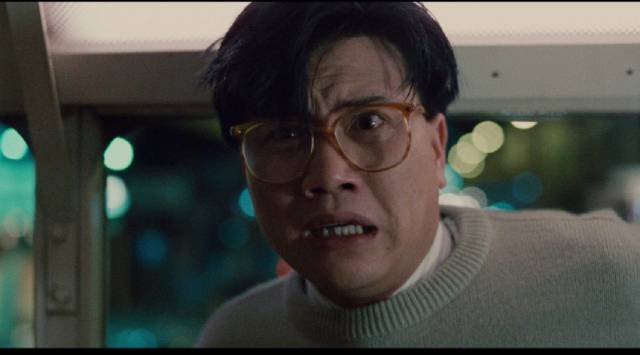

There is something strangely aetherial about the woman, whom we recognize as Fleur, dressed as she was fifty years ago and unaged. Yuen-Ting is unsettled by her as she seems to appear and disappear unnaturally – until, on the upper deck of a bus, she begins to tell him her story: that she died a suicide fifty years earlier and has now returned from hell hoping to find her lover who had failed to join her in the afterlife. The ad she placed is a private code telling Chan to meet her on the anniversary of the suicide.

Initially fearful, Yuen-Ting is drawn into Fleur’s tragic romance – as is Ah Chor once she’s convinced that Fleur is actually a ghost and not a rival – and Fleur moves in with the couple, who begin to investigate the story and aid in finding out what actually happened fifty years ago. Just as the city itself had transformed from what it was back in the ’30s, the nature of romance has changed. In the past, the socially-impossible relationship between Fleur and Chan was all heightened melodrama and flamboyant passions, while in the present, Yuen-Ting and Ah Chor’s relationship is pragmatic and rooted in gender equality. As they learn more about Fleur and Chan, they both agree that neither would give up their life for the other.

But the more they learn, the more illusory the tragic romance becomes. Fleur had not had complete faith that Chan would follow her into death and had surreptitiously poisoned him before they both consumed raw opium, essentially intending to murder him – and yet, while she had died, he had been saved and lived on. The colourful past turns out to have been a sordid lie, the romance more performance than reality, while in the present, stripped of the old class trappings, Yuen-Ting and Ah Chor’s relationship is more grounded.

As one of the first openly gay Chinese filmmakers, Stanley Kwan explores the nature of this performative kind of romance in interesting ways. There is a fluidity to the gender identities of Fleur and Chan – when they first meet, she’s performing as a man, while he has a distinctively androgynous delicacy which is underlined by his submissiveness during the courtship. She wields the power, teasing him as a way of amplifying his infatuation; his gifts become more extravagant as he submits to her authority over him – but that submissiveness extends to his ultimate inability to go against his parents’ authority over him.

Chan is uninterested in the family business and, under Fleur’s influence, joins a theatre troupe in which his androgyny becomes more overtly performative in elaborate makeup and costumes. But he ultimately doesn’t have the strength to maintain his resistance to the role assigned him as the son of a bourgeois family. The final irony is that, having survived the suicide pact, his life apparently didn’t amount to much and perhaps he would have been happier to die romantically and enter the afterlife with Fleur.

Kwan moves back and forth between periods, the contrast between the colourful period style of the ’30s and the more naturalistic approach to the ’70s, continually questioning the ways in which social structure shapes, traps or enables the expression of an individual’s character and constrains or liberates desire. The ghost story provides a vehicle, but in his hands it doesn’t conform to familiar genre tropes. Fleur is a particularly material presence, a solid physical reminder of the past rather than a spiritual echo; even though both Yuen-Ting and Ah Chor initially respond to her in a way dictated by genre, fearing her, they quickly become accustomed to her and treat her as a person, their opinions of that person evolving as they learn more about her life and past actions.

The contrast between periods is also embodied in the performances. There’s a sometimes extravagant theatricality to Mui and Cheung, while Man and Chu are almost comically ordinary. But if the past seems to be imbued with nostalgia, what is eventually revealed about the relationship between Fleur and Chan, particularly the manner of its end, strips away the illusion, giving the more prosaic present a greater sense of authenticity. Kwan’s control of tone unifies the radical differences between the two parallel narratives, displaying impressive assurance in what was only his third feature.

*

The disk

The 4K restoration from the original negative looks gorgeous on Criterion’s Blu-ray, with strong contrast and rich colours which really bring out the details of the production design. Audio is equally strong (the disk includes the original mono track plus an 5.1 remix), further contrasting the two periods through music and ambiences.

The supplements

The disk includes three substantial extras, beginning with a conversation between Stanley Kwan and filmmaker Sasha Chuk (39:34) which covers Kwan’s entire career and issues of gender in his work, as well as his own sexual identity. Those themes are further explored in Kwan’s documentary Yang ± Yin: Gender in Chinese Cinema (1:19:27), commissioned by the BFI in 1996 as part of the Century of Cinema project; this explores the themes of Rouge in a broader context through interviews with various directors whose work contains both overt and coded references to gayness – Chang Cheh, Chen Kaige, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Allen Fong, Ang Lee, John Woo, Tsui Hark, Tsai Ming-Liang and Edward Yang.

Still Love You After All These (44:07) is a memoir/essay film made by Kwan in 1997 on the cusp of the transfer to Chinese control which provides a personal impression of the city and Kwan’s reasons for staying and continuing to work there.

There’s also a trailer (4:40) and a booklet essay by critic Dennis Lim.

Comments