Recent viewing, part 2

You could make an interesting double bill out of Daniel Barber’s Harry Brown (2009) and Joe Cornish’s Attack the Block (2011). Both are set in crime-ridden British housing estates where residents are terrorized by youth gangs, both have a gritty tone which strives to create a sense of relevance and immediacy. But while they have a similar starting point, they go in very different directions.

Harry Brown stars Michael Caine as a former military man, now a lonely, widowed pensioner who sees little purpose in life as he watches the neighbourhood kids dealing drugs, vandalizing cars, and beating various people up. When his only friend, Leonard (David Bradley), is murdered and the police seem unable to do anything about it, Harry goes all Death Wish, gets a gun from a couple of drug-dealing scumbags (the movie’s best sequence, with Sean Harris a truly disturbing villain) and tracks down the kids he believes killed Leonard, killing them one by one. These kids are basically nasty little sociopaths, but the film eventually reveals them to be merely the latest generation in a long line of criminals, raised in the family ways and protected by their elders. Like most modern vigilante movies (Neil Jordan’s The Brave One [2007], James Wan’s Death Sentence [2007]), Harry Brown doesn’t allow itself the conscienceless pleasures of the original Death Wish (1974), maintaining a kind of bleak, moralizing hopelessness.

In Attack the Block, an all-out genre pleasure, the kids aren’t hereditarily corrupt and they don’t have any kind of familial support. They’re aimless, faced with no prospects, no guidance, and committing petty crimes in a thoughtless way. We first meet them as they mug a young nurse (Jodie Whitaker) walking home one evening. She manages to get away from them only because something falls from the sky and destroys a car parked nearby. Turns out some kind of alien creature has just landed in South London and the boys chase it and beat it to death with sticks. They take it to a dealer they know (Nick Frost) who they think will be able to identify it because he spends all his time watching nature shows on the telly. And then more objects fall from the sky and the kids go out to hunt aliens – only these ones are different, very nasty, and harder to kill. With the police after them for the mugging, and no one believing what they’ve seen, the kids become the only line of defence against the invasion. They eventually team up with the nurse (apologizing because they didn’t know she lived in their building) and Moses, the 16-year-old leader (the impressive John Boyega), single-handedly destroys the creatures. In defending their turf – and realizing that their victims actually have identities and feelings – the kids develop the one thing they’ve been lacking, a sense of community and belonging. Funny, suspenseful, with exciting action scenes, Attack the Block is raised above the level of B-movie by its well-drawn characters and by the quality of the acting; while the kids begin as generic little thugs, we gradually come to see them as what they really are – children who’ve grown up in a completely shattered community.

While Harry Brown maintains its view of the kids as sociopathic monsters, Attack the Block ends up humanizing them and suggesting that they actually have the potential to be decent citizens – they just need to find some sense of purpose (some English critics even complained about the way the movie eventually makes them sympathetic, apparently preferring the Harry Brown view of disenfranchised youth).

*

A somewhat more sophisticated treatment of criminality, responsibility, and the possibility of genuine evil can be found in Tom Hooper’s Longford (2007). This fact-based HBO film deals with the relationship which developed over a number of years between Lord Longford (Jim Broadbent), a quiet, gentle, charitable man, and Myra Hindley (Samantha Morton), England’s most notorious female serial killer who, with her lover Ian Brady, murdered five children in the mid-’60s and buried them on Saddleworth Moor outside Manchester. Sentenced to life, Hindley wrote to Longford who had a decades-long commitment to visiting prisoners, fighting for reform, and arguing that anyone, no matter what their acts, was capable of redemption. Longford finds Hindley charming and intelligent, and at the risk of his career, not to mention severe strain on his marriage to the author Elizabeth Longford (Lindsay Duncan), he begins a campaign to gain her parole.

There’s a child-like charm in Longford, his belief in the essential goodness of people rooted in his religious convictions, and he fights against public opinion and political expediency in an attempt to help Hindley, eventually joined in his fight by his wife who comes to believe that Hindley is receiving harsher treatment than many another murderer just because she’s a woman. When it becomes apparent that he has been manipulated for years, that the murderess has been using him, he becomes an object of public vilification, but to the end he maintains his belief that he gained something of value from the relationship. This is a film about the possibility of viewing events, even horrific ones, from a variety of angles, and of seeing people as more than just the sum of their worst actions – while at the same time indicating that someone’s deepest motives may never be clear to us. It’s aided immensely by what is possibly Broadbent’s finest performance, well supported by Morton and Duncan, with the versatile Andy Serkis turning in a chilling performance in his few scenes as Ian Brady.

*

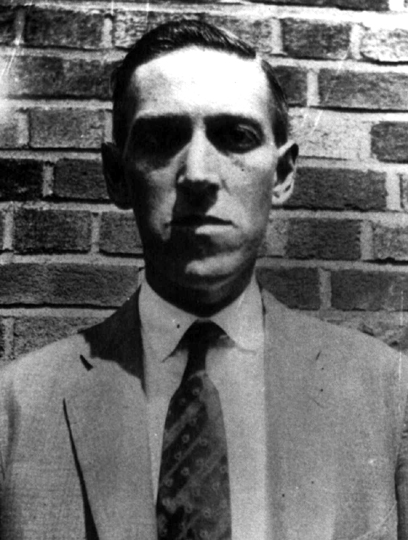

I was pleasantly surprised by Frank H. Woodward’s documentary Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown (2008). In the past couple of decades, H.P. Lovecraft has gradually become accepted as more than an over-heated, adjective-heavy pulp writer, but I’d rather expected this to be another fan-oriented piece, driven by amateur enthusiasm. (There’s a mini industry in amateur Lovecraft adaptations, many shorts available on a series of DVDs under the general title The Lovecraft Collection, as well as Andrew Leman’s two features The Call of Cthulhu [2005] and The Testimony of Randolph Carter [1988].) Instead, it’s a solid, well-researched account of HPL’s life and work, packed with interviews with writers, filmmakers and academics who are without exception articulate and insightful. Woodward doesn’t shy away from Lovecraft’s difficult characteristics, particularly his xenophobia and racism, and yet manages to build a convincing argument for his value as a writer. Personally, I’ve always had a conflicted response to Lovecraft’s work – drawn to the scope of his mythology with its chilly view of human insignificance in a universe which has little interest in our existence, while finding his prose a generally hard slog to get through. I guess what appeals to me about him is the odd incongruity between his imagination and his oddly constrained life in New England. How did the former emerge from the latter? Although that question is not fully resolved by this documentary, the comments of Neil Gaiman, Guillermo Del Toro, Peter Straub, Ramsay Campbell, S.T Joshi and others go a long way towards making me want to go back and re-read some of the stories.

*

Gainsborough Pictures was founded by Michael Balcon (later the head of Ealing Studios) in 1924, making a variety of supporting features, with Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938) as the pinnacle of its output. In the late ’30s, Rank became involved with the studio and, during the war, it turned out a series of melodramas and women’s pictures (often referred to as bodice-rippers and frequently starring Margaret Lockwood). In 1950, the final year before Rank closed the studio, Terence Fisher (soon to be the mainstay of Hammer’s horror production) co-directed with Antony Darnborough an elegant damsel-in-distress film starring Jean Simmons and Dirk Bogarde. A precursor of stories like Polanski’s Frantic (1988) and Jaume Collet-Serra’s Unknown (2011), So Long At the Fair has Simmons arriving in Paris with her brother (David Tomlinson) just before the opening of the World’s Fair in 1889. They spend an evening on the town, return to their hotel, and in the morning Simmons finds herself alone – but not only has her brother vanished, the staff of the hotel deny that he was ever there and his room no longer exists. Elegant production values and an excellent cast maintain a fine sense of growing desperation as Simmons struggles to find anyone who’ll believe her preposterous story. Luckily, she encounters a young English painter (Dirk Bogarde) who actually met her brother that evening and together they set out to solve the mystery. As with most stories of this kind, the resolution is less satisfying than the build-up, but the film has a lot of charm and a greater lightness of touch than the Gothic horrors Fisher eventually made for Hammer.

*

Chains (1949) is the first film in the Criterion Eclipse set devoted to director Raffaello Matarazzo, a name previously unfamiliar to me. Made at the height of post-war neo-realism, this appropriates some of the grittiness from that movement, but blends it with a kind of rampant, over-heated melodrama which threatens at almost every moment to slip into self-parody. A fast-paced tale of a woman’s suffering, Chains is nothing if not entertaining, manipulating audience emotions shamelessly even as it courts ridicule. Yvonne Sanson is Rosa, a woman seemingly happily married to mechanic Guglielmo (Amedeo Nazzari) and mother of two children, an adorable little girl (Rosalia Randazzo) and an observant older boy (Gianfranco Magalotti). One evening a car thief with engine trouble arrives at the garage and he turns out to be Rosa’s old fiance, Emilio (Aldo Nicodemi), who disappeared into prison years ago. He immediately decides that he wants her back and becomes one of the most oppressive stalkers you can imagine. Rosa’s inability to drive him away becomes a source of deep viewer discomfort – one of the film’s biggest structural weaknesses is delaying until much too late a flashback to the happy days they once shared: we’ve come to see Emilio as a threatening creep by then and it’s hard to credit any genuine romance between the two. Unfortunately, the son observes what’s going on and in the film’s best scene (here there are echoes of De Sica’s devastating The Children Are Watching Us [1944]) he desperately tries to prevent his mother going to meet Emilio. Although she’s actually planning to have it out with the guy for the last time, wanting her family rather than him, Guglielmo turns up and someone gets shot. Matarazzo piles on the humiliation in ever larger doses, so heavily that the convolutions leading to a happy resolution and reconciliation are utterly implausible, although all that Catholic guilt and redemption apparently appealed to Italian audiences, making Chains one of the big hits of the year.

Comments