Organized crime, political corruption and bourgeois complicity: four Italian Mafia movies

Since a nearby store which accepts music and movie trade-ins for credit has greatly expanded its stock of imported Blu-rays, I’ve been acquiring more releases from Imprint and Umbrella in Australia and Radiance in England. Among the latter are a number of Italian titles which include four movies dealing with the influence of the Mafia on Sicilian society, made from the late-’60s to the mid-’70s. While the poliziotteschi which became prevalent in the ’70s were mostly focused on action and generally nihilistic violence, there was a parallel stream rooted in the entanglement of organized crime and politics, often based on actual cases and approached with a documentary style. These movies had their roots in the work of Francesco Rosi, whose Salvatore Giuliano (1962) and Hands Over the City (1963) were among the first to treat the Mafia explicitly, where before it had been veiled under layers of folklore and myth.

Damiano Damiani

Damiano Damiani’s filmography covers a number of genres including thrillers, melodrama and the spaghetti western, marking him as less of an auteur than the very political Rosi – he had followed the supernatural mystery The Witch (1966) with the politically-inflected revolutionary western A Bullet for the General (1967) and then found his enduring subject in 1968 when he adapted a novel by Sicilian author Leonardo Sciascia. The Day of the Owl began a deep attachment to Sicily and a concern for the brutal grip in which the Mafia held civil society (with the complicity of the governing authorities who benefited from the influence of organized crime over the population). This film also began a lasting collaboration with star Franco Nero, who would play very different parts in three more of Damiani’s crime films in the next six years.

The Radiance box set Cosa Nostra: Three Mafia Tales includes three of these movies – the second, Confessions of a Police Captain (1971), is missing for some reason – each of which approaches the ways in which the Mafia permeate civil society from a different angle. In The Day of the Owl (bluntly retitled Mafia in the U.S.), Nero plays Captain Bellodi, the head of the Carabinieri in a small Sicilian town, newly arrived from the North. As an outsider, he has yet to discover how things work; the local Don, Mariano Arena (Lee J. Cobb), runs everything, controlling local businesses with a mixture of threats and patronage, secure because of his ties to politicians all the way up to the government in Rome.

When the owner of a small construction company which has won a contract to build a stretch of road is murdered one morning, Bellodi’s investigation gradually exposes the intricate web of influence at the centre of which Don Mariano sits with the comfortable assurance that he’s untouchable. A key element in the investigation is the disappearance of a local man who may have witnessed the murder and the pressure applied to his wife Rosa (Claudia Cardinale) by both Bellodi and the Don. Through her, the ways in which the Mafia maintain control in the community with a mix a threats and largesse becomes clear – as well as the vulnerability of a woman in this deeply patriarchal society. (This last point becomes central in Damiani’s The Most Beautiful Wife [1970], based on an actual case in which a teenager was kidnapped and raped by a Mafioso and then pressured by the community and her own family to “restore honour” by marrying the man; when she decides instead to prosecute him, she triggers rifts throughout the community.)

Despite exposing the truth behind the murder, Bellodi is powerless to bring Don Mariano to justice and in the end he is transferred elsewhere and replaced by a new commander who better knows his place in the power structure.

In The Case is Closed: Forget It (1971), Damiani uses the tropes of the prison movie to explore the ways in which “decent” people are co-opted into supporting organized crime. Of the three films in the set, this contains the highest number of familiar elements – the prison is populated with recognizable types, occasionally manifesting as obvious stereotypes, but thanks to an excellent cast it nonetheless builds to a devastating conclusion.

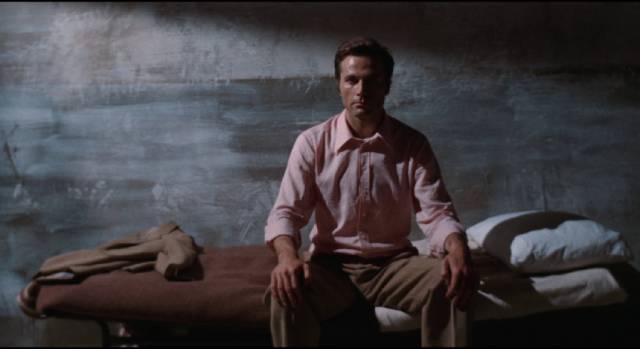

Nero is Vanzi, a respectable bourgeois architect who finds himself in prison awaiting sentencing for a hit-and-run in which a pedestrian was killed – he swears he’s innocent, but the film leaves the matter open, though it seems likely he’s guilty and refusing to take responsibility, a position which leaves him vulnerable within the society of the prison. That society, like the greater society outside, is run by powerful criminal forces in collusion with corrupt authorities. Vanzi is threatened by various low-level prisoners, but comes to the attention Salvatore Rosa (Claudio Nicastro), the highest-ranking Mafioso in the prison. With his inflated sense of superiority, Vanzi is particularly vulnerable to being manipulated with perks which end up putting him in a position of conflicted loyalties.

Having been threatened by the men who share his cell – including the psychotic Biro (John Steiner) – he manages to get transferred. One of his new cellmates is Pesenti (Riccardo Cucciolla), a deeply paranoid man who immediately suspects that Vanzi has come to kill him. Pesenti has reason to be afraid; he is scheduled to testify in a case which will expose both high-ranking criminals and authority figures whose corrupt dealings have resulted in a number of deaths. Although Vanzi eventually earns Pesenti’s trust, ironically the architect has been unknowingly incorporated into the plan to kill his cellmate – as a respectable witness who can testify that the death was suicide. The scene of the murder, with Pesenti being held down while Biro cuts his wrists with a razor in front of Vanzi, is harrowing … but Vanzi’s complicity is ensured because all he needs to do is say that he witnessed the suicide in order to have his own conviction overturned. Self-interest outweighs moral obligation to a man who had become something like a friend.

Shifting gears, Damiani’s final collaboration with Nero is a self-referential work in which a filmmaker’s political attack on a corrupt judiciary appears to be the cause of a real murder. In How to Kill a Judge (1975), Nero is Giacomo Solaris, whose latest film is a thinly-disguised indictment of State Prosecutor Traini (Marco Guglielmi), a magistrate who is involved with various political figures of dubious character. In the film, the prosecutor is assassinated and the outraged authorities try to ban it. In the middle of the scandal, Traini is found dead in his car, having been shot. Shocked by the thought that his polemical movie may have triggered an actual murder, Solaris begins his own parallel investigation, which involves him with the dead man’s widow Antonia (Françoise Fabian) as well as an assortment of politicians and criminals – “real life” reflecting the themes of his movie.

The murder triggers increasing conflicts among both politicians and Mafiosi, with the former exposing each other’s corruption and the latter settling scores with escalating violence. Much of the criticism of the film revolves around what some see as a cop out ending, though the obvious irony of the mystery’s resolution seems dramatically valid to me. Using the controversy surrounding Solaris’s movie as cover, the motive for the murder turns out to be personal – it was planned by Antonia and her lover – the ensuing political chaos conveniently obscuring the truth. When Solaris realizes what really happened, he can absolve himself by exposing the lovers, even though by doing so he undermines the power of Traini’s death to lay bare the connections between politicians and organized crime. In salving his own conscience, he renders his work as a supposedly courageous maker of crusading art impotent.

*

The Iron Prefect (Pasquale Squitieri, 1977)

Some interesting historical context to Damiani’s films is provided by Pasquale Squitieri’s Il prefetto di ferro (The Iron Prefect, 1977), based on the actual exploits of Cesare Mori, an official sent by Mussolini in 1925 to deal with the Mafia in Sicily. Given free reign to act as he sees fit, Mori (Giuliano Gemma) is something like a prototype for the rogue cops of the 1970s, though unlike Popeye Doyle, Dirty Harry and the many Italian cops inspired by them, Mori’s campaign was sanctioned by the Fascist state as he paid little heed to niceties like due process. On arrival in Palermo, one of his first acts is to visit Mafia boss Antonio Capecelatro (Rik Battaglia) and shoot him in the head. Later he lays siege to a mountain town, cutting off the water supply until Mafia boss Calogero Albanese (Francisco Rabal) and his men are forced to surrender – Albanese, who has evaded the authorities for forty years, commits suicide in shame.

Mori had opposed Fascist street thugs earlier in his career, but he eventually joined the party in 1924 and was personally appointed by Mussolini to break the hold of the Mafia over Sicily. Although sanctioned by the law, his campaign was more like a war than a legal action and he did whatever it took to defeat the organized criminals who controlled civil society. Because the Mafia’s influence was so deep, even those who were oppressed by them saw Mori as a threat to their communities – with Claudia Cardinale once again representing the deep distrust with which the Sicilians viewed the outsider. Mori was lauded in the press for breaking the Mafia, but his actions eventually came close to exposing the connections between organized crime and influential politicians, including powerful Fascists, and he was quickly “promoted” to senator by Mussolini and removed from his post as the Fascists boasted that the Mafia had been defeated.

The Iron Prefect is probably Squitieri’s finest film (made immediately after the contemporary crime movie The Climber [1975]), drawing on various cinematic influences, including the western and the poliziotteschi. Gemma gives one of his best performances, eschewing the breezy charm he typically showed in his westerns as the grimly determined Mori. The rest of the cast is equally good and Silvano Ippoliti’s cinematography makes the most of Sicily’s sun-baked landscapes. There’s also a typically fine score from Ennio Morricone.

*

Although Radiance is a relatively new company, it came out of the gate with releases which equal Indicator and Criterion in terms of quality and packaging, these Italian films being no exception. All four films look fine in 2K transfers from the original negatives, with both Italian and English dub soundtracks. The Day of the Owl is presented in both the domestic Italian cut and the slightly shorter export version. Each film in the box set gets a new interview with Nero, plus various archival interviews and new video essays. The Iron Prefect includes new and archival interviews about the historical context, the director and star, and the film’s connections with western and police movies which influenced it. And as usual with Radiance, the limited editions come with text extras – a booklet with an essay and a contemporary newspaper account for The Iron Prefect and a 120-page book of new and archival material for the Cosa Nostra box set.

Comments