Book Review: Showmen, Sell It Hot! by John McElwee

When I was working on my documentary about Winnipeg movie theatres, I spent hours and hours at the library going through old newspapers on microfilm, looking at movie ads. It was remarkable how strong the pull of those ads was – partly, no doubt, because of the associations with films which have long become a part of my stored memories. But I could also recall the power they had on me back when I read those papers the day they were published. Every week, I’d scan the entertainment section and see what was opening this Friday, what was held over and might demand another viewing …

by John McElwee

GoodKnight Books

It was those ads, along with the coming-soon posters in theatre lobbies and the trailers I saw before every feature, which quickened my pulse and made me impatient to buy a ticket. Back in those days, when movies opened more slowly and I’d read reviews weeks, even months, before a movie arrived in Winnipeg, the sight of an ad for an anticipated title gave me a thrill and I’d often be lining up for the first matinee showing on a Friday afternoon. Yet I don’t think I ever gave much thought to the effort which had preceded my encounters with these key moments of promotion. I took them for granted.

But the fact is, there was a vast and complex process geared towards triggering my excitement and interest. That process is the subject of a new book by John McElwee, who writes the fascinating Greenbriar Picture Shows blog which is devoted to the history of film promotion. Showmen, Sell It Hot! (GoodKnight Books, Pittsburgh) is an extension of that blog, a collection of 26 case studies running from Erich Von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives (1922: Universal proudly publicized its rush to chop the impossibly long movie — originally 32 reels — down to manageable size on a cross-country train equipped with multiple editing rooms, eventually delivering 14 reels just in time for the New York premiere, subsequently cut further down to 12) to Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967: McElwee argues that far from the accepted wisdom that Warners fumbled the release, it was actually smart marketing that opened it wide across the South before sending it into “more sophisticated” Northern urban centres). Being old-fashioned, I’m happy to be able to hold McElwee’s work in my hands rather than just scan it on my computer screen.

McElwee’s focus, lavishly illustrated with stills, posters and ads, is less on the corporate/studio end of promotion and more on the exhibitors’ end, the endless efforts made by theatre-owners to get audiences in seats. The movies after all are a business with a transient product which necessarily has to be sold and resold week after week, year in, year out. I think the book has given me a better understanding of the headaches of my friend Dave Barber who programs the Cinematheque here in Winnipeg, the constant balance he has to find between booking the titles he’s personally interested in and bringing in films which (hopefully) will make money … not always the same thing, unfortunately.

This perspective provides a different view of film history from the one we have which treats movies from a critical and creative angle. Many of the movies we now treasure as landmarks, classics, hugely influential, were actually a hard sell for the guys who were sweating out a living in cities and towns across the continent, where tastes and attitudes varied so widely that one theatre’s sophisticated success could easily produce nothing but the sound of crickets somewhere else.

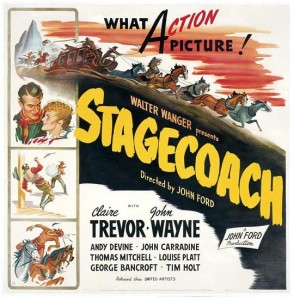

This approach produces some illuminating shifts in received wisdom. We tend to think of John Ford’s Stagecoach as the re-invention of the western and the start of something new in the genre, and yet it was just one of many westerns released in 1939 (including Dodge City, Union Pacific, The Oklahoma Kid) and not the most financially successful of them (Henry King’s Jesse James did twice the business). Our retrospective judgment of Ford’s movie is rooted more in our appreciation of the combination of psychological elements and the Monument Valley locations and our knowledge of who John Wayne subsequently became (at the time, Wayne was already a very successful star of westerns).

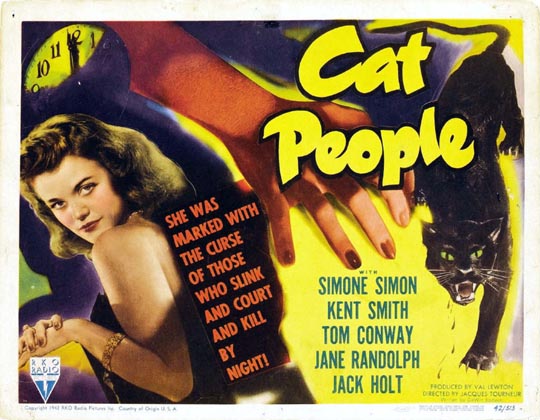

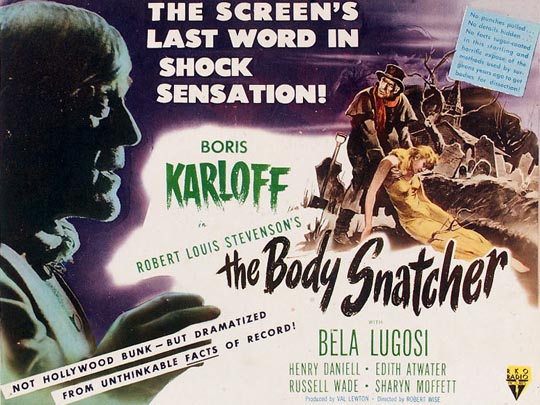

The films produced by Val Lewton at RKO are now legendary; here was a sophisticated man assigned to churn out low-budget programmers based on garish titles, who managed with his talented team of writers, directors and designers to create a group of subtle, elegant and atmospheric horrors. The first of these, Cat People, did very well for a small B picture, but each subsequent title crept up in cost above the initial $150,000 budget limit imposed on the producer and brought in smaller and smaller profits. As the financial picture grew darker, Lewton had Boris Karloff imposed on him by the powers in the front office. The first Lewton-Karloff film, The Body Snatcher, did the best business since I Walked With A Zombie, but its production costs had been much higher, so it made less profit. The final two Lewton horrors cost even more, and the last, Bedlam, actually lost money. As films, those nine small RKO titles are now much-loved; when they were first made, they struggled to attract sufficiently large audiences to turn a profit – although they did eventually bring a bit more money back to RKO through subsequent re-releases – and frustrated theatre owners looked at them and didn’t see the subtlety we now appreciate, just a lack of socko scares that would entice crowds into their empty theatres.

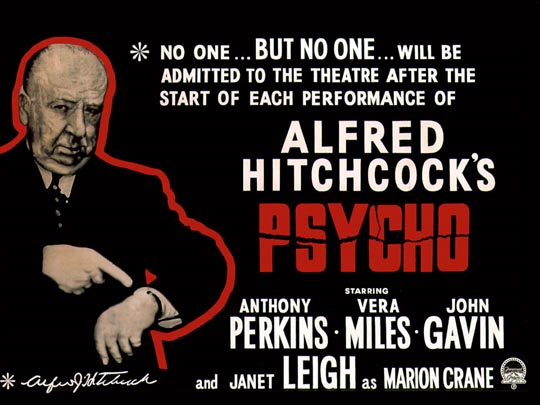

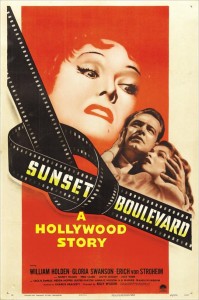

McElwee’s choice of cases is consistently interesting, from The Wizard of Oz and Citizen Kane (both expensive films which stumbled on first release) to oddities like Leo McCarey’s commie-baiting My Son John (intended as a Hitchcockian “suspense of ideas”, crippled by the death of its star before shooting finished, and loudly supported by the anti-Red American Legion) to the back-to-back success/failure of the Billy Wilder duo Sunset Boulevard and Ace In the Hole to Hitchcock’s radical campaign for Psycho and the successful ’50s re-release of Little Caesar and Public Enemy as a double bill.

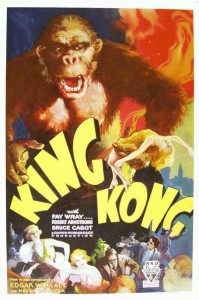

In fact, in the pre-television, pre-home video era, it seems that many movies were quite regularly re-released to theatres, often with as much promotional ballyhoo as new features. King Kong was a perennial earner for RKO and Jesse James ran theatrically on and off into the ’70s.

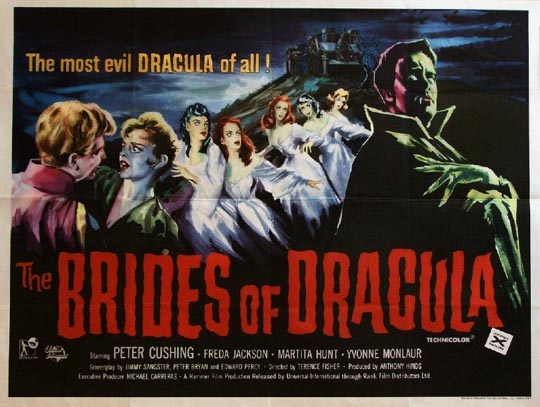

Some of McElwee’s stories are really surprising. Who knew, for instance, that Hammer’s Brides of Dracula had its world premiere at the Malco Theater in Memphis, Tennessee, on June 3, 1960? Certainly not IMDb, which lists the U.S. release date as September 5, with earlier releases in Britain and Japan. But beyond the oddity of a Hammer Gothic opening in Memphis, what’s surprising is that it was a huge success in a 3000-seat theatre, thanks to massive promotional efforts overseen by a colourful character named A-Mike Vogel. (“’Find a newly married couple willing to spend their wedding night in the graveyard!’ fairly captured the spirit of A-Mike’s strategy.”)

The book is nicely designed, packed with colour and black-and-white illustrations, but I have to confess that there are times when McElwee’s writing style gave me pause. His prose is oddly compressed, his meaning occasionally slightly obscure, almost as if Yoda were writing for Daily Variety (on the Little Caesar/Public Enemy re-release: “Warners now had wicket votes enough to proceed with nation-wide rollout, confident that the expense of fresh campaigning would be more than rewarded. Found money this was, but adding to it meant fresh paper, trailers, and new prints for saturation play.”) … but even this adds to the book’s personality and charm. This is not an academic study, but the passionate work of a very well-informed enthusiast.

Showmen, Sell It Hot! is an entertaining read, but it also has the power to alter the way we look at the movies we’ve become so familiar with as our access has increased exponentially in the past few decades. Reading these stories of the often Herculean struggles to get movies seen, it seems remarkable that so many of our now-favourites managed to survive and eventually prosper; but McElwee also inspires a degree of sympathy for the men (yes, they were mostly men) who we might have been inclined to dismiss as Philistines for their lack of appreciation when offered a “classic” and who instead might opt for something less cinematically significant but more immediately crowd-pleasing.

Comments