Guest post: William K. Everson & British Film

When my friend Howard Curle offered to write a guest post for my blog, I was happy to accept. Howard has taught film here in Winnipeg for many years, initially at the University of Manitoba and now at the University of Winnipeg, and we occasionally get together to watch and discuss movies from my collection (most recently Leonce Perret’s interesting 1913 feature L’enfant de Paris). Although our backgrounds differ, we both share an enthusiasm for British film, and here Howard offers an account of where he obtained that enthusiasm. –K. George Godwin

What I learned about British films from Bill Everson

By Howard Curle

In his book-length 1968 interview with Alfred Hitchcock, director Francois Truffaut provocatively stated that the terms “cinema” and “Britain” were incompatible. He based his opinion on the perception that the English preference for a subdued way of life with its stolid routine was essentially antidramatic and “in conflict with plastic stylisation.” Putting aside the argument that Truffaut was then 37 and should have known better, there were at the time writers who considered English cinema quite vital, thank you, or, if they admitted a strain of stolid routine, thought it quite interesting: Raymond Durgnat, for instance. But among even older enthusiasts, William (“Bill”) K. Everson should also be singled out. Although he wrote no book comparable to Durgnat’s A Mirror for England, he included positive assessments of several British films in his book Love in the Film and wrote scores of programme notes for British movies for film series he organized throughout his professional life.

Everson was my teacher when I was a graduate student at New York University and in the following notes I hope I can evoke some of the flavour of his course on British movies which I attended in 1978.

Everson was 48 at the time; to me he looked a bit older. He had a low but gentle voice; he was avuncular in appearance with a reticence that differentiated him from my other teachers who were American-born. He reminded me of the British character actor Geoffrey Keen who, dressed in a regulation suit and tie and sitting behind a desk in numerous British movies, let a number of attentive younger chaps know what was up and about. Everson was like that: his knowledge derived from experience. By 1978 that experience was considerable: a theatre manager after his British army term, publicity department for Monogram (later Allied Artists) after emigrating to the US in 1950 (just 21 years old), and then work as a freelance publicist and programmer. All this time Everson had been collecting films: 35mm and 16mm prints of titles discarded from distribution warehouses and libraries.

It was from his own collection of 16mm prints that the films seen in class were chosen and his lecture notes were derived. Everson was particularly good on the backgrounds of directors, actors and cinematographers with whom we were unfamiliar but whose work was often trans-Atlantic, for instance that of directors William K. Howard, Bernard Vorhaus, Roy William Neill and Robert Stevenson. Everson took questions with enthusiasm but he was not one to probe aesthetic or theoretical issues too deeply. Nevertheless, his structuring of the course was rigorous and the films themselves certainly not antidramatic nor lacking in cinematic expression.

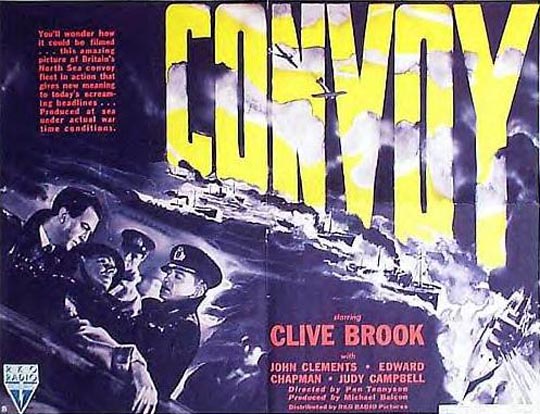

Everson divided the term into short periods when national or industry circumstances (the war, the years of economic austerity that followed 1945, the influence of American-influenced consumerism) had a direct or indirect effect on the films English studios made. Take for instance the first period from 1939 to 1944: films about the war effort, both documentary-influenced fiction features and short propaganda films, predominate. Everson pointed to the German influence in Michael Powell’s 1940 The Spy in Black (Conrad Veidt’s Captain Hardt boarding a ferry-boat Nosferatu-like in a dark cloak) and singled out Powell’s early use of Valerie Hobson as an English girl able to rebuke both the advances of Veidt and the social obligations of a minister and his wife. A more orthodox early war film was Convoy (also 1940), directed by Pen Tennyson (great-grandson of the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson), who died aged just 28 the next year serving his country. An early Ealing film, a studio whose style we would examine ever more closely as the course proceeded, Convoy was a class-bound ship-in-peril story that anticipates the better known In Which We Serve from 1942.

Everson was an all-inclusionist in collecting and screening; the English version of Henri Langlois of the Cinematheque Francaise who believed that every film deserves a showing. For instance, we looked at short propaganda films such as All Hands (John Paddy Carstairs, 1940), with John Mills as a sailor who inadvertently passes information to the enemy through teashop conversation with his girlfriend. The film is blunt: Mills’ ship is sunk; the young sailor drowned. Back in the teashop, the girlfriend is hurt but puzzled; the elderly Nazi agent who works behind the counter wears a look of contentment.

Inspired by Everson’s eclectic choices – which sometimes meant screening just extracts so that we could sift through reels of material – I decided to spend some time in the reference room of NYU’s Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, copying from Dennis Gifford’s British Film Catalogue the titles and directors for each year from 1939, ranking the titles the way Andrew Sarris had done in The American Cinema. (I concur with Dave Kehr in the preface to his just-published Movies When They Mattered that our generation of cineastes carried Sarris’s book everywhere we went and read it diligently like catechism.) I glanced as well at Movie magazine’s director rankings from their May 1962 issue (from the reprint in Movie Reader). This way lay madness no doubt but as an inveterate list maker, I rationalized the process by calling it research for a possible essay (or blog, as it turns out).

The lists revealed prolific but obscure directors (George King, Marcel Varnel, Herbert Mason) and confirmed trends Everson introduced in his lectures. (We screened a George King in class, A Face at the Window [1939], an undiluted Victorian melodrama with villainous cackles and hair-breadth escapes left intact. The film starred the deliriously hambone actor Tod Slaughter who, Everson noted, essentially supervised production.) The resulting chronology gave me a broad albeit superficial portrait of a given year, one that could gradually be fleshed out with notes through classroom screenings, the occasional retrospective at the Bleeker Street cinema just a couple of blocks from the university, or at the very least, read about in Durgnat or back issues of films and filming magazine. Such was the methodology of a film studies student in the days before the internet.

A particularly strong film from Everson’s class was Millions Like Us, a home front drama from 1943 written and directed by Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat. This film was particularly good on the details of war-time life: a father coming home from home guard duty to a kitchen sink of dirty dishes, young men piling into factory-sponsored dances, the boyfriend who for security reasons can’t tell where he was the previous night, a brief honeymoon at the beach, now bombed and deserted. With its multiple storylines, Millions Like Us resembles John Schlesinger’s Yanks, made the year after I completed Everson’s course, a film I appreciated, not least for the way Lisa Eichhorn was able to convey the qualities of both Phyllis Calvert and Patricia Roc from the earlier film. Like George Orwell’s As I Please columns for the Tribune, like J. B. Priestley’s wartime broadcasts, Millions Like Us conveys an intimate and poignant picture of English life. It offers an unqualified positive image of the English crowd and perhaps expresses better than an essay could why Britain voted Labour after the conflict ended.

To be continued …

New York University has set up a fascinating website devoted to Everson which includes what appears to be an inexhaustible archive of his typewritten notes about individual films, a photo gallery, and a rich collection of publicity materials for hundreds of movies.

Comments

After reading your post, I immediately went on YouTube to watch as much of Millions Like Us as I could. I loved its ‘documentary’ compositions–the fluid, gentle camera–and couldn’t help wondering where this picture has been hiding. But obviously that was Everson’s point: overlooked movies often possess surprising strengths. The only Everson book in my collection is The Western: From Silents to the Seventies, co-written with George N. Fenin, a book that lives up to Everson’s credo that “every film deserves a showing”, even going so far as to indicate post-war nuances in Wild Bill Elliott westerns. Your comment on the methodology of film students in the days before Internet, (hunting through back issues of Film and Filming) reminded me that, back then, knowing about a film, reading about it, was often as close as one could get to the real thing. Thank you, Howard, for these recollections of Everson’s work as a teacher.