Nigel Kneale & British genre television

British TV has always been primarily a writer’s medium; since the ’50s, the biggest stars have tended to be the writers, with writers’ names attached possessively to projects. Television production was often built around writers such as Alan Bennett, Alan Bleasdale and Dennis Potter, who was one of the biggest, with each of his new productions greeted as serious works of dramatic art. At a lower level, there was Terry Nation, who became a household name with the creation of the Daleks for Dr. Who, and went on to make a more significant contribution to television fantasy with the mid-’70s post-apocalyptic series Survivors …

But the first great British television writer is not as well-known as he should be. When he joined the BBC as a staff writer in the early ’50s, Nigel Kneale fortuitously teamed up with the producer Rudolph Cartier and together they set out to transform the nascent form of TV drama, which at the time was unadventurous and stage-bound. They opened up the form by incorporating filmed elements into the live studio format to expand the available canvas, and they used the genre of science fiction, incorporating elements of horror, to get away from the cramped stories which prevailed at the time.

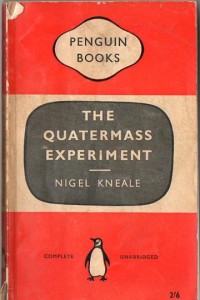

This was even more radical than it might at first appear, because those genres were barely visible on the pop culture landscape at the time. In fact, it could even be said that Kneale in collaboration with Cartier actually launched British horror with their initial production involving the brusque, determined scientist Bernard Quatermass of the British Rocket Group. The Quatermass Experiment was an enormous popular success, attracting millions of viewers on six successive Saturday evenings in the summer of 1953, and the movie remake rights were quickly purchased by a company called Hammer Films whose output until then had consisted mostly of low budget mysteries and comedies.

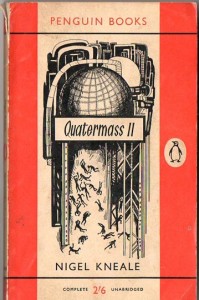

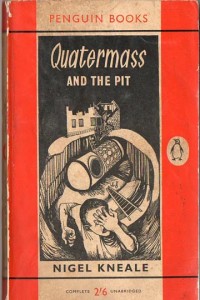

The feature version, slightly retitled The Quatermass Xperiment to take advantage of the censor’s X-certificate rating, was released in 1955, the same year that Kneale and Cartier presented the larger-scaled, more complex Quatermass 2 on the BBC. That too was remade by Hammer two years later, shortly before the third and most ambitious serial, Quatermass and the Pit, was broadcast. Kneale was unhappy with these Hammer films, largely because of the casting of blustery American ham Brian Donlevy as Quatermass, but also for the necessary simplifications required by compressing three-plus hours of drama down to 90 minutes. But in other ways, he was served well by having the films directed by Val Guest (who also made the Hammer version of Kneale’s TV play, The Creature, renamed The Abominable Snowman [1957]); Guest had a strong visual style and an almost documentary sensibility in his approach to the material which made both films powerfully plausible nightmares, their fantastic elements anchored by a sense of realism.

It was partly Kneale’s dissatisfaction, combined with the much bigger scale of Quatermass and the Pit, that delayed the Hammer adaptation of the third series for eight years. Kneale was much happier with Roy Ward Baker’s version of the material (1967, aka Five Million Years to Earth) and Andrew Keir’s more cerebral Quatermass.

My first encounter with Kneale’s work was a Christmas TV screening of Hammer’s Quatermass II in the early ’60s. Although I wouldn’t see the film again until I picked up the Roan laserdisk in the late ’90s, certain moments stuck with me vividly: the small meteorite cracking open and the alien parasite burning its way into a man’s face; the burned civil servant staggering down the steps outside one of the big “food” storage tanks; a glimpse of the seething alien protoplasm writhing inside one of the pressure domes …

But what really got me hooked on Kneale’s work was three orange-covered Penguin paperbacks on a bookshelf at home, reprints of the original scripts of the three serials. I read them all when I was about eleven (savouring the photo inserts, and frustrated that I hadn’t been around to see them broadcast) and they ignited a taste for the genre which lasted for many years.

The impact of Kneale’s creation, the “rocket scientist” Quatermass who defeats three successive forms of alien invasion, can’t be over-estimated. These three serials opened up the technical and thematic possibilities of the broadcast medium and introduced an enduring strain of the fantastic into British television – somewhat debased by the cheap but successful children’s show Dr. Who, which debuted in 1963 (Kneale turned down an offer to write for the show), but also resulting in a series of excellent adaptations of M.R. James stories (including Jonathan Miller’s renowned Whistle and I’ll Come to You [1968]), a surprising number of sophisticated series aimed primarily at children (Sapphire and Steel [1979-82], Timeslip [1970], The Tomorrow People [1973] among others) as well as A For Andromeda (1961: Julie Christie’s debut), Survivors (1975-77), Moonbase 3 (1973) and, later on, such efforts as Stephen Volk and Lesley Manning’s Kneale-like Ghostwatch (1992), in which a live reality TV show broadcasting from the site of a supposed poltergeist haunting ultimately unleashes a powerful supernatural force which devastates the country.

But while Kneale is best-known (by those who do know him) for Quatermass, his work was far more wide-ranging than those impressive serials. Between the first two Quatermass outings, Kneale and Cartier produced a hugely controversial and influential adaptation of Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four (1954; Cartier apparently even received death threats from angry viewers). Along with his own original work, he adapted a number of other properties (including Wuthering Heights [1953]) for television and then in the late ’50s and ’60s branched out to write film scripts, including two adaptations of John Osborne plays for director Tony Richardson: Look Back In Anger (1959) and The Entertainer (1960), for both of which he was nominated for British Film Awards.

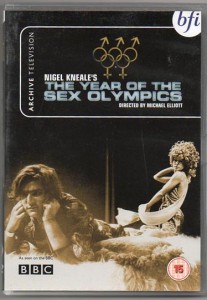

His two most significant works after this point were both again written for the BBC. The Year of the Sex Olympics (Michael Elliott, 1968) is a prescient social satire depicting a future in which the masses are kept placid with a constant diet of bad television, culminating in the invention of a “reality show” in which a family is stranded on a remote island, forced to fend for themselves while being observed round the clock by cameras. The producer, in order to shake things up, sends a psychopath to the island and the resulting violence proves to be a big ratings hit. The Stone Tape (Peter Sasdy, 1972) is, like Quatermass and the Pit, a brilliant combination of science fiction and the supernatural; a team of scientists working in a large country house discover that a “haunting” is actually a kind of molecular recording of past events trapped in the actual stones of the building, a recording which their equipment is capable of “playing back” – but it turns out that their scientific certainties are too limited and there are more dangerous levels to the phenomenon which they inadvertently unleash.

His six-part series Beasts (1976) is an interesting collection of character-based horror stories, but the previous year’s one-off drama Murrain (which led to the series) is better; again Kneale blurs the lines between psychology and supernatural in this story of a village which may or may not be plagued by witchcraft. Like the best of his work, Murrain gains in power from Kneale’s ability to apply a “rational” point of view to seemingly irrational events. His brand of horror was rooted in plausible social and psychological detail, an approach which gave him room to explore a wide range of themes – the growth of the military-industrial complex in Quatermass 2, with the inevitable rise of an accompanying police state; the genetic roots of human xenophobia, violence and religion in Quatermass and the Pit; the distortion and ultimately the destruction of human community by media which are determined to control and enforce consumer behaviour in The Year of the Sex Olympics.

Kneale, as one of the most imaginative scriptwriters of the mid-20th Century, deserves to be far better known than he is. While some key elements of his work have been lost because of the BBC’s practice of erasing tapes (as with 1963’s The Road) or not even recording some of the earlier live productions (only the first two episodes of The Quatermass Experiment still exist), much of his work has been made available on DVD. There’s an excellent region 2 set of the three Quatermass serials, and the three Hammer adaptations are all available, along with Beasts and the somewhat disappointing final Quatermass (1979), as well as the strange sit-com Kinvig (1981) and the gimmicky 2005 attempt to revive the original Quatermass Experiment as a live broadcast event. In addition, the BFI has released both The Stone Tape and The Year of the Sex Olympics. But, although the second performance of Nineteen-Eighty-Four was recorded and has on rare occasions been re-broadcast over the years, for some reason it seems never to have been released officially to home video (there are, however, a number of apparently bootleg editions available from various on-line sites). (NOTE: I did eventually obtain a copy of one of those grey-market DVDs later in 2011, and the BFI finally released it on Blu-ray in 2022.)

The Stone Tape and Anchor Bay’s editions of Quatermass 2, Quatermass and the Pit, and The Abominable Snowman all feature commentaries by Kneale, and the BBC’s three-disk set of the original serials has some excellent documentary and interview extras featuring Kneale, Cartier and various admiring commentators.

Comments

One thought on “Nigel Kneale & British genre television”