The 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, part one

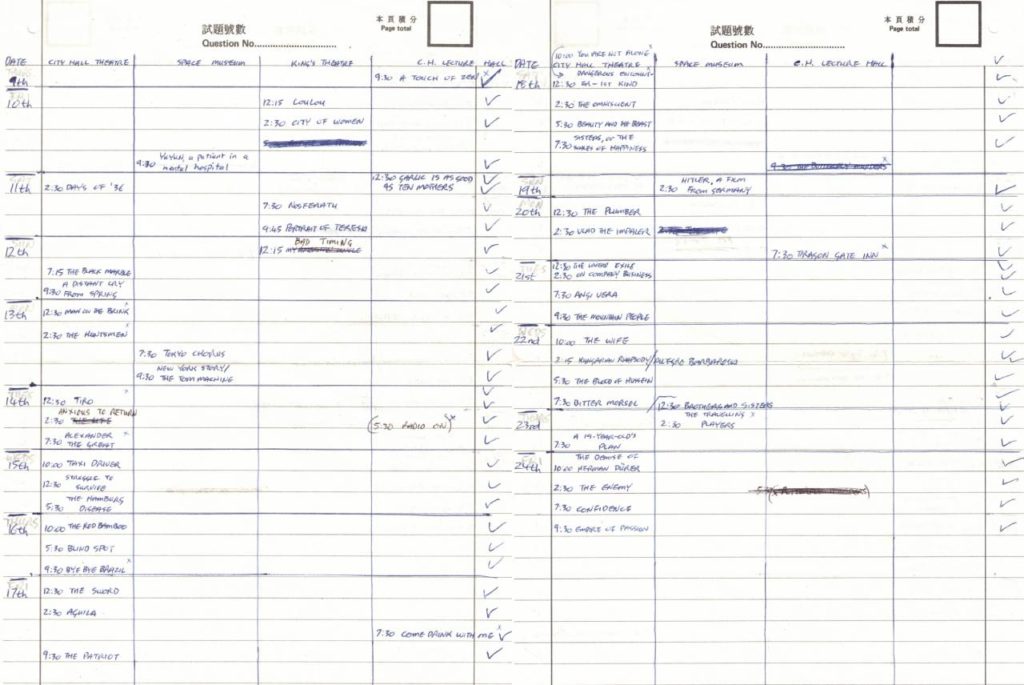

As I mentioned in my recent post about the Studio One cinema club in Hong Kong, I attended the 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival during my stay there. I saw fifty-six movies in sixteen days, a marathon I haven’t matched since, though I later went to the Toronto International Film Festival twice – in 1992 and 1998. I approached it methodically; having scoured the program ahead of time, I calculated the best way to fit as many films in every day as I could, mapped out the venues and calculated the time it would take to get from one to the next, then pre-purchased all the tickets. Every morning, I would pack snacks and drinks and head out.

Because I knew it would be exhausting and I was risking mental overload, I also carried a notebook and immediately after exiting a theatre I would quickly jot down my impressions in point form for later reference. When the festival was over, using those notes, I wrote reviews of everything I’d seen, ending up with a 56-page typed document. At the time, I’d spent a couple of years writing weekly reviews for the University of Winnipeg student newspaper, but I was still fairly unformed as a critic (though a couple of months earlier I had written my original essay about Eraserhead, so I was leaning towards more serious writing about film). I can’t say that what I wrote about the festival was any kind of coherent critical appraisal; it was essentially just my spontaneous gut reaction to the movies I’d seen.

Looking back now, as I mentioned in the Studio One post, I have no actual memory of a number of these movies, though others have stick with me quite vividly, even ones I have never had another opportunity to see. At this point, I can’t vouch for the accuracy of those memories, or for the validity of my comments about movies I’ve never seen again. But I’m sharing these 43-year-old notes here if only to call attention to some movies you’ve probably never even heard of.

I organized the notes at the time into ten categories and I’ve kept that arrangement here as a reflection of how my mind worked back then … and perhaps still does. I’ve also resisted any temptation to edit or “fix” these notes, even with those films which I’ve seen again, and perhaps written about elsewhere on the blog. For better or worse, these reviews reflect who I was when I saw these movies at the age of twenty-six.

*

I’ll start at the beginning, but won’t go through the festival in chronological sequence.

1. HONG KONG

The first film was King Hu’s A TOUCH OF ZEN, another beautifully filmed three-hour martial arts epic – in fact, the one which made him famous in the West. A naive, unambitious scholar finds himself drawn into political intrigue when his small frontier town becomes the focus of a secret power struggle. The daughter of a murdered official is in hiding and the forces of evil are closing in; the scholar joins her cause and manages to devise a strategy to help defeat her enemies (making use of the haunted reputation of an old fort). After the battle, she disappears. He tracks her to a monastery, where he’s presented with their son and sent away. But when he runs into trouble, she and some others come to help and a final fight ensues.

It begins like a period spy mystery; is quite quickly clarified into a specific political fight – then comes to a stop (his receiving of the baby is a natural ending) and then starts again, but on a mystical plane. The final fight is purely spiritual, good against evil. When evil strikes good down, good somehow rises to a new level, greater strength; and evil – faced with this – destroys itself.

There are nice touches of humour and some well-staged fights – particularly the famous bamboo forest scene. But the development lacks the smooth flow, the grace of LEGEND OF THE MOUNTAIN; this, and the greater amount of violence, make it a less satisfying film than LEGEND. Buddhism is here presented in a less ambiguous way than in RAINING IN THE MOUNTAIN (about a monastery torn by temporal political conflict).

As before, Shi Juan makes a beguiling hero and Xu Feng a marvellous heroine – there is a constant tension between her calm beauty and her calm skill in killing.

The two earlier King Hu films were both on a smaller scale. The first, COME DRINK WITH ME, was well-written, tightly directed, and well-acted. The story was simple, providing a strong good/bad conflict; an agent is sent to rescue an official held hostage by a group of bandits demanding the release of their leader. Even here, though, Hu’s fondness for ambiguity is strongly in evidence – the hero is a woman disguised as a man; the bandits are hiding in a temple where they hold drunken feasts; one of the chief villains is the Abbott who murdered his master to become leader of a sect; the hero(ine) is helped by a drunken beggar who is actually a martial arts master, holder of the staff symbolizing the leader of the sect. After the poetic beauty of Hu’s later films, the amount of violence in this film was pretty shocking – Peckinpah would have been inspired by all the gushing blood, such as wouldn’t have been permitted in an American film of the time (1966).

DRAGON GATE INN seems to be transitional; the scale of the story is much like that of COME DRINK WITH ME, but the scale of production is reaching towards the later epics. The conflict (very like that of ANGER) centres on innocents (again, the children of a murdered official) over whom two groups are fighting. There are overtones of the big spiritual battles of the later films – but the striving for something larger has made the film less taut than COME DRINK WITH ME, without actually attaining the level of lyrical epic. The gore is toned down considerably, but the fights are still well-staged – with the exception of the drawn out, curiously disappointing climactic duel with the evil eunuch; here it seems Hu’s desire for an epic spiritual conflict caused him to neglect some basic dramatic considerations – there is no emotional satisfaction in the defeat of the villain.

I saw one other martial arts film: THE SWORD, directed by Patrick Tam. A new film (though the print was in bad shape), the first feature of a TV director. It suffers from its director’s origins; it has a TV look – small scale (you never see anyone except those characters directly involved in the action), very “set-ty” – the bright plastic look of a studio. But it’s quite well-paced, though for much of its length the story seems unfocused – it’s difficult at times to know what it’s supposed to be about. There are some spectacular magic swordfights, though occasionally the elaborate choreography slips over into wasted movement and it looks a bit like a costumed disco party. The point of view is anti-heroic – its great swordsmen don’t go about doing good, they seek only to prove themselves, or live with the constant tension of knowing that others are looking for them, to prove themselves. Skill with the sword means killing, causing misery, suffering yourself…

The three other Hong Kong films were of varying quality. Hua Yihong’s STRUGGLE TO SURVIVE (CHONGPO) was uneven, episodic. Beginning with the arrival of a boatload of illegal immigrants from China – many drowning, one killed by sharks, most of the others caught by the authorities – it follows the lives of the few who make it into H.K. Their fates are fairly predictable – success for some, despair and suicide for one, others in between. In details, however, the film is often effective; the discrepancies between expectations and reality, the disillusionment of overcrowded rooms, menial jobs, relatives who greet the arrival of a newcomer with less than enthusiasm; the expectations of those left behind (“send fans, TVs, cassettes, all kinds of luxury goods”) and the struggle to fulfill those expectations, to earn enough to send something back from the golden land, to uphold the dream; trying to maintain some kind of group identity based on their one shared experience even as their lives go off in different directions. There’s a fairly good mix of comedy and drama, but overall it looks like a low-budget rush job.

But it’s a bit better photographed than MAN ON THE BRINK, though the latter is a better film in most respects. Directed by Alex Cheung, MAN is rough but effective. A young cop is sent underground to infiltrate a triad. The disintegration of his life – and of his personality – is convincing (handled more clearly and with less pretension than Friedkin’s CRUISING). The more he participates in gang activities, the more he has to push away his old ties, the less certain he is of his old identity, of why he became a policeman in the first place (he wanted to be a hero). He’s dismissed from the force after himself planning a robbery, goes into further decline, then tries for a come-back, tipping off his old superior about a raid. The ending is strong, violent, and convincing: though helping the police, he’s perceived as a robber and beaten to death by a crowd of angry civilians. The police are seen in a very ambiguous, generally uncomplimentary light; sending men out to participate in crimes, harassing and arresting old women hawkers, etc. For all its rough edges and unpolished narrative, the film succeeds quite well.

Tsui Hark’s DANGEROUS ENCOUNTER–lst KIND is the most polished, technically proficient Hong Kong-made film I’ve seen. It’s also one of the nastiest, most vicious films I’ve seen. It presents a problem: about violence, it seems to go too far, wallowing in the violence it’s dealing with. But that seems intentional – almost as if the film is shitting on the audience’s lust for gore. The film becomes inseparable from the problem with which it deals. Having said which, I must go on to say that it’s one of the most gut-wrenchingly tense and exciting films I’ve ever seen. As a story-teller Hark is a match for any slick action director from the U.S. – and the film has depths seldom encountered in this kind of filmmaking in North America. Three teenage boys out for a joyride hit-and-run a man; they’re seen by a girl – the unbalanced sister of a policeman who blackmails them into joining her dangerous pranks. A chance encounter results in their getting hold of a bag full of Japanese bank drafts. Trying to cash these gets them tangled with a triad – and then with the real owners, an international group of Vietnam vets involved in some vast unspecified dealings (arms are involved). The film climaxes in a bloodbath which leaves only one person alive – one of the boys, now somewhat crazy – and which leaves the viewer literally shaking. Hark is determined to push the thrill-seeking audience beyond even its capacity to tolerate violence. Along the way there are brutal murders, torture, mutilation – watching it is rather like being put in the place of Alex in A CLOCKWORK ORANGE. Unfortunately there is also some very real cruelty to animals which gave me a very negative disposition towards Hark despite his skills. But that aside (not that it can be ignored), it’s a shockingly effective film, a vicious black comedy about escalating violence; beginning with nasty kids’ pranks, it expands through ever-widening circles of violence which go far beyond anybody’s ability to control it. And how easily those kids slide from each circle into the next. The strange thing is that the warning is so skilfully embodied in a story which continually provides the visceral shocks the kids in the film are searching for … and ultimately terrified by.

Comments