The 5th Hong Kong International Film Festival, part six

Part six of my notes from the 1981 Hong Kong International Film Festival… and as always I haven’t edited these reviews in any way, although in some cases I no longer agree with what I wrote back then.

6. EASTERN EUROPE

Doru Nastase’s VLAD TEPES (VLAD THE IMPALER, or THE TRUE LIFE OF DRACULA) is an elaborately mounted but confusing Romanian epic – though much of the confusion could result from some forty minutes being cut from its original running time. The endless intrigues – and the numerous factions involved in them – are difficult to follow as Romania struggles to achieve some kind of individual national identity in a turbulent 15th century Eastern Europe threatened by invading Turks and greedy princes. And the film certainly fails to achieve its main objective: the redemption of Vlad from his infamous image. At the end there is no sense of a country changed for the better – the factions still fight amongst themselves, making the place vulnerable to outside forces. He did bring down the crime rate, certainly – but not by improving the conditions which gave rise to crime, not by creating a “just society”; his method was the simple and direct application of terror to any wrongdoer – or anyone who happened to cross him. Nastase’s direction isn’t very imaginative, lumbering along, devoid of dramatic highs – but some of the acting is good. The ending is abrupt and unsatisfactory.

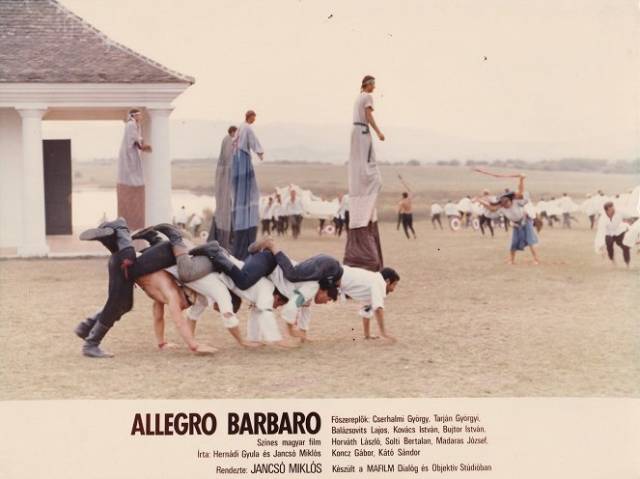

And what can one say of HUNGARIAN RHAPSODY and ALLEGRO BARBARO, the first two parts of a trilogy by Miklós Jancsó? This retelling of the revolutionary history of Hungary is so relentlessly artificial, so pretentious, so ludicrous that the only response it elicits (apart from boredom) is exasperation. How could so much visual beauty be squandered on such numbing rubbish? But of course that’s just my opinion – Jancsó is highly esteemed in Europe, I believe, for his method of compressing whole facets of history into a single formal movement (of course, he has to scrap such unnecessary elements as the traditional dramatic scene – not to mention plot – and character….). And formal is the word. The whole thing is carefully choreographed – the central figures, the massed extras, complex camera moves all blended together into a single elaborate movement. The first film is so stately and formal that it allows absolutely no sense of involvement – Jancsó wants to make sure early that you know these figures aren’t anything so mundane as human characters. There are no emotional shifts as the film moves between the formally staged decadent revels of the bourgeoisie and the formal movements of battle. The whole thing is supposed to symbolize an inner struggle – Istvan Zsadanyi’s “schizophrenia”; not an illness, but a conflict between his aristocratic received ideas and the truths of communism. He’s cured by a revelation of those truths and his resulting identification with the peasantry.

The second film is more problematic – not to mention worse, even more phony than the first. It continues on from the first, but in a seemingly constant haze of blowing smoke (an incredibly intrusive, annoying effect). Here we have a joyous peasant commune presided over by Istvan – ever so joyous; nobody works, they just parade and cavort in revels remarkably like those of the first film’s bourgeoisie (complete with the same nudes on the lawns).

Both films are full of movement, endless exhausting movement, but no action. Maybe all those choreographed masses do symbolize different historical events – but in terms of drama, it’s all dead and pointless. I know: Jancsó would object that he’s not trying for ordinary drama – no doubt he’s trying to impose the forms and structures of music to film. The transplant doesn’t take, and the patient doesn’t survive. And it’s definitely not a proletarian work. So utterly stylized and “intellectual”. You need annotations to work it all out – but it’s so tedious and uninvolving, it’s not worth the bother. Even the satire on the bourgeoisie with which it begins is humourless and staged without feeling. But, god, it’s superbly photographed, loaded to the hilt with stunning images. What a waste.

The other two Hungarian films I saw took an approach totally different from Jancsó’s – both were realistic and both focused on, and examined in detail, individual characters. And both were vastly better as films than Jancsó’s claptrap.

Pál Gábor’s ANGI VERA is a small, subtle, and moving film about the conflicts which arise inside people when they are moulded into some official, uniform shape. A decent, outspoken young woman becomes noticed when she stands up and points out the appalling conditions in the hospital where she works (in 1948). She is sent to a Party education centre where the chosen are taught the meaning of the revolution and equipped to carry on the work. Sort of. During the course, ideology is used to replace personal feelings, individual thought and conviction. The moral decency which Vera so innocently expressed (and which got her noticed) has nothing to do with it – in fact, it may become an obstacle to unquestioning acceptance of the Party line. The technique used at the school is subtle and brutal: the inhabitants are separated from each other by fear and distrust, taught to spy on each other, report each other for incorrect thought and behaviour – so in the end there’s only one refuge left: the Party. Poor Vera is too innocent; she tries her best. For a brief moment, she falls in love with one of her teachers, a married man. This divides her loyalty; she feels guilty about it. And during a session of self-criticism – a barbaric device for stripping away psychological defences – while others reluctantly speak the required platitudes, or remain sullenly silent as their “faults” are read out, going only through the official motions, aware that hypocrisy is at the core of the system, Vera genuinely confesses – to the shock of officials, and to the disgust of her fellow students, who see it as a betrayal, a breach of their best line of defence, their ability to keep genuine personal truths to themselves. In her the system has worked too well; the shock derives from the revelation that she has replaced personal feeling and conviction with the official line; her old decency has been corrupted into the unreal “morality” of the Party; she even falsifies her confession somewhat to conform more closely to what she thinks is expected of her. Yet despite the compromise of her decency, the act propels her to the top of the class. The better she becomes as a “revolutionary”, the more confused her values become – but she is the type of person who rises in the system as it is. I have read that Gábor intended the film to be about an opportunist – if so, he failed; Vera comes across as a victim, a decent woman twisted into the.opposite of what she naturally is. As the teacher is a victim of the system through her. As the older fellow student is a victim – once a dedicated revolutionary fighter, her convictions now no longer of the narrowly accepted kind, she now bitterly throws herself into the work; informing, spouting the official line, taking Vera under her wing and guiding the destruction of her old naive decency…. It’s a sad, moving film, quietly subversive (while it exposes the workings of a discredited period, it implies that those who reached power and shaped the nation were people like Angi Vera – thus it has a pretty shabby foundation), beautifully made, and beautifully acted.

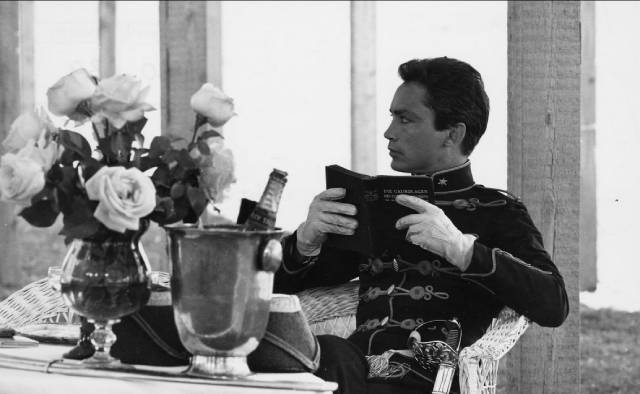

Even better was István Szabó’s CONFIDENCE, a superb, highly compressed study of two people in an enforced relationship. Two resistance fighters (actually one resistance fighter and the wife of another) are forced to act as man and wife towards the end of the war. They have never even met before, now they must live in close contact in a rented room, forced to play parts and to trust each other not to betray each other. There are conflicts between their real selves from their outside lives and the selves they must assume. Gradually this enforced relationship takes on feelings and behaviours appropriate to a real marriage (to a point where contact with the real husband and wife is seen as a kind of betrayal). The tensions are handled in minute and intricate detail. It’s a harrowing, superbly acted analysis of the way fear acts on the way people view each other – drawing them together, but at the same time holding a wall of distrust up between them. True confidence only comes after they’ve been parted at the end of the war – when it’s too late. They finally come to believe in their relationship after it’s been torn apart just like their original marriages at the beginning. It’s a tense, sad film which gets almost too close to its characters for comfort.

My favourite among the Eastern European films was Juraj Herz’ BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (aka THE VIRGIN AND THE MONSTER) from Czechoslovakia. A sumptuous version of the fairy tale filmed on location at still-extant medieval sites. Neither prettily prissy like a Disney cartoon nor a parody – not even tongue-in-cheek – Herz approaches it with a realistic style and a deeply romantic sensibility. Shot in colours as dark and rich as a Northern Renaissance painting, the story is told with beautiful simplicity: a merchant loses everything when his wagon train of goods vanishes in a dark forest (it gets lost taking a short cut, up to its knees in mud – the road is blocked – something is glimpsed through the foliage – the men panic, the wagons roll into a ravine – everyone is killed – lastly a young woman, savagely slashed by that something). Ruined, he goes off in search of the wagons. Finds a ruined manor, in which he discovers masses of precious jewels. A voice gives them to him – but when he plucks a rose from a branch, the voice says he must return to the manor or send someone in his place – to stay forever. Needless to say, his greedy, selfish older daughter won’t hear of it – but the lovely young Beauty slips out and rides to the forest. Gradually she falls in love with the voice, but she wearies of never seeing its owner. When she finally does look, she flees in horror back to her father. But she can feel the Beast pining away – realizes that his appearance doesn’t change what she knows about his nature. She returns to him – and he becomes human and mortal through her love. The psychological meaning is there to be seen – the slow awakening of sex, leaving the father, fear of sex, finally the acceptance of adulthood with its awareness of mortality – but Herz hasn’t made the film as a psychological interpretation; his concern is to tell the story as purely as possible. The settings are gorgeous; the dark forest with its bare twisted branches, tangled bushes, and muddy tracks; the house which is like a living, festering corpse (absence of mortality is also an absence of true life) which gradually becomes rich and beautiful as Beauty’s fear diminishes and she grows closer to the Beast, making him feel more and more human. The Beast itself is superb, a marvellous bird-like predator, devourer of virgins’ blood until tamed by Beauty and taught to love. The film restores to the cinematic fairy tale the violence which balances out the beauty, real death to balance out the discovery of life.

Comments