Year End 2012

A few days ago I spent the evening with four friends at our annual get-together to discuss what we had seen during the past year. Back when I was first invited to join the group years ago, there would often be heated arguments about the particular merits of this or that movie, but we’ve all mellowed since then and even when there are disagreements, we no longer bother to get into lengthy discussions, just acknowledge that our opinions differ and move on. It’s become a much more relaxing event, with a pleasant meal provided by our hosts and long discursive conversations which drift away to other subjects as often as they focus on film.

I mention this because I find that this year I don’t have much interest in compiling an annual “best of” list – something which used to seem de rigueur to me. Looking back over the year’s viewing, I note that I tend not to go to many “serious” movies in the theatre any more … due in part to the fact that I dislike the ambiance of characterless multiplexes. I tend to save those films for home viewing. But of course that often diminishes the experience of watching them, not doing them the justice they deserve. Catch-22. In this sense, I realize that in some ways I’m no longer “qualified” to pass any kind of serious judgement on many of the movies I watch.

So … a few random comments on the past year:

Some of the year’s biggest movies in terms of budget, publicity and box-office receipts were so wretchedly bad that it’s hard to discount the idea that the mainstream industry is, creatively speaking, irreparably bankrupt. Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Rises, Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, Sam Mendes’ Skyfall and Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained are all misconceived from the ground up and executed with awesome degrees of self-importance, attempting to bludgeon their audiences into submission, hoping that the numbed viewer will stagger away thinking that they’d just had some kind of profound experience. What these filmmakers, at least the first three, seem to have lost is the ability to entertain, to recognize that even when attempting to deal with heavy themes (and really, are Batman, Alien and James Bond appropriate vehicles for “serious” discourse?), movies should offer the viewer some kind of pleasure.

The only really big movie I enjoyed in a theatre last year was one which bombed commercially and was thoroughly shredded by critics and fanboys alike: Andrew Stanton’s epic fantasy John Carter, a movie which successfully achieves exactly what it sets out to do … provide a rousing visualization of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ pulp fantasy novel about an embittered Civil War veteran who finds himself transported to the Red Planet where he’s drawn unwillingly into a devastating war and more willingly into a romance with the feisty local princess. Stanton brings a breathless adolescent love of adventure to the project which perfectly captures the appeal of the source, in effect imbuing a very large-budget project with a kind of child-like innocence, completely devoid of irony and pop-culture snark. No wonder it bombed.

For the most part, I enjoyed smaller, well-crafted movies that emphasized narrative and character over spectacle. Roman Polanski’s savagely funny Carnage, Tomas Anderson’s old-fashioned thriller Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The RZA’s Man With the Iron Fists. The year also saw the best “found-footage” movie yet, Josh Trank’s Chronicle. And, perhaps the highlight of 2012, a big-screen showing of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd, an impressive reminder of what power movies used to have before they were mostly conceived as consumer distractions. Only slightly less powerful were screenings of Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (from a new 35mm print, no less … that’s not likely to happen again!) and a double feature of Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein.

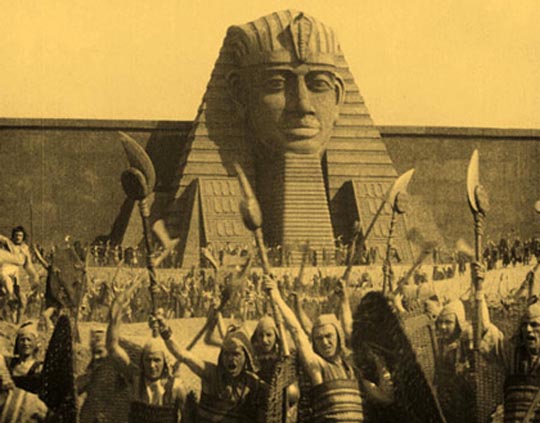

On video last year, we had the significant restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1921 The Loves of Pharaoh, a completely unexpected historical epic with vast sets and sweeping desert vistas (shot just outside Berlin!) about an arrogant ruler (Emil Jannings) who sets off a war which destroys his kingdom when he rejects the daughter of a neighbouring king in favour of a slave girl. Although this huge production was the film that landed the 30-year-old Lubitsch an invitation to Hollywood, once in the States he began to make the subtle comedies for which he’s now best known. The excellent Blu-ray edition from Alpha-Omega in Germany also includes a documentary about the film and its complex restoration.

I was impressed by a number of Criterion’s Eclipse box sets last year, particularly the Gainsborough Melodramas, Jean-Pierre Gorin’s essay films, the trilogy of Imperial adventures starring Sabu, and the wild, jazz-inflected Japanese New Wave movies of Koreyoshi Kurahara.

Criterion also released the first two features of Claude Chabrol, Le Beau Serge and Les Cousins, representing the remarkably assured beginnings of the director’s long career devoted to dissecting the pathological underside of bourgeois French society.

Matching Criterion as always over in region 2, the BFI continued its own valuable contributions to film history, with its ongoing releases of British documentaries (particularly the first two volumes of The Complete Humphrey Jennings), re-releases on Blu-ray of crucial works like Bill Douglas’ autobiographical Trilogy and his idiosyncratic historical epic Comrades, Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo’s unique Winstanley, Pasolini’s Medea, Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution … and the Flipside releases of Ian Merrick’s chilling Black Panther and Andy Milligan’s revelatory Nightbirds.

Perhaps the high point of the year was the BFI’s compromised release of Ken Russell’s masterpiece The Devils. They did a superb job considering the bizarre intransigence of Warner Brothers over this controversial film (including the company’s refusal to give them access to original film elements – the standard definition disk was taken from a Beta master provided by the studio – and the refusal to release the full director’s cut, or even to include the deleted scenes as a supplement). While both quality and completeness were undermined by this infuriating display of corporate derangement, the people at the BFI managed to come up with the best available version of the film and a collection of supplements which provide a rich contextual setting for the feature itself. Until somebody at Warners comes to their senses and unshackles this vitally important British film, this is as much satisfaction as we’re ever likely to get.

Finally, probably the most fun I’ve had all year has been working my way through the Three Stooges’ 20-disk Ultimate Collection, some 65-hours of beautifully restored comic anarchy on which Sony-Columbia dropped the price radically, making it an irresistible purchase. So far I’ve watched 87 of the 190 shorts (about 25 hours worth), working my way through them chronologically. I know that by 1945 the trio’s best work was already behind them and I’m rather dreading getting to the next volume because there are only a few more shorts before Curly bows out after suffering a stroke in 1947 … while the team was remarkably well-balanced between the aggressively bossy Moe, the frequently clueless Larry and the childlike Curly, it was Curly who somehow raised them to their full comic heights. Like many large men, he had a strange physical grace and the Stooges were defined as much by his peculiar vocal mannerisms as by their eye-poking, head-banging slapstick. While the Stooges’ brand of anarchy might lack the sophistication of the Marx Brothers, their sense of comic timing and the sheer gleeful destructiveness of their efforts just to get along in the world mark them as one of the finest examples of comedy as a subversive art.

Comments