DVD diary: another eclectic week – part one

If anything, my viewing seems to be becoming more random these days. I mean to apply some order to what I watch – to view the new Silent Naruse set from Criterion Eclipse, or the Columbia Sam Fuller Collection from two years ago which I recently got hold of – but there are so many other things waiting that I end up just grabbing something off the shelf. This week, those “choices” ranged from a Jess Franco title to a collection of British television documentaries by Molly Dineen, from Fellini’s The Clowns to a southern fried artifact from the ’70s called Poor Pretty Eddie … so here’s the latest selection from my collection:

Molly Dineen got off to an impressive start in the mid-’80s when, still a student at the National Film and Television School, she came across a great character and started filming without a clear aim in sight. Colonel Hilary Hook was an elderly retired colonial soldier living in Kenya when she met him, a man who had scarcely lived in England at all, having spent a long life serving the Empire. He was charming, funny, and prone to expressing completely unacceptable attitudes (by today’s standards) about the Africans he lived among. When Dineen met him, he was finally preparing to move back to England as his Kenyan landlord was taking back his property. Dineen went on to observe Hilary’s frustrated struggles as he tried to settle into a country he was completely unfamiliar with, barely able to fend for himself without his servants, defeated by an electric can opener, or shopping at a supermarket. Although Dineen treats her subject with obvious affection, Home From the Hill (1985/87) is a frequently uncomfortable revelation of what Britain used to be.

The Molly Dineen Collection Volume One includes another colonial piece, My African Farm (1988), about an irascible woman named Sylvia Richardson, who paternalistically lords it over the African families who work on her land as she prepares to sell it to them. Disk one concludes with a fascinating look behind the scenes of an ageing, malfunction-plagued London Underground station, Heart of the Angel (1989), focusing on the workers who keep it running during the day and others who spend their nights cleaning and maintaining the place.

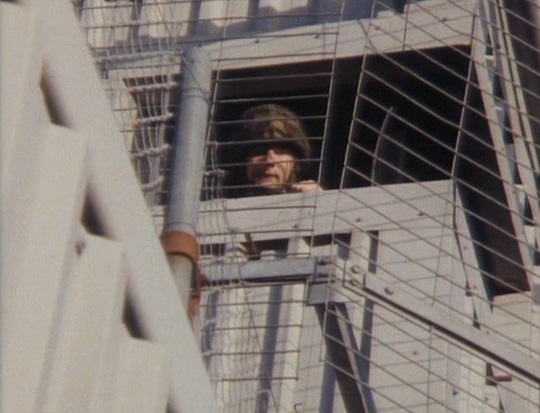

The second disk is even better, a three-part documentary about a unit of Welsh Guards posted in Northern Ireland before the ceasefire. In the Company of Men (1995) is a fascinating study of the institutional structure of the modern military, which benefits from remarkably frank access to the company’s officers and enlisted men. Shot mostly in and around a concrete-reinforced Royal Ulster Constabulary compound close to the border, with the constant uneasy threat of possible mortar attacks, the film evokes a strange mix of tension and boredom and the structural mechanisms which the army uses to maintain focus and discipline. Dineen treats her subjects with interest and empathy, but the sight of heavily armed men scuttling along the streets of a small picturesque village where the locals are going about their business has an almost science-fictional tone.

I’m already hooked on Molly Dineen’s work – like Marc Isaacs, she’s an attentive observer of interesting, yet typical individuals within the changing social environment of Britain – and I’m looking forward to the two further volumes promised by the BFI for later this year.

Fellini’s The Clowns (1970) has some of the appearance of a documentary, but is more of a personal meditation on a subject which had an incalculable influence on the director’s work. From his earliest films, Fellini’s work is inflected with a circus-like atmosphere and populated by comic grotesques, exaggerated figures which teeter precariously between the comic and the horrific, so when he claims at the start of The Clowns that he was terrified of clowns when he first encountered them as a child, it almost seems that the work which followed was an attempt to diagnose just what it was that had such an effect on him. In The Clowns, he combines interviews with ageing practitioners in Italy and France with lengthy performances shot at Cinecitta on a big top set. There’s a sense of melancholy running through the film as Fellini sees the clown as a figure already dying out, and The Clowns actually climaxes with a lengthy clown funeral sequence which echoes other parades in his work, like the dawn finale of 8½ in which all the protagonist’s paralysing indecision is swept away by a scene of spontaneous celebration.

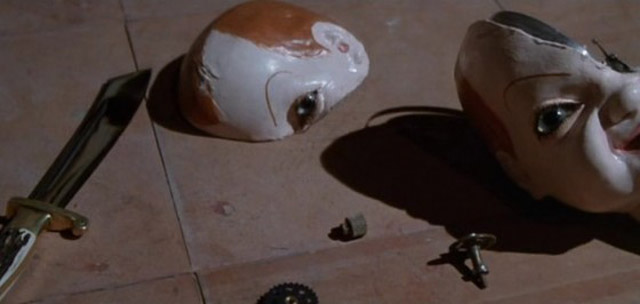

Continuing on the Italian front, I just watched the new Blue Underground Blu-Ray of Dario Argento’s breakthrough giallo, Deep Red (1975). Although his previous films (Bird With the Crystal Plumage [1970], Cat ‘o Nine Tails and Four Flies on Grey Velvet [both 1971]) had received some attention outside Italy, much of it was critical of their implausible narratives. For some reason, Deep Red produced a shift in the way his work was seen, an appreciation of his visual style and the elaborate violent set-pieces, which made the supposed narrative weaknesses seem unimportant. The new Blue Underground edition contains both the export Deep Red version and the original, longer Italian cut, Profondo Rosso. Watching them back to back, I have to say that the shorter, English version is the better of the two. The additional material in the Italian cut consists mainly of some extended conversations and several tedious “comic relief” scenes involving the protagonists (David Hemmings and Daria Nicolodi) in a tiny malfunctioning car, and the lead police investigator struggling with an uncooperative vending machine. Although the narrative itself is no less far-fetched than those of the earlier films, it still plays better when the focus remains on the murders and Hemmings’ attempts to solve them.

Made the same year as Deep Red, Poor Pretty Eddie is perhaps even less coherent, but at least as entertaining. Made by pornographers trying to go legit, Eddie has a surprisingly good cast for a low-budget regional production, with singer Leslie Uggams making a perhaps ill-advised attempt to break into acting as the lead character Liz, a singer who makes that fatal mistake of driving alone through the rural South on her way to her next gig. Although she doesn’t run afoul of cannibal hillbillies, things really don’t go well for her. When her car breaks down, she finds herself at a remote bar/motel owned by an ageing ex-burlesque performer named Bertha (Shelley Winters) who clings to her young lover, Eddie, who’s a country-music wannabe who sees Liz as his way to stardom. So Eddie basically kidnaps and rapes her; the local sheriff (the always great Slim Pickens) and justice of the peace (Dub Taylor) turn Liz’s accusation of rape against her and humiliate her in public; feeling helpless, she goes more or less comatose and gets dragged into a grotesque wedding with Eddie, which ends very badly when the handyman Keno (Ted Cassidy) puts an end to Eddie’s madness with a shotgun. Strangely, the cast really throw themselves into this craziness and the movie is shot through with some striking imagery and interesting editing effects.

Meanwhile, Masters of Cinema in the UK have just brought out a new edition of Fritz Lang’s penultimate work, the two-part Indian Epic (The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb [1959]). Lang’s return to Germany after so many years in Hollywood was also a return to his roots as the project was a remake of 1921’s The Indian Tomb, a silent epic written by Lang and Thea von Harbou which he was originally supposed to direct until producer Joe May decided to do it himself. Lang’s version was not well-received in 1959, with its fantasy vision of India and Saturday matinee serial plotting, full of romance, danger, escapes and elephant parades. But it’s ravishingly beautiful to look at and charming in its old-fashioned storytelling. While it would be impossible to better the Fantoma transfers from 2001, Masters of Cinema has equalled them on this two-disk set, and added a fine commentary by Lang expert David Kalat. Kalat makes a strong argument for Lang being, even at his best (and admittedly the Indian Epic isn’t his best), a brilliant pulp artist, working in popular genres, manipulating cliches and stereotypes – or rather, in many cases, creating those cliches and stereotypes. Within that context, the Indian Epic can be seen as the work of an experienced master relaxing and enjoying himself as he completes something which he started almost forty years earlier.

I debated with myself whether to mention this next title as it’s probably the hardest to justify watching, but honesty compels me to admit that I also watched Jess Franco’s Lorna the Exorcist (1974). Objectively, I guess I have to admire Franco’s sheer obsessive devotion to making images (IMDb lists almost 200 titles over 53 years), but apart from some of the earliest works (The Awful Dr. Orloff and The Sadistic Baron von Klaus [both 1962]) which stand as fine examples of Euro horror from the days when people like Mario Bava were at the height of their powers, I find most of Franco’s movies unwatchable. Critics like Tim Lucas and Stephen Thrower would be quick to point out that this is due to my own limitations, a clinging to the conventional idea of what makes a “well-made film”, but I can’t help it … many of the Franco movies I’ve seen simply bored me. But I can’t say that about Lorna (by the way, there’s not an exorcist in sight; the title is just a blatant attempt to cash in on the previous year’s American hit); this was apparently one of eight movies directed by Franco in 1974, but it’s more coherent than many of his films and at times visually interesting. Eighteen years after a mysterious woman somehow mysteriously gave a businessman success, she returns to claim her fee – his daughter, just turning eighteen. The man tries to back out of the deal, but of course it’s too late. So – a basic Faust storyline, but glossed by Franco with multiple layers of sexual obsession and perversion … there’s an odd dreamlike tone to the film which keeps it afloat through often clumsy scenes and lengthy stretches where not much happens.

Dream-like incoherence is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, it’s one of the chief attractions of a lot of Asian horror. One of my favourites in this genre is Takashi Shimizu’s original V-cinema version of Ju-On, a two part ghost story with multiple narrative elements which gradually click together to form a single story about a “grudge”, a supernatural animosity arising from the anger of someone who died badly and which contaminates anyone who comes into contact with it. The original Ju-On diptych is one of the creepiest, scariest movies I’ve seen; but it also gave rise to a kind of mini industry which offered diminishing returns. Shimizu himself directed two theatrical features in Japan based on the original, with bigger budgets and better production values, but while they had their moments, they couldn’t help but feel like he was simply repeating himself, recreating the same effects as before but with less impact. Then the series caught the eye of American producers and Shimizu went on to re-do the same story again as The Grudge 1 and 2, but with American stars; again, the movies had their moments, but could any director keep creating the same scenes again and again without getting stale? Anyway, being a completist, I couldn’t resist when I came across Ju-On: White Ghost/Ju-On: Black Ghost this week, a return to the series’ V-cinema origins, but with Shimizu no longer involved. I admit that I didn’t expect much, and the first of the two one-hour stories, White Ghost (directed by Ryuta Miyake), merely provided a simulation of Shimizu’s technique – the episodic structure, the scare moments – but it never coheres into a fully developed narrative and the scares are often fumbled. The second story, Black Ghost (directed by Mari Asato), however, comes close to the original with its depiction of the “stain” spreading out to infect a group of people whose paths cross, conjuring up a pervasive sense of the supernatural threat which seems to permeate every moment, every space, so that even when a specific scare is absent, you feel an uneasy sense that something nasty is about to appear.

To be continued …

Comments