Disk of the Week: My Son John (1952) – Bad craziness in Hollywood

In the past couple of years Olive Films has released an eclectic variety of movies on DVD and Blu-ray, from noir to comedies, exploitation to obscure indie dramas – recent releases include Bresson’s The Devil, Probably alongside Aldrich’s Twilight’s Last Gleaming! But for me, one of their most interesting releases is a fine Blu-ray edition of Leo McCarey’s My Son John (1952). This tonally discordant drama was made at the height of Hollywood’s “red scare” period, when the industry came under attack by the House Un-American Activities Committee and some Hollywood figures were falling over themselves to cooperate with Joe McCarthy and his congressional cohorts, while others made principled stands and found themselves on the infamous blacklist, barred from working in American movies (at least under their real names), or forced to leave for England and Europe.

Mainstream Hollywood tended to avoid actually talking about the ideas of communism, presenting it instead as a vague un-American nemesis in numerous thrillers about intrepid agents foiling the dangerous plans of foreigners. The fact that no one was willing to discuss the political ideas of this conflict had some interesting side effects. Sam Fuller made Pickup on South Street (1953), a gritty noir-inflected story about a petty pickpocket who inadvertently gets hold of some microfilm intended for Soviet agents. But as cynical as the film is about patriotism, the almost total lack of political discourse made it possible for the French to easily transform the microfilm into drugs in their dubbed version, clearly indicating that the microfilm (and the communist threat) was nothing more than a MacGuffin on which to hang one of the director’s finest examinations of moral squalor.

The fringes of the industry produced a few bizarre fantasies about the communist threat, like Harry Horner’s Red Planet Mars (1952) in which apparent radio messages from Mars inspire a resurgence of belief in God and the overthrow of the Russian empire; and William Asher’s The 27th Day (1957) in which an alien device is ultimately used to kill “every enemy of freedom” (i.e. communist) on the planet … implying, of course, that there was something fundamentally different about commies, as if they were an entirely different species.

My Son John (1952)

Leo McCarey’s My Son John, made the same year as Red Planet Mars, also sets God and unquestioning faith against the communist threat. But what makes McCarey’s mainstream movie so interesting is that it presents the essence of the era’s paranoia in a completely undisguised form. The film was quickly considered an embarrassment and failed at the box office – but not because of poor filmmaking; after all McCarey was a highly respected Oscar winner, co-writer John Lee Mahin had been nominated twice and had just in the previous two years written Panic In the Streets, Quo Vadis and Show Boat, while the other writer Myles Connolly had also been nominated for an Oscar in the ’40s. But perhaps it was this very pedigree which caused the sense of embarrassment: McCarey and his team gave credence to a mindset which was better left vague.

McCarey had had a remarkable career in the previous three decades, following dozens of silent shorts in the ’20s with a number of landmark movies in the ’30s, including Duck Soup (1933), the greatest of the Marx Brothers’ anarchic comedies; the heartbreaking Make Way For Tomorrow (1937), no doubt a strong influence on Ozu Yasujiro’s masterpiece Tokyo Story (1953); and The Awful Truth (1937), one of the greatest screwball comedies about marriage. In 1944, he had one of his biggest successes with the Oscar-winning Going My Way. This mixture of religiosity and sentimentality, quickly followed by a sequel the next year, The Bells of St. Mary’s, indicated a growing conservatism that would culminate in My Son John, a movie which awkwardly combines the many strands of his career – domestic melodrama, comedy (with slapstick moments), and a deep sentimentality about religion.

In My Son John, we meet a small-town family, the Jeffersons, just as the two football-star younger sons are leaving for the Korean war. But something is a little off, because the older brother John has not come home from his job in Washington for the farewell dinner. When he finally appears a week later, we immediately sense something alien about him. While his brothers are stocky athletes proud to go off and fight, John (Robert Walker) is an intellectual, highly verbal and mannered in a way which says with neon-brightness that he’s no longer a smalltown boy, but rather a sophisticated city man immersed in some federal bureaucracy (his questionable politics are also conflated with mannerisms which hint unsubtly at homosexuality).

There are immediate signs of friction between John and his father, Dan Jefferson, played by Dean Jagger as an earnest, forthright, simple man with a stolid sense of patriotism. Walker, in all their scenes together, constantly has the suggestion of a derisive smirk on his lips, and obviously takes pleasure in pushing dad’s buttons with off-hand comments. Standing between them is Lucille, wife and mother, one of the most jittery, neurotic characters ever presented by Hollywood as an emblem of noble motherhood. In an early scene the family doctor, a friend, shows up and forces tranquillizers on her even though she doesn’t seem incapacitated by her sons going off to war; just trust me, he says, they’ll make you feel better, as if simply being a woman were a form of illness. Although she secretly doesn’t take the pills, the right of the doctor and her husband to make such a decision for her is not questioned.

This role was Helen Hayes’ return to the big screen after seventeen years away and she pours an impressive amount of energy into the part. But it’s uncomfortable to watch, because this mother is seen purely as a binding agent to hold the men of the family together. As the force for social stability, she’s obviously problematic because there’s no firm core to the character. She lives only to serve men’s needs and when the two main men in her life are at odds, she’s utterly torn. She loves her husband and insists that he deserves respect, but when John explains his political views to her – a canny, benign blending of communism and Christianity (obviously intended to show just how underhanded these commies are) – she’s immediately reassured and thinks that Dan would reconcile with John if it could all just be explained to him. But Dan wants no explanations.

As a representative of good, solid American manhood, Jagger’s Dan now looks like the dangerous figure in this triangle. He’s distrustful of education and intellect, he believes that the strength of his country depends on everyone thinking, believing and saying the same things. When John insists on reading the speech Dan has written for an upcoming American Legion meeting, a long string of platitudes, he asks his father whether these are his own thoughts or borrowed from other sources. Dan admits that every phrase is borrowed, a reiteration of “received wisdom”, and seems proud that he’s managed to avoid any original thought. At one point, demanding that John explain his beliefs, Dan actually smacks him across the head with a Bible, a symbolically telling moment given that the foundations of this America (in McCarey’s view) rest firmly on the Catholic Church – an interesting idea in itself given that much of America distrusted the Church almost as much as it did communists, given that it was a vast organization ruled by foreigners who answered to a higher authority than U.S. interests (it was only a few years later that John Kennedy had to publicly assure the electorate that he would not in fact defer to the Pope if he was elected president).

It’s interesting to see how the authoritarian, patriarchal views of McCarey’s movie clearly echo much of what we heard during the recent interminable U.S. election. The urge to trust in the received wisdom of conservative religious institutions; the distrust of women’s independence … in the aftermath of the election Bill O’Reilly even lamented the final death knell of the Cleaver family, Ward, June and the Beaver.

The demise of the Soviet Union helps to throw all this into clear relief: it was not so much communism itself that was the threat as it was the idea that independent thought threatened the status quo. It’s education, critical thinking, that undermines “America”. (Note that in Texas, the Republican Party has discounted the very idea of critical thinking, declaring that it has “the purpose of challenging the student’s fixed beliefs and undermining parental authority”.) What My Son John urges is the very “faith-based” society that the American Right has been clamouring for in recent years, a society which discounts scientific evidence no matter how dangerous the consequences because there’s so much comfort in received wisdom and the assurance that a fading establishment (largely white male) can perhaps continue to hold onto power. (And, of course, this rhetoric is wrapped in completely meaningless warnings about President Obama’s subversive “socialist/communist” aims, not to mention his un-American otherness.) In McCarey’s movie the Church stands as a symbolic representation of this patriarchal faith, no matter what its actual denomination.

Seen now, as condescending as Walker’s John sometimes appears, it’s the parents who come across as the scary characters. And their apparent triumph at the end – after faceless communist agents have killed John because his “faith” in the cause has faltered – signals a closing down of rational thought. The final moments of the film present John’s recorded commencement address at his old school, a tape played beneath a beam of celestial light to a room full of sombre students. And what does John, having finally seen the error of his ways, have to tell them? Only that higher education is the path to hell and that an active intellect leads to an egotism which is easily exploitable by unscrupulous enemies who are ready to use your highest aspirations for their own insidious ends. In other words, as people like Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck and their ilk are constantly reiterating, ignorance is strength and the more ignorant the population is, the stronger the nation will be.

*

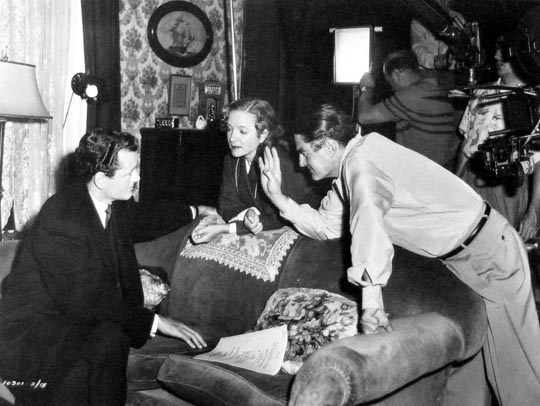

About that ending: this strange movie becomes almost surreal in the final stretch because Robert Walker died before production was completed and McCarey was forced to cobble bits and pieces together to finish the story. There are odd, disjointed images, full of portent but unclear in meaning, noir-ish shots of John pacing anxiously in dark rooms, phone conversations in which we see him speak but can’t hear his voice … and his death in a taxi on a Washington street, with closeups taken from Hitchcock’s Strangers On a Train superimposed into the back seat. It’s an interesting study in the limits of editing to get around a problem of great magnitude and, while it fails in terms of narrative coherence, it adds a strange note of inadvertent black comedy to this oddest of red scare movies.

Comments