David Lynch 1946-2025: a very personal loss

Words are inadequate…

I learned of David Lynch’s death on January 15 when I received a sudden flurry of emails and texts from friends and acquaintances the following morning. The news spread quickly on-line through news outlets and social media. There was a sense that something monumental had occurred – something much more than just another celebrity death. David Lynch was a cultural phenomenon, somehow distinct and apart from mainstream American cinema and yet hugely influential through more than four decades during which he made strange, baffling, deeply personal movies which connected with a large, devoted audience despite not adhering to the rules of the Hollywood industry.

The news wasn’t unexpected – word of his severe emphysema had become more widely known last year – but it still came as a shock. For me, this has a more personal dimension because of the part David and his work have played in my life. It still feels unreal, though it began forty-five years ago when I saw Eraserhead for the first time. For some reason, his first feature connected with me in a way I don’t fully understand even now, a way unlike any other movie no matter how great or engaging. While the film left many people cold, even repulsed, it held a strange fascination for me – yes, the imaginary world it evoked was disturbing, even ugly, yet it drew me in and inhabited my subconscious in some ineffable way. From whatever depths in David’s own mind it had emerged, it somehow felt like my own dream. Sitting in the darkened theatre, I felt alone with thoughts and feelings I couldn’t quite grasp, although my need to understand had an urgency which drew me back repeatedly as the film returned regularly to Winnipeg as a midnight movie through the summer of 1980.

In some sixty-five years of movie-going I’ve seen many films which have had a powerful effect on me – great works of art and potent pieces of popular entertainment – but nothing else has gotten under my skin the way Eraserhead did. There was something in David Lynch which spoke to me directly, but in an unsettling, subliminal way. Although I had been writing movie reviews for a couple of years by then (for the University of Winnipeg student paper), my opinions were fairly superficial. But Eraserhead compelled me to dig much deeper; for the first time I needed to work out not only what the movie was saying, but also how its meaning was constructed and conveyed. This was not straightforward or easy to parse, because watching the film was like dreaming – not like dreams as they are usually portrayed in movies, with rather obvious symbolic meanings, but like an actual dream with all its mysterious, inexplicable connections and leaps of logic. As everyone knows, trying to explain a dream is futile because they defy logical explanation.

And yet, months after last seeing the film, I managed to reconstruct it on paper, recalling with surprising accuracy the sequence of events and the details of their expression, and proceeded to tease out what seemed to be a coherent pattern of meanings. I had never analyzed a movie in that much detail before, and have not done so with any other movie since. And as with any attempt to explain a dream, the effort in a way killed the object of my obsessive attention. My interpretation was coherent and plausible as far as it went, but it pinned the dream down and took the life and vitality out of it.

Which is where it might have ended if my essay hadn’t found its way into David’s hands. Apparently Eraserhead wasn’t actually done with me yet. He liked what I had written, partly because no one else at that time had made such a concerted effort to understand his film, and he agreed to cooperate with the writing of an article about the four-and-a-half year effort to create the film. There still seems to be a fairytale quality to the experience; his labour of love had called to me and an unexpected series of circumstances led me to him. This still seems remarkable to me – I was essentially nobody at the time and yet David had hand-picked me to be the person to whom he would first tell the story of the making of Eraserhead because he recognized the deep personal connection I had to his film.

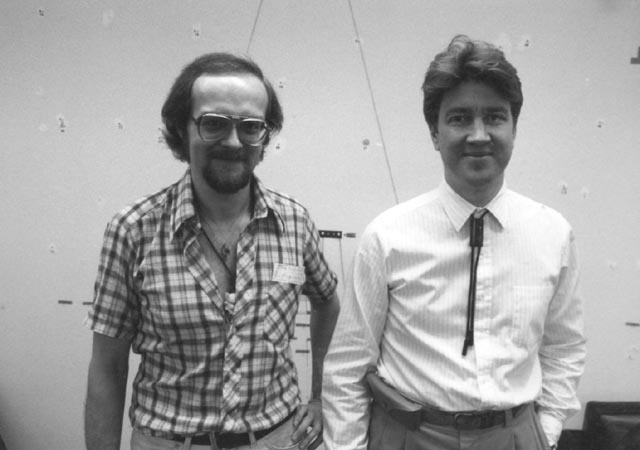

I honestly had no idea what I was doing. I had never interviewed anyone before, had no journalistic experience, yet I spent a week in Los Angeles in December 1981 interviewing him and many of his collaborators, recording a detailed, multi-faceted account of the lengthy process of creating his singular first feature.

It would be a gross understatement to say that I was nervous and felt intimidated when I arrived on the Universal lot just after lunch on Tuesday, December 8, 1981. No doubt journalists who cover the industry take it in stride, but until then the people who made the movies I watched were a distant abstraction. And here I was, about to meet the man who had made a film which had affected me more deeply than any other. I had my cheap tape recorder and a notebook in which I had listed all the points I could think of to ask him about, but I couldn’t help imagining that I was about to make a colossal fool of myself.

But when David’s assistant Steve Martin led me into the office I found myself facing a young, friendly man who shook my hand and smiled, immediately putting me at ease. Despite what I had read about his reluctance to talk about himself and his work, what followed was a surprisingly relaxed three-hour conversation – while I did ask many of the questions I had, for the most part all I needed to do was occasionally prompt and, taking my cue, he would talk at length, providing far more than I had any expectation of hearing. Certainly there were some specific things he withheld – as expected, he wouldn’t talk about particular technical details (especially the baby in Eraserhead) or the sources of specific ideas, although the latter clearly emerged organically from the process of creation – but he was otherwise very open to discussing his experiences and the ways in which his work drew on and was shaped by those experiences.

As we talked, I quickly forgot the sense of intimidation with which I’d entered the room. As so many have noted, David was surprisingly down-to-earth considering the strangeness and intensity of his work; the man who had conceived of Eraserhead and spent four-and-a-half years holding together a cast and crew through numerous difficulties while maintaining an unwavering creative focus took enormous pleasure in seemingly trivial and mundane things – like his daily lunch at Bob’s Big Boy. I had never met anyone like him (and wouldn’t meet another in the decades which followed). He gave the impression of being happy and relaxed, constantly fascinated by all the details of existence which surrounded him while deep inside strange and frequently very dark things bubbled up from his subconscious and took shape in his films, in his art, and later in his music.

He himself attributed taking up Transcendental Meditation during the years working on Eraserhead for the balance he had achieved between these internal and external realities, allowing the darkness to emerge without overwhelming the light. While many have come away from his films with an impression of the darkness being dominant, this may say more about the viewer than the filmmaker. It doesn’t fully acknowledge the humour which runs through much of his work or the warmth and empathy with which he views so many of the characters in his films. Strangely, this side of his personality, the person I experienced in my own interactions with him, was represented most openly in a film which many of his fans seemed to consider a disappointing anomaly – The Straight Story (1999). Anyone wanting to know what he was like in person need only watch this luminous film (and perhaps also John Carroll Lynch’s Lucky [2017], in which he essentially plays himself as Harry Dean Stanton’s friend Howard).

Although I may not have realized it at the time, my two afternoons spent in conversation with David were transformative because he spoke to me as an equal; there was no condescension, he treated every question I asked and opinion I offered seriously and I quickly forgot any thoughts of differences in status. He might be famous (earlier that year he had received multiple Oscar nominations for The Elephant Man [1980]), but there was no sign of ego, just openness and generosity.

It was this impression which gave me the courage the following spring to approach him about the possibility of getting work of some kind on Dune. This was absurd on its face as I had no qualifications or experience in film production and yet he didn’t brush me off; I wasn’t hopeful, but he said he’d keep me in mind and much to my surprise contacted me twice during 1982 with potential opportunities. I can no longer recall what those might have been, but in early 1983, as pre-production was gearing up with the shoot scheduled over the summer in Mexico City, he contacted me again and this time it was to tell me that I did indeed have a job on the production.

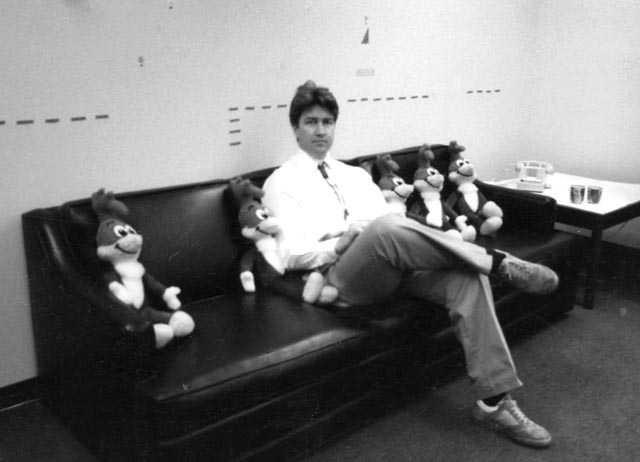

This still seems utterly unreal to me. The Vice President of Publicity, Promotions and Advertising at Universal had come up with the idea of having a documentary crew attached to the production for the duration of principal photography, something previously unheard of, and David responded by saying that he would only agree if the crew consisted of people he trusted; he told them that they’d have to hire a cameraman he knew from the AFI, Anatol Pacanowsky, and this writer from Canada. And that’s what they did. I got to work for six months on one of the biggest movies made up to that time, despite having absolutely no qualifications, because David told the studio to hire me based on our meetings more than a year earlier and the fact that he liked the article I wrote about him and Eraserhead.

Through all the stresses and work of putting the Dune production together in 1982, David had kept me in mind, which still seems like a remarkable act of generosity. My experiences in Mexico, watching him struggle to make something personal out of the industrial behemoth of Dune, maintaining humour and grace in the face of the demands of a studio and producer who, having hired him for his distinctive artistic voice, fought to rein in his creative idiosyncrasies through what became a gruelling, dispiriting six months, only reinforced my impressions from those first meetings in his office. Even in the midst of those struggles, he remained open and generous.

Meeting David Lynch was the most transformative event in my life. While we only had intermittent contact after that summer in Mexico, with the release of each new film, that connection has been revived. Although none have had quite the same impact as my first encounter with Eraserhead, each one has brought back a vivid sense of the remarkable man I met in December 1981 and the way he changed my life in entirely unexpected ways. Although I can’t quantify those effects, I know I wouldn’t be the person I am today if I had never met David, and for that I am deeply grateful.

Comments

I was demoralized when I heard of David’s death. I remembered the effect his movies had on me, especially when I saw them at the cinema. The Elephant man was eye-opening… but I was most deeply affected by watching Blue Velvet at my local cinema. Surreal and mesmerizing at the same time.

I have most of his movies and tv shows in my collection. He will be deeply missed….thanks for writing about your experiences with him!