Donald Cammell & Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970): Criterion Blu-ray review

Performance (1970), conceived by the painter Donald Cammell (who had given up painting) and photographed by Nicolas Roeg, one of Britain’s foremost cinematographers, who was on the verge of giving up cinematography for directing, was both very much of its time and very much ahead of its time. Co-directed by Cammell and Roeg, in both content and technique it confounded audiences, critics and – most troublesome – its American backers, and yet it has come to stand as one of the signature films of the chaotic social upheavals of the late ’60s (it was shot during that most revolutionary year 1968, though its release was held up for two years by Warner Brothers, who didn’t know what to do with it).

Conceived and produced in a time of radical change, Performance was an abrasive, baffling assault on its potential audience. Having received funding largely on the prospect of attracting a youthful audience because it was to star Mick Jagger, who was at the height of counterculture celebrity, its rejection of conventional narrative and classical style initially pleased almost no one. Even today, fifty-five years after its original release, it remains aggressively confrontational, its innovative visual style and radical editing challenging expectations. And thematically, its focus on shifting definitions of sexuality and gender make it seem even more pertinent today than it appeared to a contemporary audience at the beginning of the ’70s.

The film’s exploration of identity and its mutability wasn’t without precedent. A couple of years earlier, Ingmar Bergman had made Persona (1966), in which two women gradually merge into a shared identity; and a few years before that, perhaps more pertinently, Performance’s co-star James Fox had co-starred in Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963), in which issues of class and sexuality are entangled in the power struggle between two men in a London townhouse. What distinguishes Performance, though, is the way it pushes the boundaries of cinematic representation in its depiction of class, sexuality and the context of social destabilization out of which it emerged.

And yet superficially Performance has a rather simple, although bifurcated, narrative. Chas (Fox) is an enforcer for an East End gangster named Harry Flowers (Johnny Shannon). He loves his work, perhaps a little too much. After a messy encounter in which he kills a bookie, he needs to hide out for a few days while awaiting an opportunity to get out of the country. By chance, he finds a basement room in a rundown mansion in Notting Hill which belongs to a reclusive pop star named Turner (Jagger), who struggles with the thought that his creativity is exhausted. Spending his days indulging in sex and drugs with two women, Pherber (Anita Pallenberg) and Lucy (Michele Breton), Turner initially tries to kick Chas out, but is gradually drawn to his aura of violence, while Chas finds himself sucked into the hothouse atmosphere of decadence to the point where he all but forgets the urgency of his need to escape.

Onto this narrative frame, Cammell’s script adds multiple thematic layers while Roeg’s camera finds expressive ways to instill meaning into every moment, all of which is energized by an editing style which compresses those moments into a constant flow of evocative fragments which are disorienting and steeped in a subversive deconstruction of social and sexual conventions.

Each of the two worlds within which the story takes place has its own tone and energy – the first half set in the London underworld draws on characters and events much in the press at the time, particularly the crimes of the Kray brothers, steeped in the casual violence which drives the illicit business enterprises of Harry Flowers; the second half, however, is turned inward towards a decadent aesthetics of personal expression through creativity and physical gratification. The world of the gangsters is modern, and like all gangster films to some degree lays bare the crude violence of capitalist self-interest, while the world of Turner’s mansion reflects the feverish aesthetics of fin-de-siècle Decadence – Turner bridges the gap between Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Grey and the excesses of modern celebrity.

Bringing these two worlds together, Cammell explores the classic theme of the doppelganger in which one character is split in two, each part expressing aspects initially hidden from the other until, as is often the case, the darker overwhelms the lighter. The question here may well be which is the darker? Turner is drawn to Chas’s violence as a means of reigniting his own creative impulses, while Chas’s violence is gradually exposed as an extreme strategy to suppress a part of himself he fears. To oversimplify, Chas asserts a hyper-masculinity to deny feminine aspects of his personality, while Turner leans into the feminine to conceal his own potential for violence.

The gender fluidity on display is the film’s most prescient aspect, drawing on Jagger’s own androgynous presence (in the central sexual sequence, as Chas is transformed into a female image of himself, Jagger and Breton morph into each other in bed with Chas). This non-binary charge bleeds back into the gangster milieu during Jagger’s performance of “Memo From Turner”, during which he replaces Harry Flowers as the gang boss and exposes the gay subtext of the gangsters’ masculine bonding (again, referencing the Krays).

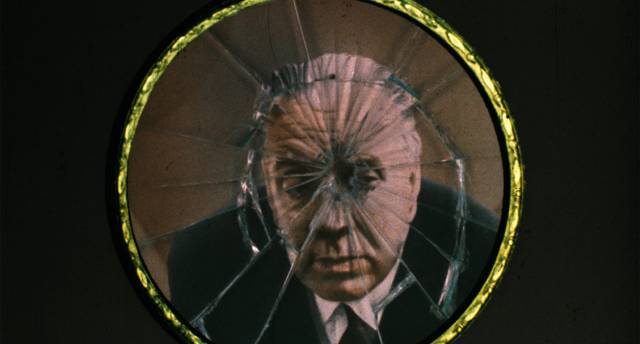

The ending of the film remains enigmatic and to a degree indecipherable; many doppelganger narratives lead to the replacement of the initial protagonist by the double which has progressively intruded into their life, and something like this appears to happen in Performance – as Harry’s gang catches up with Chas, he seems to decisively reject what he has been shown of his own true self by shooting Turner in the head. But as the camera follows the bullet into Turner’s brain it smashes through an image of Jorge Luis Borges (who has been previously referenced a couple of times with shots of one of his books) before we get a glimpse of Chas being driven away in Harry’s Rolls and see that it’s actually Turner in the back seat. Have the two men melded into a single entity? Or is it actually the bored artist who has triumphed in the competition between destructive violence and creativity? Either way, it seems that the victor is doomed, being driven away to his death.

While the film is full of references to art and literature (more than I’m capable of deciphering), the prominence of Borges is highly suggestive, with his self-reflexive labyrinths in which characters become lost and transformed within hermetic, solipsistic literary constructions. Performance moves from exterior reality (the brutal gangster milieu) to interior subjectivity (Turner’s mansion which seems removed from time) and re-emerges into reality for a brief coda which remains enigmatic and irresolvable. This uncertainty is a fitting summation of the transformative events of the ’60s which, despite the promise of fundamental change, eventually led back only to a deeply reactionary conservatism. (Another layer altogether is suggested in an essay by Nadia Choucha which traces the roots of Cammell’s script back to the occult elements of the 19th Century Celtic Revival and the Order of the Golden Dawn, in which Cammell’s father was deeply involved; Cammell’s childhood was steeped in esoteric influences from W.B. Yeats and S.L. MacGregor Mathers to Aleister Crowley, and he would have been well aware of the idea of the Changeling, which seems pertinent to the film: “Scottish Fairylore, Occult Duality and Donald Cammell’s Performance” in Strange Attractor: Journal Five, eds. Mark Pilkington & Jamie Sutcliffe, 2022.)

*

Performance was made at a time when established channels for production were loosening; studios were in a more precarious position after the impact of television in the ’50s and the enforced changes to long-established business practices after the U.S. courts ruled that the majors must divest from ownership of their own theatres. Competition increased just as censorship began to weaken and audiences skewed decisively towards a younger demographic. These changes in the U.S. had ancillary effects in Britain where production had been dependent for a long time on American money. While the counterculture pushed social change in the U.S. alongside resistance to the Vietnam War, developments in fashion, music and film in the U.K. gave Britain an exotic appeal which attracted renewed interest from Hollywood as filmmakers like Richard Lester, John Schlesinger and Michael Sarne brought the Swinging Sixties to the screen.

It was in this atmosphere that usually cautious companies took chances. Probably at no other time would a company like Warner Brothers back a project like Performance, with two people who had never directed before co-directing an esoteric script full of sex and violence. It was no doubt the casting of Mick Jagger which clinched the deal, but that also caused problems later. Having been left alone by the studio during the shoot, the first screening in Los Angeles of the cut Cammell, Roeg and producer Sandy Lieberson delivered was a disaster. Everybody hated it, not only because the narrative confused them, but also because Jagger didn’t show up on screen until almost halfway through.

Difficulties escalated as Roeg had to leave for Australia where he would shoot Walkabout (1971) and Cammell was left alone in a hostile environment to do further work on the film. He found an ally in editor Frank Mazzola, who was sympathetic to what Cammell was trying to do. In fact, the editing apparently became more radical because of the pressure to get to Jagger earlier. Dropping in shots of Turner spray-painting his studio in the mansion at least put him on screen close to the beginning, but the gangster story was also greatly tightened, becoming more fragmentary and impressionistic, with quick cuts and radical montages. Studio interference in this case served to push an already experimental feature further from established conventions.

Not surprisingly, Warners still hated the film when they saw the changes and release was delayed a further two years before they finally dumped it without fanfare after the world it depicted had already moved on, making it seem dated – though, removed from that period, it now seems remarkably fresh and timeless.

Ironically, Roeg also disliked what Cammell had done with the film and wanted his name taken off the credits. Ironic, because Cammell’s highly compressed, allusive style, which pointedly ignores linearity, became the style Roeg used for most of his own features, in fact used so consistently that it became indelibly associated with his work to such a degree that for a long time Performance was attributed to him, with Cammell being pushed back into the shadows. It didn’t help that Cammell had difficulty launching any other projects – he completed only three subsequent features (compared to Roeg’s more than fifteen theatrical and television films): Demon Seed (1977), which was a job for hire, White of the Eye (1987), and Wild Side (1995), from which he had his name removed after the producers took the film away from him.

The film’s stylistic innovations, which also included Jack Nitzsche’s experimental score and what is probably the first music video embedded in a mainstream movie with Jagger’s “Memo From Turner”, have been absorbed into the filmmaking lexicon in the ensuing decades, although seldom in service of Cammell’s dense, multi-layered infusion of art and literature into the narrative space. Warners might have thought they’d be getting a pop-infused entertainment akin to Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964) or Help! (1965), but they got something much darker and more interesting which leaves an indelible impression on the viewer, even if its meaning ultimately remains somewhat opaque.

(It seems strange that just a year after Warners dumped Performance, they financed another British feature by a transgressive filmmaker – Ken Russell’s The Devils [1971] – which they hated perhaps even more. We should be grateful that Performance is actually available in this new restoration, since the company continues to suppress Russell’s masterpiece.)

*

The Disk

Criterion’s new 4K restoration reflects the film’s origins, with a grain-heavy image and vibrant colours. The technical rough edges of Roeg’s cinematography, much of it hand-held, add to the narrative’s breathless sense of urgency. The disk restores the original UK mono soundtrack which was replaced on the Warner Archive Blu-ray with an alternate track prepared for the American release on which Johnny Shannon re-recorded his dialogue to minimize his Cockney accent; although not really damaging, making Harry Flowers sound a bit more upper class does mar the film’s verisimilitude.

The Supplements

Although there’s no commentary, the disk includes two-and-a-half hours of extras which illuminate the context out of which the production emerged. These begin with Kevin Macdonald and Chris Rodley’s documentary Donald Cammell: The Ultimate Performance (1:10:23, 1998), previously available on Arrow’s White of the Eye Blu-ray; this covers Cammell’s life as well as his film projects, from his early days as a precocious painter, his esoteric interests (both Aleister Crowley and Kenneth Anger figure prominently), and his idiosyncratic entry into the film business, which involved more struggle and frustrations than success, leading eventually to his suicide in 1996.

There’s also an assembly of additional interview clips with the main cast members from the documentary shoot which focus on their work with Cammell and the particular challenges they faced on the shoot (34:45).

Two archival featurettes deal with the making of the film (2007, 24:49) and, from the time of the original release, Mick Jagger’s acting debut with a focus on his one musical number, “Memo From Turner” (4:52).

There’s a new featurette on the re-dubbing of Shannon’s performance (4:38) and a video essay on David Litvinoff (20:03), a friend of Cammell and the Rolling Stones whose connections with the London underworld not only facilitated aspects of the production but also provided quite a few specific narrative details (which caused him some trouble when associates realized he’d been giving away their secrets).

A trailer (2:46) shows how Warners struggled to find a way to sell the film, and the booklet contains an essay by critic Ryan Gilbey and a reprint of a 1995 article by Peter Wollen which delves into Cammell’s artistic influences and the various romantic traditions which are embedded in the film’s design and structure.

Comments