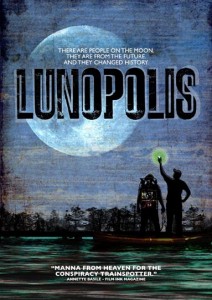

DVD of the week: Lunopolis

There are two main types of time travel story. The first treats time as little more than another spatial dimension, with the traveler heading off to see something in the past or future as if going to another country. H.G Wells’ The Time Machine was of this type, the title machine essentially just a device to move the narrator into a fictional world where Wells could examine the exaggerated effects of class conflict pushed to its logical extremes.

The second type of story directly confronts the logical paradoxes inherent in the concept of time travel. While James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984) is primarily a very effective action movie, he handles the time travel paradox skillfully, with John Connor sending Kyle Reese back in time to protect Connor’s mother and while he’s at it make her pregnant so that Connor can exist and, in the future, send Reese back in time to become his own father.

A couple of other recent films deal directly with paradox as the centre of their narratives. In Shane Carruth’s Primer (2004) some techies invent a machine which can project them into the future where they can access useful information and bring it back, but the process produces problematic side effects in the form of duplicating anyone who uses the machine. This is reminiscent of David Gerrold’s short novel The Man Who Folded Himself (1973), in which the protagonist ends up being endlessly duplicated as he moves through time until he literally becomes everyone in the universe.

Nacho Vigalondo’s Timecrimes (2007) is a brilliantly constructed puzzle which also deals with a kind of duplication as the protagonist is inadvertently sent back a few hours and sees his past self as an imposter. His behaviour becomes unhinged as he complicates things by repeatedly using the machine to go back briefly, producing more duplicates who end up in violent conflict with each other.

And now we have Matthew J. Avant’s Lunopolis (2009, and just released on DVD), which combines time travel paradox with elaborate conspiracy theories, all packaged in a fake documentary format which adds a sense of immediacy to the story, but also creates a few conceptual problems as well.

French academic Jean Francois Champollion VI, having discovered in 1992 a collection of videotaped footage shot by some university students, pieces together the story of what happened in the twelve days leading up to December 21, 2012 (yes, the very day supposedly predicted by the Mayan calendar as the end of the world as we know it). Champollion helpfully surrounds this found footage with the testimony of experts who fill in the gaps and explain the complex concepts involving time travel which underlie the grand conspiracy laid out by the film. You see, there are people on the moon and they control human affairs. They do this by travelling through time and altering past events to create a new and supposedly better future. They are led by J. Ari Hilliard, founder of the Church of Lunology and discoverer of the secret of immortality.

Like most found-footage movies, Lunopolis aims to create an air of reality and conviction around a fantastic story. What distinguishes Avant’s movie from most others of its kind is the inclusion of the extra contextual material to expand on and explain the found footage. Generally the audience is left to form their own opinions, but here we have something closer in form to a conventional documentary. This is both a strength and a weakness, however. Found-footage films are a game played with the audience, aimed at assisting us in suspending our disbelief. While the approach used by Avant allows him to lay out some fairly elaborate concepts which would be more difficult to explain if he had stuck strictly to the students’ found footage, we know that much of what the “experts” are talking about is not actually true (the Church of Lunology, for instance, is an obvious pastiche of Scientology, with J. Ari Hilliard standing in for L. Ron Hubbard), so the more overt documentary material actually undermines the found-footage narrative by emphasizing the fictional nature of the film – exactly the opposite of the effect the found footage technique aims to create.

After a brief, somewhat cryptic television news report about a viral Internet video which may or may not show some kind of supernatural event at a shopping mall, we are introduced to Matt (director Matthew Avant) and Sonny (Hal Maynor). These two young filmmakers are embarking on a documentary investigation triggered by a panicked phone call to a late night conspiracy-themed show in which a terrified voice talks of people on the moon who are controlling world events. The follow-up arrival of some documents, including a strange Polaroid photo with GPS coordinates written on the back, leads them to a partially submerged cabin in a Louisiana swamp beneath which they discover a vast, seemingly deserted installation. Deep inside they find an odd machine which they take back to the university.

Needless to say, the device turns out to be a prototype time machine and the fact that they’ve stolen it leads to them being watched and pursued by mysterious figures.

All of this is presented in typical, rough-edged “found footage” style. Director Avant gets around some of the limitations of the format by having his team shoot with two cameras, which permits more conventional editing of some scenes (being sure to include occasional shots where the cameras glimpse each other). But these scenes are intermittently interrupted by more formally shot interview clips featuring the heavily-accented Frenchman Champollion who comments on and occasionally offers an explanation for what we are seeing, and later by various former members of the Church of Lunology and scientists. So, unlike movies like The Blair Witch Project (1999), The Last Exorcism (2010), or Paranormal Activity (2009), in Lunopolis we don’t simply have a collection of found footage; here, that “raw material” is being framed and shaped by someone other than the characters we see in the main body of the narrative.

This seems to become problematic towards the midpoint as we suddenly get a long, traditionally structured talking-heads sequence in which a variety of experts suddenly appear to explain the background to what the young filmmakers are discovering and to lay out an elaborate theory of parallel worlds and how the discovery of time travel has led to a vast conspiracy which controls world events.

This story involves J. Ari Hilliard, who was born in the ’40s (and mysteriously published the foundational text for the Church of Lunology seven years before his birth), discovered how to move through time and, on December 21, 2012, went back with others to 350 BC where he set about altering events to “correct” what he saw as historical mistakes. Eventually, Hilliard and his people established a civilization on the moon from which to control history. This involved a lot of time travel, which resulted in an increasing number of problems, because any action always has unforeseen consequences. And, as in many other time travel stories, each action results in a duplication, creating more and more parallel worlds, each a little different than the others, but all close together and occasionally impinging on each other (resulting in such phenomena as ghosts, deja vu, clairvoyance).

By this point a big question hangs over the film: if these theories and this history are so obviously widely known and studied by experts, how can they be such a mystery to the filmmakers, and why are mysterious forces connected with the Church of Lunology threatening them because of what they are discovering? Although this problem is at least partially solved at the end of the film when the source of the found footage is revealed, on first viewing it tends to undermine the credibility of the narrative and this mid-section seems like an awkward way to insert a massive dose of exposition which Avant couldn’t work into the narrative itself.

But despite this problem, the big story, the conspiracy involving time travel and immortality, multiple parallel worlds and alternate histories, is an entertaining construct, and Avant keeps it moving at a swift pace so we stay interested even though we may not always be fully engaged. Eventually the film circles back to that opening news report, but now we understand exactly what happened. The resolution ties together many of the film’s convoluted threads (with a not entirely surprising revelation about the identity of a major character), and is dramatically satisfying.

On the level of filmmaking, Lunopolis is impressive for a low-budget first feature. The elegantly formal interview clips make it clear that the jerky found footage sections are a deliberate creative choice, and the contrast between the two modes adds a sense of urgency to the rough footage. Most of the performances seem natural and convincing, with Dave Potter a stand-out as the reclusive David James, who shows up to give the filmmakers some crucial information, though his motives turn out to be more sinister than his easygoing manner suggests.

The DVD also includes a commentary track with writer-director-star Matthew Avant and his brother Nathan (who plays Nate, one of the cameramen), moderated by associate producer Michael David Weis. It’s a chatty track which offers some interesting information on the genesis of the film and the ways Avant managed to squeeze production value out of a limited budget, though at times the three seem to forget that they have an audience and waste time joking amongst themselves.

Overall, Lunopolis is an intriguing concept, executed with skill and enthusiasm, though not always completely successful in achieving its aims.

Comments