Over-consumption and Diminishing Returns Part 2

Continuing my dialogue with friend Gordon Wilding about the ways in which our relationship to the movies we watch has changed in recent years …

I can look back at the years it took me to “possess” the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, starting in 1975 and ending in the late ’80s – not to mention spanning three continents. Each new encounter was filled with a sense of excitement and anticipation, the feeling that I was adding to an on-going understanding of a great artist’s work; and I would go repeatedly in an attempt to grasp what the films were doing to me (knowing it was his final film, I saw The Sacrifice three times in one week at Winnipeg’s late, lamented Cinema 3). His work holds a crucial place in my experience of the medium, and though I have all his films in my collection and have watched them all several times each since they first appeared on VHS and DVD, I nonetheless feel reluctant to re-watch them at home. It’s as if I’m afraid watching them yet again on TV, even a large HD screen, risks erasing those (already compromised) first experiences I had with them. (And yet I don’t think I’d have any problem if by some miracle someone screened them every year in a theatre; I’d happily go again and again.)

I came to Tarkovsky’s work through seeing Solaris in 1975 in London, attracted by its source in the Stanislaw Lem science fiction novel which I’d read in 1970; I can still recall the impact of its rich, slow rhythms and obscure conversations which pointed to an alternative to the western idea of character-through-action. (Although I eventually discovered that Solaris was far from Tarkovsky’s best work, I still found it hypnotically immersive when I watched the Criterion Blu-ray two years ago.) My next encounters were with two of his masterpieces, both seen in Hong Kong’s Cinema One film club in late ’80 and early ’81 – his overwhelming historical epic Andrei Rublev and his second SF film, Stalker (which I consider his greatest work); then came my favourite Tarkovsky film, the haunting Mirror, which I saw several times in London in 1984, around the same time I first saw Nostalghia (each film helping to illuminate the other); and finally The Sacrifice two years later, here in Winnipeg.

Ivan’s Childhood is the only one of his seven features that I’ve never seen on a big screen (in fact, my first encounter was with a rental VHS tape, which makes me shudder now!) and perhaps that’s why, despite its beauty and the richness of its moods, it has had less of an impact on me than the others … that and the fact that it more recognizably belongs to an established genre, the Soviet Great Patriotic War story, and thus seems a little less personal. (Perhaps that’s also why Solaris now seems like one of his lesser films, because it’s constrained by too many genre requirements; Stalker on the other hand, although like Solaris based on a science fiction novel, strips away most of the trappings to become a more internal experience, a philosophical argument between political materialism and an ineffable sense of transcendent spirituality.)

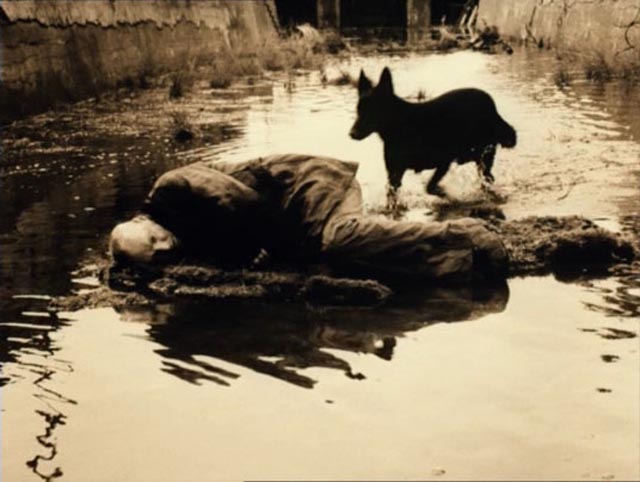

Thinking of the impact these films had on me in the theatre, I wonder what it would have been like to encounter the amazing work of Bela Tarr on the big screen. Damnation, Werckmeister Harmonies and the epic Satantango seem so overwhelming even on DVD that I can only imagine how much more they would have affected me in a theatre … the catch is, I never would have experienced these films at all without home video.

True, I do still encounter films which, like those of Tarr, have a deep impact even on DVD. For some reason, a number of Japanese movies spring to mind – Kobayashi’s monumental humanistic epic The Human Condition, which I first saw about a decade ago; several of Naruse’s subtle dissections of social despair; Yamanaka’s exquisite Humanity and Paper Balloons and Kinoshita’s deeply moving Twenty-Four Eyes. But even these don’t seem to have embedded themselves as deeply into me as films I saw three and four decades ago, because, I think, once again they required less effort to “acquire”.

GORD: Every movie we watch now is built on an initial early experience/memory. The films are powerful and lasting in our brains. We want to repeat the experience but find the ease and convenience somehow taking away from it. I think there is a need for a concerted effort on the viewer’s part to isolate themselves, to understand the nature of the medium (not the transmogrified mass culture experience of the multiplex/internet/netflix), but the nature of film as a storytelling medium – to sit in front of the film and try (hopefully) to wipe away the film’s source (dvd/bluray/theatre/netflix) and simply see it for what it is.

I think that is very difficult. Watching movies at home is about comfort and zoning out (tied, I think, to early TV watching). So it’s a fight. We want comfort. I want comfort. But looking at “art” is not a comfortable experience; it wants us engaged in it; it demands an emotional investment.

The perfect film is both engaging and exciting but does not overwhelm us. It takes us into a world and involves us in an emotional experience and somehow changes us. It gives us the ability to see an intrinsic and undeniable truth about ourselves. Essentially it can be compared to any relationship we have; it is distant enough to give us a perspective and close enough to allow us an emotional response. Good film allows us the distance to observe and an emotional connection, that is the same as what two people need to live together. It doesn’t numb us or alienate. It allows us to bridge the gap between ourselves and the experience.

The movies that have stuck with me for years and still exert a pull when I think of them are the ones which really use the medium to create a “total” experience, a complete world which may or may not have a direct connection to the “real” world … I can still remember the feeling of walking out of the theatre after a matinee, sun shining, and feeling as if the world around me had changed in some way, or wasn’t quite as solid as it tried to seem. I used to feel energized after a movie, subtly changed … but I seldom get that feeling any more because I seldom feel completely enveloped by the experience, even the good ones.

Ironically, my capacity to appreciate this thing which has been so important to me, about which I have felt so passionate for so many years, has steadily diminished in direct proportion with my ability to possess movies as objects. Like the proverbial kid in a candy shop, I have perhaps consumed so much that I’m gradually losing my taste for the treats in front of me.

Comments

Nice work George

Who is this brilliant friend of yours

Astute clear and sheer brilliance

A shining light

Keep up the good work

I know what you mean, Megan. I too was surprised by his erudition!

Nicely done kids.

Kids? We’re grumpy old men!