Five things that annoy me in movies …

While watching Charles B. Griffith’s Eat My Dust! the other day, I found myself getting annoyed. Not by the sheer silliness of the film — a small-town sheriff’s son (a very young Ron Howard) steals a hot-rod to impress a girl and ends up in a cross-country chase which is merely an excuse for endless destructive mayhem – but by a minor technical issue on the soundtrack, a convention which permeates movie-making probably back to the first days of sound. Which in turn got me thinking about other conventions and practices which always irritate me when they turn up in a movie.

So here, in no particular order, are five that come immediately to mind:

One:

Why is it that sound editors habitually add squealing tires to scenes with vehicles skidding on gravel roads, dusty fields, etc? Everyone knows that tires only squeal on hard surfaces, and that they make perfectly good sounds on other surfaces which could just as easily be used when appropriate … it’s just a lazy convention used to denote “speed”, like the lazy convention used in virtually every old western that insists that every shot fired must produce a loud ricochet, even if the gun is fired where there are no rocks in sight.

Two:

Storytelling has been altered irrevocably (and not in a good way) by the advent of cell phones and the Internet. To keep a story going, drama once depended on obstacles to communication and an inability to obtain crucial information, but with everyone permanently hooked up to a network and able to Google pretty much anywhere on the planet, stories have lost a lot of their texture. In order to keep things rolling, annoyingly artificial devices must be used to get around ubiquitous connectivity — “there’s no signal”, “the battery’s dead”, “I spilled coffee on the keyboard”, etc. (The above YouTube montage posted by richfofo pretty much says it all.)

Three:

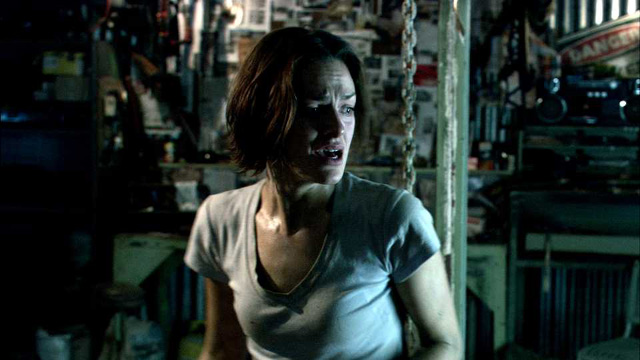

Impossible shots. Thanks to CG technology, filmmakers no longer face the physical limitations imposed by reality – the problem of placing a camera in real space and obtaining an image with real lenses interacting with real light. A virtual camera can “go” anywhere and “see” anything, but what some filmmakers fail to realize is that the brain, even if it’s just at a subliminal level, can register the fact that no such image can be obtained in reality and so the suspension of disbelief which is essential to the full enjoyment of any movie is weakened and the viewer’s investment in the story diminished. Why does David Fincher need to fly his camera through the handle of a coffeepot as it prowls through the elaborately constructed three story set of Panic Room?

Panic Room (David Fincher, 2002)

And why do the Wachowskis need to fly their camera up, down and all around, including underneath, a semi speeding on the freeway in Matrix Reloaded? They’re just showing off their flashy computer software, while actually undermining the stories they’re trying to tell.

Four:

Why is it that, in movies where people are being stalked by psycho killers, there almost inevitably comes a moment where the protagonist(s) manage to incapacitate the killer, either knocking them unconscious or apparently killing them, at which point the relieved characters turn their backs while the killer revives behind them and continues the pursuit? Why do none of these characters ever pick up the nearest heavy object and bash out the killer’s brains – or, if they’re too sensitive to resort to such violence despite the hell they’ve been put through, at least find a way to securely tie up the disabled monster so he can’t continue tormenting them? One of the worst offenders of the past few years was the over-rated Australian movie Wolf Creek in which the two women are in a barn full of large tools and heavy implements, not to mention all kinds of tackle which could be used to tie the madman up – but instead, the moment he’s been knocked unconscious, they turn their backs on him and just hang around until he wakes up and starts again.

Five:

Misuse of music. This is obviously a matter of personal taste, but when music overwhelms a movie, it undermines whatever the dramatic intentions of the filmmakers are. Sometimes this is obviously done because the drama itself is lacking and the filmmaker is trying to make the audience think that something is going on when it really isn’t. But sometimes, this “gilding the lily” ruins genuinely dramatic moments. Personally, I liked Wolfgang Petersen’s The Perfect Storm, one of those rare American films which focuses on what people actually do to make a living; the attention to detail in the work done by the boat’s crew is engrossing, but when the storm hits in the second half, you can barely hear the forces of nature, the wind and the water which threaten the crew’s lives, because all natural sounds are smothered by James Horner’s interminable, overbearing score. And I’ve never actually been able to get past the first few minutes of Joseph Losey’s generally well-regarded adaptation of L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between because the incessant tinkling piano on the soundtrack sets my nerves on end and makes me want to scream “stop!” to the point where it’s impossible to pay attention to what’s happening on screen.

Comments

How about the fake sound added to a punch, or my favourite cringe-inducing line applied to a grown woman invariably closeted in a room so she can be saved by the hero: “I’ll get the girl!” UGH.

The list is endless, of course. Another real irritant for me is the character (usually female) trying to escape/hide from the killer/monster/alien/whatever who won’t stop screaming. Surely all that noise defeats the purpose of not getting caught!