Lionel Rogosin: On the Bowery (1956)

The announcement that Milestone will be releasing Lionel Rogosin’s On the Bowery next February reminded me that I still hadn’t got around to watching the three-disk set of Rogosin’s work that I bought in Paris in the summer of 2010. I’d never heard of Rogosin at the time, but the packaging immediately caught my attention while I was browsing the DVD shelves at the Virgin store on the Blvd. Poissonniere. The set, subtitled “Les Origins du Cinema Independent Americain”, contains three films made between 1956 and 1965, plus a wealth of supplementary material.

Watching On the Bowery (1956) reminded me that, even with everything that’s been made available in the past couple of decades, it’s still possible to be surprised, to be struck by a sense of revelation.

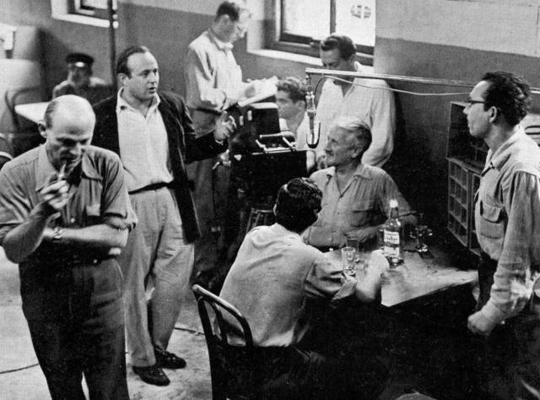

Lionel Rogosin grew up privileged, his father successful in the textile industry. Lionel got a degree in chemical engineering in order to join the family business, but after the war he travelled widely in Europe and Africa and in the early ’50s decided to make a film about apartheid in South Africa. But first, he needed to learn how to make a movie, and he set out to practice by making a short film on skid row in New York. Spending six months hanging out in bars and flop houses, he got to know the people living on the Bowery and even found his collaborators there, meeting writer Mark Sufrin and cameraman Richard Bagley in bars and recruiting them for the project.

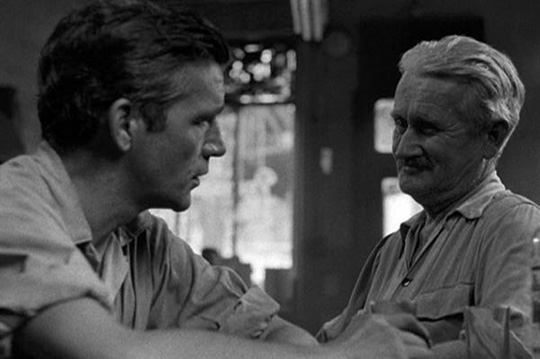

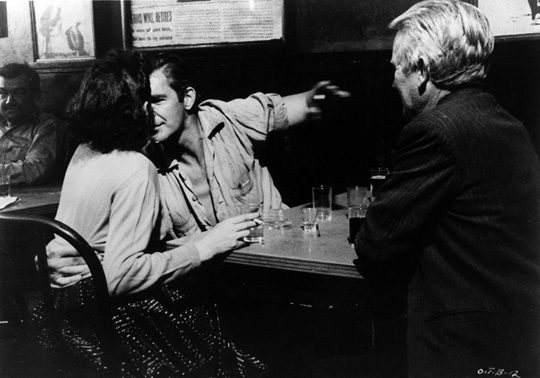

Having befriended several of the alcoholics on the street, eventually casting them as his leads, Rogosin initially tried to shoot without any script, but quickly discovered that that approach wouldn’t work. He, Sufrin and Bagley spent about five hours brainstorming some ideas and came up with a slender narrative about a railway worker (Ray Salyer) who arrives on the Bowery with very little money, falls in with a local named Doc (Gorman Hendricks), struggles to find work, and gets caught up in a cycle of drinking and sporadic determination to sober up. Finally, after Doc rolls him for all his meagre possessions, the older man gives him some of the stolen money so that Ray can get out of the Bowery and go looking for work in Chicago.

What can’t be conveyed by a brief summary of that very slight story is the amazing sense of detail and texture which Rogosin’s documentary eye brings to the film. The sights – and, it seems, the smells – of the Bowery are so richly conveyed that the weight of these broken lives becomes almost unbearable at times, Bagley’s camera lingering on a remarkable collection of faces which have the aura of Rembrandt portraits and the nightmarish quality of a Bosch vision of hell.

If we’ve seen images like this before – argumentative alcoholics crowded into seedy bars, drunks stumbling down garbage-strewn streets, lying in gutters and doorways, being woken by cops on park benches and hauled away, lining up at soup kitchens and crashing in doss houses – we’re used to seeing them crude and grainy, as if the texture of the image were dictated by the content. But Rogosin and Bagley shoot them in pristine, luminous black-and-white with the sharp clarity of a fine nitrate print. The formal beauty of the photography honours the lost people we see on screen; rather than distancing them from us, the images force us to recognize the humanity we share with them. Rogosin is showing us this world not with the condescending detachment of an outsider, but from the inside.

There’s a powerful ethnographic quality to On the Bowery, the sense of seeing an unfamiliar culture put under a microscope; given the time at which the film was made, this approach inevitably carried political implications. When the film won first prize for documentary at the 1956 Venice Film Festival, U.S. Ambassador Clare Booth Luce snubbed Rogosin at the reception because she was appalled that he would present such a view of the States at a time when the country was in competition with the Soviet Union for the allegiance of other nations. It’s not surprising that Rogosin was more honoured in Europe than in his own country; his adaptation of neo-realism to a home-grown subject was a finger in the eye of Hollywood, the industry whose chief purpose was to present a mythic self-image of America to the world.

The Carlotta set, which also includes Come Back, Africa (1959) and Good Times, Wonderful Times (1965), presents a beautifully restored print of On the Bowery and also includes some illuminating supplements. In addition to some DVD-ROM text files of reviews, articles and a dialogue transcript, there is an excellent 47-minute documentary by Rogosin’s son Michael about the making of the film which includes sections of interviews Rogosin gave in the last years before his death in 2000, plus a couple of shorter pieces – an introduction in French by the director of the Cineteca di Bologna, which restored all the films in the set, and a brief look at the Bowery today, gentrified like so many of New York’s formerly run-down neighbourhoods.

Comments