Lost films and alternative histories

Although dates are an artificial and arbitrary invention we use to keep track of the passing of time, we tend to attach significance to them – which is partly why, with the transition to 2024, I find myself in a somewhat introspective and melancholy mood. Sliding towards my seventieth birthday, I suppose it’s quite normal to look back and wonder what the heck I’ve been doing here over seven decades, but that impulse has been amplified by the resurfacing in the past couple of years of an experience from forty years ago: quite unexpectedly I’ve found myself becoming a small part of the official history of David Lynch’s Dune (1984).

I suppose I nudged myself in that direction when I launched my website in 2010 and posted the journal I had kept during my summer on set in Mexico City, and again five years later when I self-published the journal as an ebook to go along with what I considered my more significant history of the making of Eraserhead. Then, after yet another five years, both books were given an official publication by BearManor Media – again, I considered the Eraserhead volume the important one, with the account of my time on Dune a bit of a throwaway add-on. But by then, Denis Villeneuve was working on his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel and there was a new wave of interest in Lynch’s troubled movie. My book managed to catch a small part of that wave and I was tracked down and interviewed by Daniel Griffiths for the retrospective documentary on the production he was making for Koch Media’s upcoming 4K restoration of the film, and a year or so later I was interviewed again, this time by writer Max Evry, who was working on an oral history of the production.

Then before Max’s book was released in September, I came across the Dune volume by Australian academic Christian McCrea in Auteur Press’s Constellations series and discovered that my modest book had been used as a significant source (both the journal itself and the interview transcripts from the abortive making-of documentary I had been involved with). Then I was surprised to find my interview woven through three of the four sections of Max’s A Masterpiece in Disarray: David Lynch’s Dune, one of many voices to be sure, but nonetheless contributing to a detailed account of what had happened, what had gone wrong and why, and also what made this crippled film so special.

In a moment of synchronicity, I’d just finished reading Max’s book when I received a copy of the Canyon Cinema Foundation’s latest publication, Cinemazine #8: Cine-Espacios, which had been co-edited by former Winnipegger Walter Forsberg, an archivist/preservationist now living and working in Mexico City. Focused on the Mexican film industry and containing new and archival materials on the history of Mexican cinema, it Included an interview with me conducted by Walter about my experiences working at Estudios Churubusco on Dune. (Odd to see myself translated into Spanish!)

I bring this all up because I’m struggling a bit with the idea that what may have been the most significant part of my life occurred forty years ago. This is a subjective perception of course, so part of me wants to set it in context. It dominates because of its scale, because those events are inextricably connected to one of the major cultural figures of the past fifty years and I can’t help but feel that Lynch’s aura has left its traces on my own life even though our connection – which was tangential at best to his own trajectory – only lasted about three years.

What counterweight can the rest of my life offer? Compared to that brief period, it looks pretty scattershot – a stream of events and activities mostly driven by contingency rather than intention. Jobs taken simply because an income was needed to survive, money earned so that I could pursue what in retrospect seem like random amusements. I managed to travel and enjoyed visiting interesting places, often benefiting from connections made along the way – I spent the summer of 1984 in Italy, facilitated by contacts I had made on Dune, but a few years earlier I had also spent eight months in Hong Kong through family connections. I’ve spent time in Germany, France, and briefly in the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, even China and the U.S., and have lived in various parts of Canada… But apart from enjoying the experience in the moment, has any of this amounted to anything? At least I eventually got a book out of working on Dune.

From a creative point of view, the film career I had for about twenty years, beginning six years or so after that summer in Mexico, has been rewarding in ways the abortive Dune documentary project couldn’t be – there are completed works which may be seen, though obviously with a much lower profile. From my own early short films, which were shown at a few international festivals and sold to television in Canada, Australia and France, through the documentary work I did at the National Film Board (editing, co-writing, occasionally shooting), I was able to exercise whatever filmmaking talent I had, even teaching workshops and mentoring young filmmakers, some of whom went on to make more of a mark than I managed to make.

When my NFB career faltered (the Winnipeg office was essentially shut down), I landed one brief job on a mainstream feature (the dire Milla Jovovich-starring Faces in the Crowd [2011]), but I did manage to take advantage of local resources to make a couple of documentaries which I’m quite proud of (Going: Remembering Winnipeg Movie Theatres and CarFree: Stories from the Non-Driving Life), but I lack marketing skills so neither have been widely seen (though there has been gratifyingly positive feedback from those who’ve come across them) – I eventually posted them on Vimeo where they can be watched for free. But since then any creative impulse has been channelled into writing about movies here on my website.

I occasionally think about digging out the manuscripts of some of the novels I wrote back in the ’70s and ’80s – most were undoubtedly rubbish, but at least in my memory maybe three weren’t bad. Would it be worthwhile to take another crack at them? But then they’re rooted in the past too. Can’t shake this feeling that with time running out I ought to be doing something more, trying to top that landmark experience from four decades ago.

I suppose it’s not unusual for someone to look back and see their life as a long string of almost random events driven by chance … but in retrospect it’s tempting to criticize oneself for failing to make different choices, for not having set out with more purpose in a particular direction. It seems ironic to me that already in my teens I had possessed an interest in film and that when I arrived in Winnipeg at the age of eighteen I had found a summer job at a small film company where, ostensibly, I was training to be an assistant editor … an opportunity which had no follow-through until I joined the Film Group sixteen years later and discovered while making my own first small films that my deepest affinity was with editing. What if, back in 1973, I had been more driven and had not simply moved on to some other meaningless job when that summer job had ended, but had instead pursued a career in film?

I have no idea what specific opportunities might have been available, but it was only a few years later that the Winnipeg Film Group had been formed (with the involvement of a number of people I had met at Western Films). Somehow I had missed all that, yet another path not taken which might have launched me on a career in film. Of course, there’s no point in kicking myself now for being a dumb-ass back then, but it’s tempting. Over the years, watching movies and eventually writing about them, I’d fantasize about the films I’d like to make myself, but those fantasies would always be way out of reach and it didn’t occur to me to tackle something within my available means until my wife at the time urged me to join the Film Group in 1989.

Looking back now, it seems likely I wasn’t cut out to be a maker of features, but my temperament and interests, brought into focus over the past couple of decades thanks to the availability of so much of cinema history on disk, makes me think that my ideal role didn’t really exist back when I was casting about for something to do with my life. I envy Walter, who got a degree in film preservation and restoration in New York, worked as an archivist at the Smithsonian, and has now ended up in Mexico where he pursues his interest in cinematic ephemera – commercials, experimental films, television. I think I might have been quite happy scouring archives and the storerooms of labs and defunct distributors, unearthing the remnants of forgotten corners of the art which has, for some reason, remained such an important part of my life since childhood.

*

Vinegar Syndrome’s Lost Picture Show

Which is a very roundabout way to arrive at Lost Picture Show, a six-disk set released by Vinegar Syndrome to mark their tenth anniversary. While major studios once devoted resources to restoration of important films – I first saw several of Hitchcock’s films in a theatre when Universal did restorations in the early ’80s; one of these, Vertigo (1958), became a notable case for the pitfalls of restoration with the subsequent re-release in 1996 of a new version which not only “reinterpreted” some elements of the colour (original materials had faded, leaving a great deal to the restorers’ interpretation), but also altered the sound design by replacing original effects for a 5.1 DTS remix. Similar issues arose with the restoration of Orson Welles’ Othello (1953), which involved “fixing” Welles’ original sound edit which, because of the nature of the production, lacked what many deem acceptable technical polish.

Restoration isn’t simply a technical process, then; with the increasing sophistication and versatility of digital tools, there’s always a temptation to interpret and “improve” on the material. This is not exactly the same as the issue of a filmmaker altering their work in the digital realm – from George Lucas essentially remaking his movies and erasing the originals to Ridley Scott tinkering with Blade Runner to William Friedkin altering the colour palette of The French Connection – because restoration technicians (artists?) are at a further remove from the films they work on, films which are often much older, where it’s not always clear what the original theatrical quality was like. This is why the internet is full of discussion threads about the validity of image and sound on disk, and outrage at changes made by those who can’t resist “fixing” flaws baked into a movie (unfinished effects in, say, Hammer’s The Devil Rides Out [1968] for instance).

But there’s an entire realm far removed from these continuing efforts to preserve the canon as the underlying materials age and inevitably deteriorate. That’s where companies like Vinegar Syndrome, Severin, American Genre Film Archive, Arrow, Indicator and occasionally the BFI come in. A majority of the movies made since the technology took hold in 1896 have vanished because for a very long time, as a commercial medium, value was seen only in terms of box office; all too often, when a movie’s theatrical life had been exhausted prints and even negatives were discarded (in the days of nitrate, these materials were melted down to salvage the silver which was an integral ingredient). This is why, even when something has survived, it’s often only in the form of a battered print which had been stored away when it was no longer profitable to exhibit it. In many cases, this kind of survival is essentially accidental – like the 16mm reduction negative of Fritz Lang’s almost complete Metropolis (1927) which was found stored in an Argentinian archive in 2008, or collections of films discovered in Dawson City, in New Zealand, or sealed in a barrel in a cellar in Blackburn for a hundred years. Sometimes these discoveries are significant for filling in gaps in a well-known history – the New Zealand cache included John Ford’s Upstream (1927) and Alfred Hitchcock’s earliest surviving feature The White Shadow (1924), both long believed lost – but film history has a much vaster quantity of more obscure and disreputable product, made quickly, often for little money, aimed at making a quick buck by promising audiences something they couldn’t see in mainstream theatres … in a word, exploitation.

The survival of these movies has always been more tenuous than that of studio productions – with the latter, they might be milked for a little more profit through re-release, and eventually sale to television, so there was at least a rudimentary attempt at preservation and storage; but once the former had made the rounds of second- and third-run theatres and drive-ins, often under multiple different titles aimed at fooling people into thinking it was something they hadn’t seen before, it wasn’t worth the expense to pay for storage … so many of these movies ended up in dumpsters.

It’s these kind of movies which Vinegar Syndrome showcase in their set. The motivating philosophy is that whatever the intrinsic value of a movie, someone went to the trouble of making it and so it deserves to be seen. While I understand the impulse, as a matter of personal taste, my engagement with the ten features included in this set was uneven. But I can’t fault the company’s efforts because no doubt there’s someone out there for whom each of these movies holds some value.

What I appreciate most is the effort itself, on full display in a documentary included in the set called Against the Grain, directed by Elijah Drenner, which provides a survey of those working to salvage these films before they rot away – along with Vinegar Syndrome’s staff, those interviewed include David Gregory of Severin and Dennis Doros and Amy Heller of Milestone Films, among others. The accounts of warehouses and storage spaces where piles of rusting film cans crusted in pigeon poop are destined for the dumpster unless some willing person shows up to claim them provides a visceral sense of how urgent this work is; and when you add in the excitement of discovering something which had been considered irretrievably lost, the process assumes an additional degree of importance. What else might be found in such a place? The missing scenes from The Magnificent Ambersons, perhaps?

It was this aspect of Lost Picture Show, the sense of discovery, the sheer hard work of restoration, which fascinated me as I made my way through the set, even as many of the movies in themselves left me vaguely frustrated or bored. But there was only one which tried my patience to the point where I gave up and fast-forwarded to the end – What’s Love (1987), which began production in the early ’70s with writer-actor-director Bill Cable, but was left unfinished until the material was picked up a decade-and-a-half later by Carlos Tobalina, who shot more material and cobbled together what we see on the disk, essentially a string of porn scene ideas stripped of the actual porn and interspersed with supposedly transgressive religious imagery. I quickly lost interest when it became obvious that it was going nowhere and just repeating the same point (about the tenuous quality of relationships) over and over again.

But What’s Love is more polished technically than most of the movies in the set, many of which have the scrappiness and rough edges of typical grindhouse fare. Not surprisingly, sex and violence run through many of them – there are sexually motivated serial killers in William Collins’s Las Vegas Strangler (1968), in which a man raised as a girl by his overbearing mother takes out his anger on showgirls; Violated (1975), which proves that Albert Zugsmith was a far better producer than director (he produced Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind [1956] and The Tarnished Angels [1957], Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man [1957] and High School Confidential [1958], and Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil 1958]); and Larry Crane’s Beware the Black Widow (1968), in which a veiled woman is knocking off members of the mob. There’s also a killer in Charles Nizet’s Voodoo Heartbeat (1973), though he’s the result of an experimental serum which supposedly extends life; this is as incompetent as Nizet’s Help Me … I’m Possessed (1974), but not as entertaining.

Three movies vie for the title of strangest in the set, and together perhaps best illustrate the weird range of material salvaged from oblivion by Vinegar Syndrome’s restoration efforts.

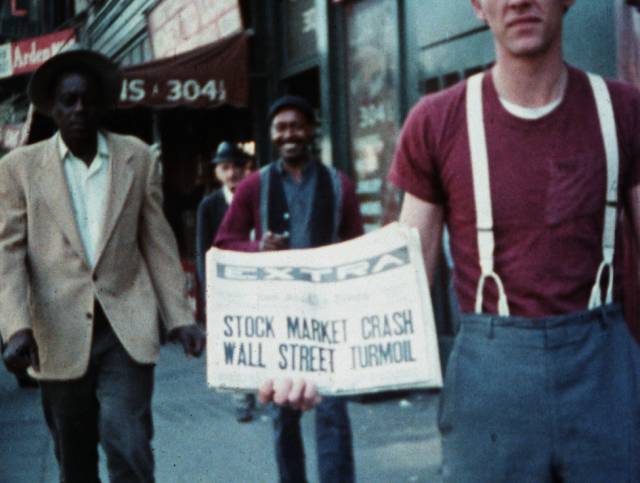

Actor Titus Moody (born Titus Moede) had a career of bit parts in movies and television in the ’50s and ’60s, became a protege of Ray Dennis Steckler and ended up mostly in porn films in the ’70s. But along the way, he tried his hand at directing, beginning with a short about bikers in 1966 (which is included here as an extra), then becoming ambitious with his feature The Last of the American Hoboes (1967), a dizzying amalgam of documentary footage and awkwardly staged re-enactments of various anecdotes about hobo life from the Depression to the present. There’s no real form or structure, a lot of footage of freight trains criss-crossing the country, stories about being treated well or badly by members of the public, railway guards, cops; of drunkenness, sickness and injury; of camaraderie and a sense of freedom which is conflated with the American myth of rugged independence. At times tedious, occasionally straining for comic effect, and sometimes quite poignant, it amounts to an impressionistic elegy to a way of life which was disappearing by the time Moody made the film.

Far off in another part of a malformed spectrum is Rare Blue Apes aka Pirates of the Cannibal Isle aka The Rare Blue Apes of the Cannibal Isle aka Mr. Quack Quack and the Rare Blue Ape (1975). I couldn’t find any information about director and co-writer Donn Greer other than that he made a string of porn movies in the half decade leading up to this bizarre musical fantasy for kids which was shot in Malaysia. If the work of Sid and Marty Krofft looks as if those guys were always stoned, then this looks as if Greer’s weed was laced with some unknown toxic substance. A young boy named Nonnie, who’s mute, has a beloved pet duck named Mr. Quack Quack. The bird irritates his parents so much that they insist it has to be gotten rid of, so Nonnie sneaks out at night, takes the duck in a small boat and sails off to a distant island populated by a band of crocodile-headed pirates called Swampies, led by Ulysses S. Krock. Captured, Nonnie is caged with an elegantly dressed Rare Blue Ape who speaks with a cultured English accent. The Ape learned his manners from his grandfather, who had been raised on an English country estate before returning to the East where he and his family maintain his impeccable manners.

Unfortunately the pirates like to eat Blue Ape, so Nonnie and his new friend break out and flee across the island pursued by the bickering humanoid reptiles. Reunited with his family, the Ape and his father manage to fight off the pirates and, having learned what family is all about, Nonnie takes Mr. Quack Quack and returns home to a warm welcome from his parents and siblings who have been worried ever since he ran away. It’s not clear whether Mr. Quack Quack will be equally welcome. The crocodile masks are all completely rigid, so the mouths don’t move when the pirates speak; the apes have a bit more animation, but the kid playing Nonnie seems completely unfazed by the weird goings-on. And did I mention that this is a musical? I can’t imagine what any kids who stumbled across this on television or at a Saturday matinee might have thought, but it’s certainly unusual.

In its own way, Red Midnight (1966) is even stranger. Made by a Massachusetts optometrist named Dr. James Newslow, it’s a “political thriller” which echoes the cheap Commie-scare movies of the ’50s. Newslow doesn’t exhibit much understanding of what it takes to make a movie, but apparently he had an axe to grind and found a very odd, roundabout way of grinding it. His concern was with the vulnerability of American cities which consisted of far too many old, wooden buildings packed close together; the risk of firestorms worried him greatly, so to make his point about the urgent need for urban renewal he concocted this story of a doctor on Cape Cod who, in helping a man injured in a water skiing accident, finds himself and his bitter wife held hostage by foreign agents who plan to set off small nukes in every major city. Although these agents have no need to say anything, they tell the doctor everything. His response, instead of trying to escape and alert the authorities, is to persuade these enemies to scrap the nukes – he doesn’t want America to become a radioactive wasteland – but instead to plant incendiary devices in every city so that their attack will clear the slums and enable the surviving population to rebuilt better and stronger.

There are obvious issues with his plan: why would the Commies want to help build a better America? And, of course, creating firestorms in every city would kill millions of people, making the doctor’s plan rather drastic. But before the night of the fiery holocaust, much time is spent on the doctor’s troubled marriage – he gets involved with the female enemy agent, while his wife plays around with one of the men. Considering the stakes, this seems like a trivial distraction. And although he has ample opportunities to alert the authorities once the agents trust him, his method for doing so – after the catastrophic fires have devastated the cities – is to grab one of the nukes, bury it on the Cape Cod beach, and phone in a warning to the FBI before triggering it. Although it wasn’t quite clear to me, I think the U.S. then retaliated with a full-on nuclear attack on Russia (this is mentioned in passing in a voice-over of the president’s speech at the end over a shot of the White House).

The set is book-ended with what are arguably the two most competently-crafted movies, both made in the context of the social upheavals of the ’60s, with a loosening of censorship going hand-in-hand with rebellion against the sexual repression of the ’50s. This was a transitional period which eventually led to the more open acceptance of pornography in the ’70s and a frankness in mainstream cinema which hadn’t been seen since the brief period between the coming of sound in the late-’20s and the imposition of the Production Code in 1934. Rooted as it was in a reaction to repression, the sense of liberation was inevitably tinged with a combination of guilt and puritanical moralizing, stemming at least in part from the tendency of exploitation from the ’30s through the mid-’60s to temper overt displays of sexuality with punishments intended to ward off moral censure.

Joseph W. Sarno is a name I’m familiar with, though Deep Inside (1968) is the first of his films I’ve actually seen. An incredibly prolific figure – more than 120 movies over four decades, frequently making six or seven in a single year – he was a hugely influential purveyor of “adult” films, dealing frankly with sexual themes and moving into overt pornography by the early ’70s. From what I’ve read, much of his work deals with middle class and suburban characters, injecting undisguised sexuality into the milieu of ’50s-style melodrama. This is certainly true of Deep Inside, which has a group of friends gathering at a beach house on Fire Island for an annual vacation reunion of women from the same college sorority.

The reunion is hosted by Millicent, a single woman whom we gradually learn enjoys manipulating everyone around her, pushing some people together while fracturing the relationships of others. There are troubled marriages, alcoholism, tentative lesbianism, all overseen by Millicent. Her puppeteering becomes increasingly extreme, to the point where she actually tries to drive one man to murder another – her motive is revealed in the final scene as sexual frigidity which fills her with jealousy and rage about other people’s lack of inhibitions.

According to Tim Lucas’s essay in the accompanying booklet, the film was probably shot in 2-4 days, which is quite remarkable. Performances are all quite good, some more than that, and although the staging is occasionally a bit stiff – characters assume tableau-like positions to deliver their dialogue – Sarno and cinematographer Bruce G. Sparks make excellent use of the Fire Island locations.

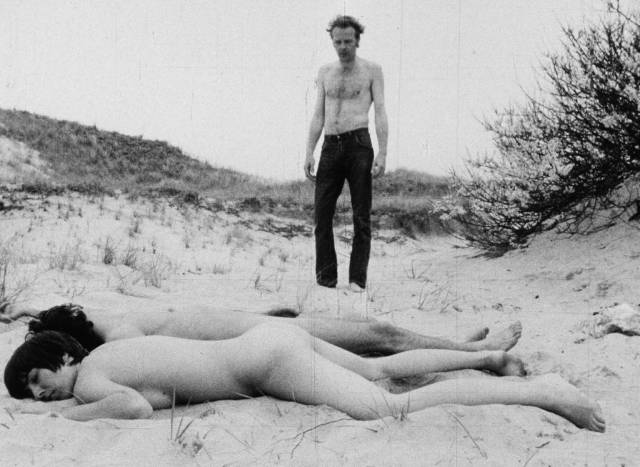

While Deep Inside adheres to a recognizable dramatic form, Walter Burns’ Barbara (1970) is more experimental, mixing almost-graphic sexual activity with documentary elements to argue aggressively for the complete overthrow of conventional sexual morality. Adapted from a novel by Frank Newman, this was Burns’ sole filmmaking credit and, like Sarno’s movie, was shot on location on Fire Island, notable since the 1920s as a haven for openly gay activity. Unlike Deep Inside, Barbara adds a gay element to its sexual activity, just one of a number of transgressive elements not usually seen in movies at the time. While the gay theme is presented positively, some of the others seem more troubling now and may well have worked against the movie’s didactic purpose at the time.

In the opening sequence, a man with binoculars spies on a couple making love in the dunes. As they fall asleep afterwards, he goes over, strips off and takes the woman from behind; she looks around sleepily, realizes that he’s not her boyfriend … then smiles and enjoys it. Then the man moves over and does the same to the boyfriend. Essentially, he rapes them both and they both enjoy it – the boyfriend later discovers his own bisexual nature because of this rape. In fact, the voyeur-rapist Max (Jack Rader, here at the beginning of a long career in movies and television) is the film’s guru, spreading the message of sexual liberation to a group of people hanging out on the island. One of his primary tools is rape, used to break down his acolytes’ inhibitions, apparently without anyone realizing that his insistence on their availability to him represents an unequal power relationship. If they resist him, they’re still enslaved to the outmoded attitudes in which society has imprisoned them.

Among the group who gather around Max to absorb his wisdom is Barbara, an underage teenager whom he initiates into the joys of sex – and who by the end, having already had sex with her brother, brings her own parents into the group, adding intimations of liberatory incest to the mix, which by now has also included a touch of bestiality with one member’s dog. The film is so overloaded with transgressions that its central argument about the harm done by society’s rules for sexual behaviour seems a little suspect, a cover for Max’s drive to dominate; made in 1970, it has troubling echoes of recent revelations about the Manson Family in the wake of the Tate-LaBianca murders.

Stylistically, there are obvious influences drawn from the New Wave and direct cinema, a raw, documentary-like camera technique, occasionally jarring editing, and a loose, improvisatory performance style. That opening sequence on the beach announces Burns’ didactic purpose by laying over the images a montage of documentary sound taken from hearings and news reports about the on-going cultural battles over sexuality and, more specifically, the depiction of sex in literature and movies. The film is his response to calls for the repression of depictions of sexual activity in media, an over-determined response with its advocacy of non-consensual sex, bisexuality, sex with minors, incest and bestiality…

*

While the value of the individual movies in the set is arguable, by packaging them together with the documentary and an assortment of contextual extras – eight commentary tracks (nothing on Rare Blue Apes or Red Midnight for some reason), brief introductions by Vinegar Syndrome staff members who were personally involved in the restorations, text essays on all the films and the issue of lost films and the problems of restoration – Vinegar Syndrome have provided an illuminating glimpse into an area of cinema history seldom addressed by the more high-profile project of rediscovery and restoration of films considered more important to that history. Most of these movies were conceived and consumed as disposable entertainment, made without any thought of posterity, but here they are. And with movies like these being given new life, perhaps there’s hope yet for even more interesting rediscoveries. As I said, if I were starting out today, this is a career I would have loved to pursue.

Comments

Kenneth,

it was very interesting to read your take on your path in life in regards to the filmworld. You’ve seen and done a lot in my estimation!

I honestly believe you could have been a professional movie reviewer as your reviews are of a very high quality. Informative and fun to read. I read the vast majority of your posts and have purchased many movies over the years, based on the strength of your reviews.

No matter what, it’s always intriguing to learn about the back story of movies and gain insights….not all genres appeal to me but most do and I appreciate the wide range of reviews that you do.

I’m always glad to hear that something I’ve written has prompted someone to watch a film I like. But I don’t think I’m cut out to be a professional reviewer – I’ve had too many annoying experiences over the years with editors who have messed with my work; at least here on my own site I don’t have to answer to anyone!

Thanks as always for the feedback.