Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963): Criterion Blu-ray review

Apart from its inherent aesthetic appeal, black-and-white photography has the power to evoke moral complexities and ambiguities in a way that colour, which is so much closer to our everyday perception, can’t. Those infinite shades of gray focus our attention and make us more alert to the patterns formed by space and movement, by architecture and the figures which inhabit the visual world of a movie. This is what gives classical film noir so much of its impact; where the prosaic use of colour can normalize the most extreme events and behaviour, stripping away that colour lays bare the structures, moral and psychological, which lie behind the surface.

It’s all but impossible to imagine Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963) in colour. Black-and-white seems the natural medium for Harold Pinter’s complicated, and darkly comic, view of human social interactions. Pinter was already a prominent playwright with a distinctive style when he adapted Robin Maugham’s post-war novella, with over a dozen television adaptations of his theatrical works produced in the previous three years, and just one feature script behind him – Clive Donner’s big-screen version of his play The Caretaker, which was completed just before The Servant. His adaptation of Maugham launched a parallel career as a screenwriter in which, ironically, he specialized in adapting other writers’ work.

It’s also difficult to imagine a director other than Losey who could have brought out the particular qualities of Pinter’s script with such precision – and yet the script was originally developed for Michael Anderson, a journeyman whose work offers no indication of an affinity for this kind of material. (He would subsequently work with Pinter again on The Quiller Memorandum [1966], one of several mid-’60s spy movies countering James Bond’s fantasies of Empire.) Apparently there was initially some friction between Losey and Pinter over details, but the results of the collaboration show nothing of this, and the writer and director worked together again on Accident (1967) and The Go-Between (1971).

Maugham’s novella was written shortly after the War, depicting the incipient collapse of the traditional class system in the aftermath. Having been born into the aristocracy (he was an hereditary Viscount), he rejected a commission and enlisted in a tank regiment when war broke out, eventually being invalided out after suffering a severe head wound. He became involved in Middle East politics on behalf of Churchill, but abandoned that and turned to writing in the mid-’40s, a career which eventually ran parallel to his position in the House of Lords. All of which suggests that Maugham’s view of the story’s events was probably quite different from what emerged in the film. Whatever else The Servant may be, it’s certainly not a lament for the lost order.

Losey and Pinter’s approach is made clear in the opening scenes, a combination of sharply observed reality and metaphor. Under the opening titles, Douglas Slocombe’s camera pans around a bleak, wintry square in Chelsea, coming to rest briefly on the facade of Thomas Crapper & Co., plumbers to the royal family (the passing association of “crap” and royalty a tossed-off joke signalling the film’s attitude to class); we then glimpse a figure, bundled in an overcoat and hat and carrying an umbrella, crossing the street to a row house. He rings the bell, gets no answer, and after a moment tries the door which opens. Inside, he finds a house stripped bare and seemingly in decay – stained walls, peeling wallpaper – and finally discovers a man stretched out asleep in a chair. A polite cough gets no response, so he coughs again more loudly and the other man finally stirs to life.

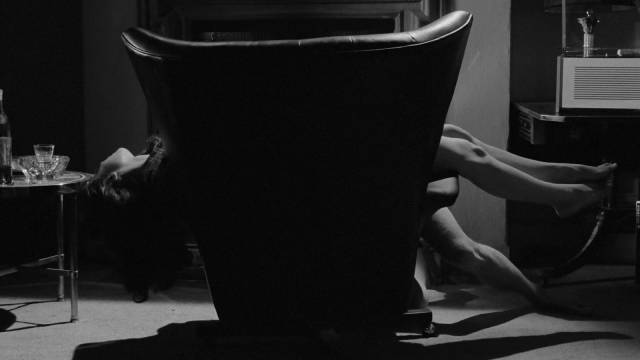

The visitor is Barrett (Dirk Bogarde), the sleeping man Tony (James Fox). Barrett has come about a position as manservant; Tony is the new owner of the house, recently returned to England. But although we quickly identify them as upper class property-owner and working class employee, the blocking and camerawork suggest a more complicated relationship. The house and its occupant seem derelict, in a state of stasis, almost as if Tony were in suspended animation and Barrett had roused him to consciousness – a lower class prince waking a dissolute sleeping beauty. Barrett is deferential, but there’s something in his tone, in his eyes, which indicates that he’s playing a part with which he doesn’t actually identify.

Tony says he needs a man who will do “everything”, taking for granted the roles which Barrett seems to be mocking. Tony, born to privilege, can only function if someone else takes care of all the details of life; Barrett says he’s up to the job, and quickly begins to bring the house to order, making all the decisions about decoration and furniture, imposing his own sense of taste and style against Tony’s occasional half-hearted suggestions. And yet, rather than pushing back against his hired man, Tony becomes completely dependent on him. The upper classes, in order to enjoy their privilege, are utterly dependent on those supposedly inferior to themselves, their dominance resting entirely on a shared belief in the natural order – a belief which, it is clear, Barrett doesn’t share in the least.

The strangely symbiotic relationship between the two men is complicated by the presence of two women. Vera (Sarah Miles) arrives from up North, presented as Barrett’s sister and brought in as a maid. However, Vera is actually Barrett’s lover and, although it’s unclear what the servant’s ultimate motives might be, she seduces Tony. Meanwhile, Tony’s fiancee Susan (Wendy Craig) senses that all is not well in the household; although she belongs to the upper class herself, as a woman she has experience navigating a social world defined and controlled by men and she quickly senses subterfuge in Barrett, taking an immediate dislike to him.

But even as the situation deteriorates and Tony discovers that he is being mocked behind his back by Barrett and Vera, his investment in the master-servant relationship and belief in the immutability of their roles make it impossible for him to break free; Barrett plays up the duplicity of women, asserting that both he and Tony have been played by Vera, their shared victimhood binding them more closely together. And yet, he seems to have no larger plan than simply upending the class system for his own amusement; having established a perverse kind of equality through rejecting the women, Tony and Barrett revert to an adolescent state evoking the homoerotic play of public school boys, which had long been a pillar of Empire. By the end, the two men are locked into this parody of the old order, Barrett the bully who has gained complete dominance over the weak-willed Tony. The futile perversity of that order is laid bare because the world in which it once flourished had ended with the War; whatever might replace it, neither Tony nor Barrett have managed to escape its trap. Barrett is no revolutionary, but rather an opportunist seeking to profit from something which has reached a dead end.

While its critique of class is thus limited, The Servant is both a wickedly entertaining black comedy and a sharply observant psychological drama, made with wit and precision, and played by a flawless cast. Dirk Bogarde conveys superbly Barrett’s toxic resentment of the system which defines him as less than the weak and feckless man he “serves”, while James Fox, with very little previous experience, is equally as good as that weak foil. Wendy Craig as Susan is the most aware of the characters, the only one who can see clearly what is happening inside Tony’s house, and Sarah Miles gives Vera an earthy, erotic power which disrupts the entire shaky order the other characters subscribe to in their various ways.

Largely confined to the interior of the house, the visual style approaches the exaggerations of Expressionism, with extreme high and low angles defining character relationships through a careful use of spatial connections – Losey emphasizes stairs and railings to suggest the layers of class and the ways in which class imprisons those unable to escape its constraints; he also makes extensive use of mirrors to evoke the unstable power dynamics of the shifting relationships. The connection between architecture and psychology is as powerful here as in the films of Hitchcock and Lang.

Although The Servant finally established the exiled Losey as a major figure after a decade of trying to find his voice in a place so different from the world he had known back in the States, and while it pointed the way towards Pinter’s future career as a screenwriter, it almost didn’t see the light of day. Financed by Warner Brothers, it was initially viewed very negatively – its bleak view of society and dark resolution were seen as uncommercial and the film was shelved until someone in the London office needed to fill a hole in the schedule at the company’s flagship theatre in Leicester Square and went through their unreleased holdings. Impressed, he booked The Servant and, despite company misgivings, the film received critical praise, attracted an audience and went on to win and be nominated for numerous awards in England, Europe and the U.S.

*

The disk

Criterion’s 4K restoration looks excellent on Blu-ray, with a rich range of grays and a great deal of detail in the image (needless to say, it’s a vast improvement on my two-decade-old Anchor Bay DVD).

The supplements

There are two-and-a-half hours of new and archival extras which provide a lot of information about the production and the creative processes of those involved. An audio interview with Losey (28:56) conducted by French critic Michel Ciment in 1976 covers how the project came about – apparently Losey had suggested Maugham’s novella to Bogarde a decade earlier when they worked together on The Sleeping Tiger (1954), the first feature Losey made in England (under the pseudonym Victor Hanbury), and the story eventually found its way back to Losey via Pinter’s script, which had been written for director Michael Anderson; Losey also talks about his working relationships with the writer and cast.

Film critic Imogen Sara Smith is interviewed about the themes and style which run through Losey’s four-and-a-half decade career (29:45).

Pinter shows up in an interview recorded at the National Film Theatre in 1996 (22:57) in which he talks about his work with Losey and, more generally, the differences between adapting other people’s work for the screen and his own writing for the stage.

In a brief interview excerpted from a 1992 television program, Bogarde talks about The Servant and his work with Losey on a number of other films. Interviews with the rest of the cast were recorded for a 2013 Studio Canal release, with Wendy Craig (5:46), Sarah Miles (10:52) and James Fox (47:30) discussing their work with Losey.

There’s also a trailer (2:46) and the booklet essay is by Irish author Colm Toibin.

Comments

I greatly enjoy the films that came out in Britain during the 60’s. I’m a fan of The Angry Young Man movement. Films such as Look Back in Anger and This Sporting Life looked at anguish of the working class quite distinctively.

Thanks for this great review of The Servant. I did see it once many decades ago but I need to track it down for another viewing.